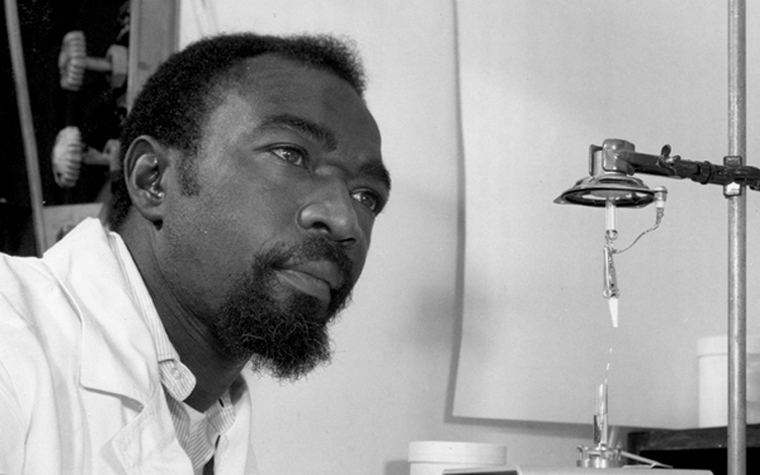

James A. Harris was an essential member of the team at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory that produced two previously unknown elements—Element 105, created in 1969, and Element 105, detected in 1970. The first African American scientist to play a key role in the search for new elements, he was once described by a writer for Ebony magazine as a “hip, scientific soul brother.”

Harris was born in Waco, Texas, in 1932 and raised by his mother after his parents divorced. He left Waco to attend high school in Oakland, California but returned to Texas to study science at Huston-Tillotson College in Austin. After earning a B.S. in chemistry in 1953 and serving in the Army, he confronted the difficulties of finding a job as a black scientist in the Jim Crow era.

“I could write a book about my job-hunting experiences,” he said. Receptionists for some potential employers were incredulous that he was applying for a job in chemistry rather than as a janitor. A number of interviewers couldn’t hide their shock when they met him. But he persisted in his search and landed employment in 1955 at Tracerlab, a commercial research laboratory in Richmond, California. Five years later he accepted a position at the Lawrence Radiation Lab (later renamed Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory), a facility of the Department of Energy operated by the University of California.

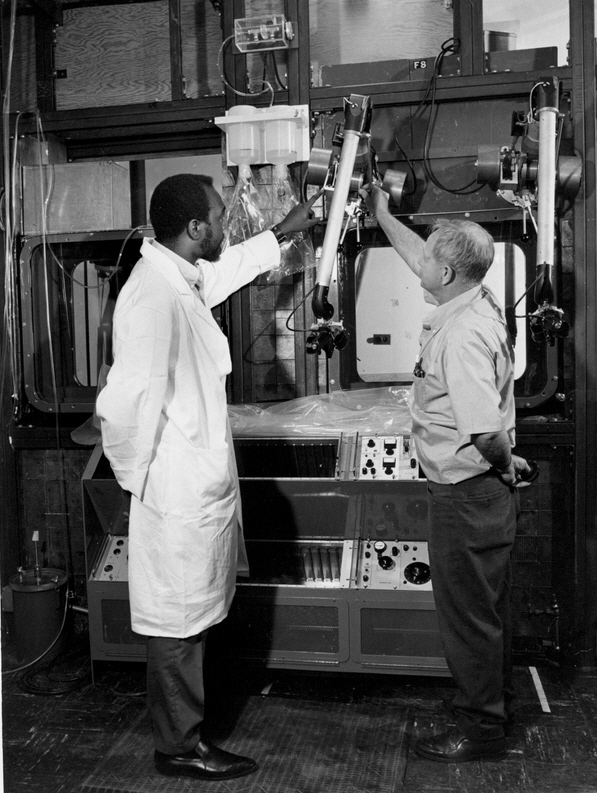

There he worked in the Nuclear Chemistry Division as head of the Heavy Isotopes Production Group. His responsibility was to purify and prepare the atomic target materials that would be bombarded with carbon, nitrogen, or other atoms in an accelerator in an effort to create new elements. The purification process was extremely difficult, and Harris was highly regarded for his meticulous work in producing targets of superb quality.

After the discoveries of Elements 104 and 105—named, respectively, Rutherfordium and Hahnium, after atomic pioneers Ernest Rutherford and George Hahn—Harris’s team continued to search for other super-heavy elements that might prove beneficial to medicine, energy production, or other purposes.

Harris extended his scientific training with graduate courses in chemistry and physics and received an honorary doctorate from Houston-Tillotson College for his contributions to the discovery of new elements. He devoted much of his free time to recruiting and supporting young African American scientists and engineers, often visiting universities in other states. He also worked with elementary school students, particularly in underrepresented communities, to encourage their interest in science. These efforts brought him many awards from civic and professional organizations, including the Urban League and the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers.

Married and the father of five children, Harris was devoted to his family and balanced his professional work with other pastimes, including golf, travel, and community activities.