The Dutch national archives are showcasing a unique set of letters sent by the leader of the first organized slave revolt on the American continent to a colonial governor, in which the newly free man proposed to share the land.

The offer from the man known as Cuffy, from Kofi – meaning “born on Friday” – is said to provide new insight into attempts to resist the brutal regimes of the colonial period, often overlooked in histories of enslaved people.

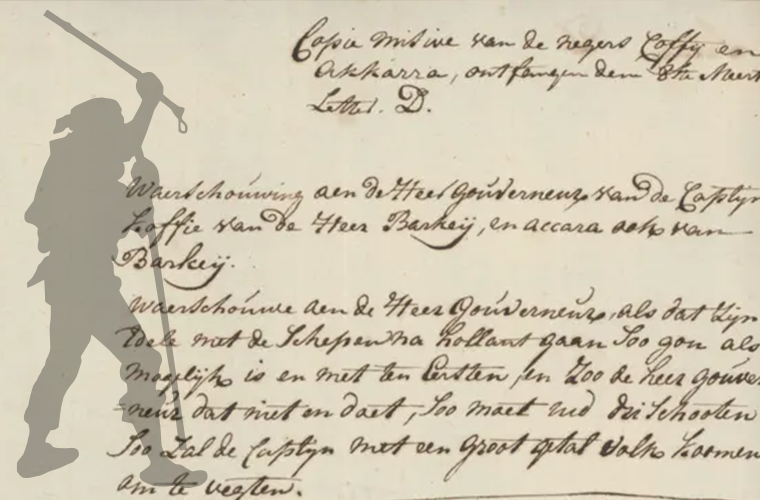

“We will give Your Excellency half of Berbice, and all the negroes will retreat high up the rivers, but don’t think they will remain slaves. The negroes that Your Excellency has on his ships – they can remain slaves,” the rebel leader wrote to the local governor, Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim.

Berbice, now part of Guyana, was a Dutch colony for two centuries, and in 1763 approximately 350 white Europeans were keeping an estimated 4,000 slaves on coffee, cotton, and sugar plantations in increasingly barbaric conditions, even by the cruel standards of the time.

Cuffy had probably been brought there by traffickers after being bought as a child in West Africa. On the morning of 23 February 1763, a group of around 70 men and women on one colonial plantation overpowered their captors and encouraged the neighboring slaves to join them, leading to a rebellion of about 3,000 people.

The colonialists fled as the revolt grew but around 40 men and 20 women and children found themselves surrounded by 500 formerly enslaved people after taking refuge in a house on one of the plantations. The roof was set on fire and escapers were shot, according to the writer and historian Karin Amatmoekrim.

Van Hoogenheim burned down the colony’s Fort Nassau to avoid it being taken into rebel hands, leading Cuffy, who had taken leadership of the rebellion, to appoint himself as the new governor of Berbice.

But Cuffy informed Van Hoogenheim that he wanted to end the violence, which he said had been provoked by the cruelty of a particular group of plantation owners. It is this correspondence that now features in the Rebellion and Freedom exhibition, albeit only online for now owing to coronavirus regulations.

“Cuffy, Governor of the Negroes of Berbice, and Captain Akara send greetings and inform Your Excellency that they are not seeking war. But if Your Excellency wants war, the Negroes are willing to do so,” Cuffy wrote. “The Governor of Berbice asks Your Excellency to come and speak to him; Do not be afraid. But if you don’t come, we’ll fight on until there is no Christian left in Berbice.”

According to Amatmoekrim, there was skepticism among the other newly freed people at this attempt to find terms with the colonialists, apparently in part born out of the distrust felt by some about Cuffy, who was one of the few “house slaves”, working often in close proximity to the plantation owners.

Van Hoogenheim waited it out as Cuffy was challenged by a new leader, Atta, leading to a showdown between the two camps of supporters. Cuffy lost out and subsequently killed himself.

A few months later 600 Dutch soldiers docked at Berbice port, leading to the colony’s recapture by the summer of 1764 and savage repercussions. Around 1,800 rebels died, with 24 burned alive, according to Amatmoekrim.

“The history of the Berbice uprising is important as it shows that our colonial past is laced with histories of revolt and resistance,” she said. Cuffy’s story, among others, she said, highlighted “the kind of heroism that has not easily penetrated the history books: black, enslaved, and fighting to the bitter end for their own freedom.”