By Mehrsa Baradaran

The Constitution is riddled with compromises made between the North and South over the issue of slavery — the Electoral College, the three-fifths clause — but paper currency was too contentious an issue for the framers, so it was left out entirely. Thomas Jefferson, like many Southerners, believed that a national currency would make the federal government too powerful and would also favor the Northern trade-based economy over the plantation economy. So, for much of its first century, the United States was without a national bank or a uniform currency, leaving its economy prone to crisis, bank runs and instability.

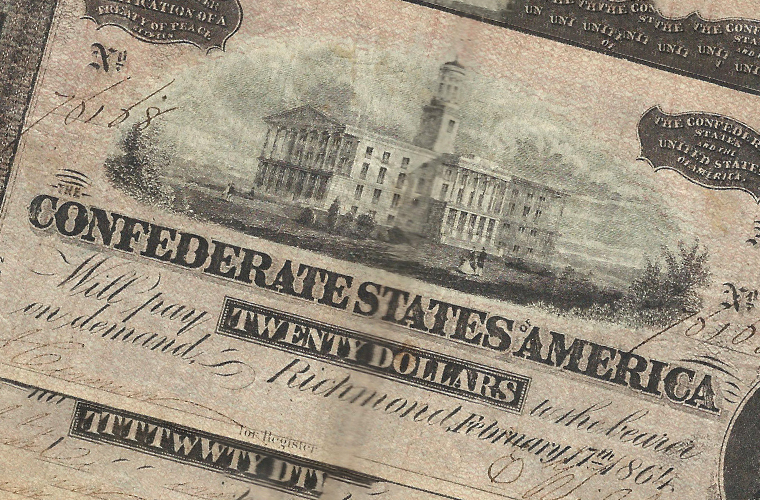

At the height of the war, Lincoln understood that he could not feed the troops without more money, so he issued a national currency, backed by the full faith and credit of the United States Treasury — but not by gold. (These bills were known derisively as “greenbacks,” a word that has lived on.) The South had a patchwork currency that was backed by the holdings of private banks — the same banks that helped finance the entire Southern economy, from the plantations to the people enslaved on them. Some Confederate bills even had depictions of enslaved people on their backs.

In a sense, the war over slavery was also a war over the future of the economy and the essentiality of value. By issuing fiat currency, Lincoln bet the future on the elasticity of value. This was the United States’ first formal experiment with fiat money, and it was a resounding success. The currency was accepted by national and international creditors — such as private creditors from London, Amsterdam, and Paris — and funded the feeding and provisioning of Union troops. In turn, the success of the Union Army fortified the new currency. Lincoln assured critics that the move would be temporary, but leaders who followed him eventually made it permanent — first Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression and then, formally, Richard Nixon in 1971.