The Black Star Line was a historic shipping company established by Marcus Garvey in 1919. The company was founded with the intention of promoting black economic independence and providing a means of transportation for goods and people between the United States, the Caribbean, and Africa. Marcus Garvey, a prominent leader in the Pan-African movement, saw the Black Star Line as a way to unite people of African descent and create opportunities for economic empowerment. The company’s name, “Black Star,” was inspired by the flag of Ethiopia, which featured a black star in its center and was seen as a symbol of African unity and pride.

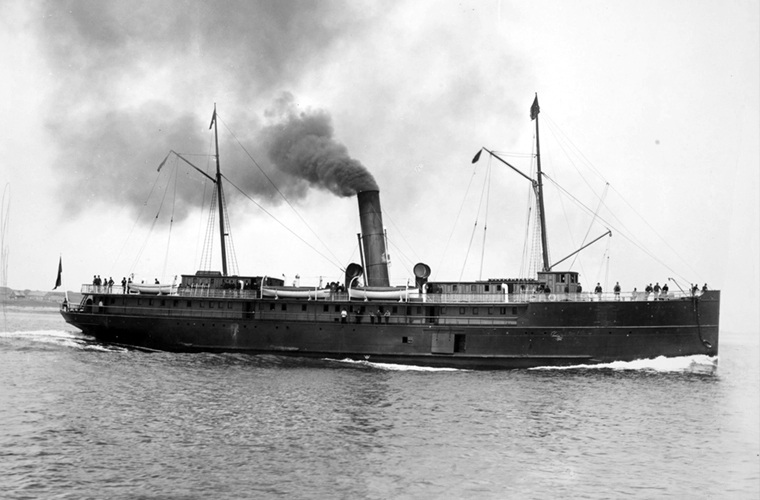

The Black Star Line’s inaugural voyage took place on November 17, 1919, with the sailing of the SS Yarmouth from New York to the Caribbean. The company initially faced challenges in acquiring ships and securing funding, but eventually acquired several vessels to expand its operations. The Black Star Line aimed to provide affordable and reliable transportation for goods and passengers, particularly those of African descent. The company also sought to create employment opportunities for black workers in the shipping industry and to foster trade between African nations and the diaspora.

Despite its noble intentions, the Black Star Line faced numerous obstacles, including financial difficulties, legal disputes, and allegations of mismanagement. The company struggled to maintain its operations and ultimately ceased its shipping activities in the mid-1920s. While the Black Star Line’s impact was limited in terms of its commercial success, its significance lies in its symbolic importance as a manifestation of black pride, self-determination, and economic empowerment. The company’s legacy continues to inspire movements for social and economic justice within the African diaspora.

In conclusion, the Black Star Line was a pioneering effort to promote black economic independence and foster connections between people of African descent across the globe. Despite its challenges and ultimate demise, the company remains a symbol of resilience and determination in the pursuit of equality and empowerment.