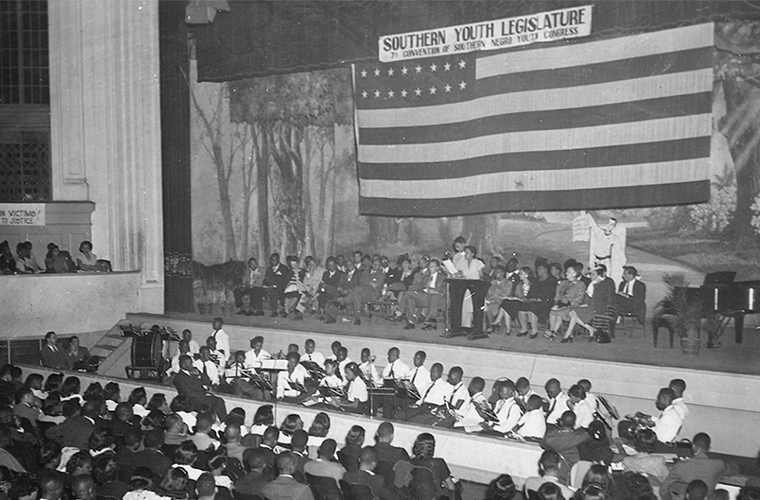

Founded in 1937, the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) was a civil rights organization that worked to empower southern black people to fight for their rights and looked with hope to interracial working-class coalitions as the key to undermining the southern caste system.

The SNYC had its roots in both the National Negro Congress (NNC) and the leftist student movement of the 1930s. In 1936, the NNC convened to address the economic problems and discrimination faced by African Americans, particularly in New Deal programs. Although the vast majority of NNC delegates were from northern communities, younger delegates acknowledged that the problems facing southern black people were especially acute and inseparable from the problems northern African Americans faced. Many of these younger delegates were also active in leftist student organizations, such as the American Student Union and the American Youth Congress.

In fact, the student movement was an important training ground for SNYC leaders like Edward Strong, James E. Jackson, Jr., and Louis Burnham. These student activists resolved that the battle against discrimination and segregation had to be waged by a black-led southern organization, and they spearheaded a conference of young black southerners.

Over five hundred delegates attended the founding conference of the SNYC, held in Richmond, Virginia, in February 1937. The conference delegates issued a broad proclamation, demanding equal educational and employment opportunities, the right to organize unions, the right to vote, and an end to lynching and segregation. The delegates also reached out to southern white youth and to workers, especially those in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which advocated organizing workers on an interracial basis.

At the close of the conference, the delegates created a permanent organization, headquartered in Richmond. The SNYC initiated its work in April 1937, when it organized black workers on strike at the Carrington and Michaux tobacco factory. Their efforts resulted in an independent union, called the Tobacco Stemmers’ and Laborers’ Union (TSLU); the TSLU succeeded in gaining an eight-hour day and forty-hour workweek, along with a wage increase. The SNYC went on to organize other TSLU locals among black workers in other tobacco factories.

The SNYC exemplified the inclusiveness of Popular Front politics during the Great Depression by reaching out to all members of the black community and to political radicals, as well as to the white working class. SNYC moved its headquarters to Birmingham, Alabama, in 1940 and was active until 1949.