The Town Destroyed to Make Way for Central Park: Seneca Village, N.Y. — Seneca Village was founded in 1825 when Epiphany Davis and Andrew Williams became the first African-Americans to buy land in the area. Trustees of the AME Zion Church then purchased eight plots of land close by. By 1829, nine homes had been built. The dwellings ranged from one-room houses to three-story houses made of wood and brick. The town also featured three churches and a schoolhouse. According to the Central Park Conservancy, an 1855 census showed 250 residents living in Seneca Village, with 70 homes built. After a history of just 32 years, the end of the town came when the New York State legislature used eminent domain to seize the occupied land and build what is now Central Park.

The Town Destroyed to Make Way for Central Park: Seneca Village, N.Y. — Seneca Village was founded in 1825 when Epiphany Davis and Andrew Williams became the first African-Americans to buy land in the area. Trustees of the AME Zion Church then purchased eight plots of land close by. By 1829, nine homes had been built. The dwellings ranged from one-room houses to three-story houses made of wood and brick. The town also featured three churches and a schoolhouse. According to the Central Park Conservancy, an 1855 census showed 250 residents living in Seneca Village, with 70 homes built. After a history of just 32 years, the end of the town came when the New York State legislature used eminent domain to seize the occupied land and build what is now Central Park.

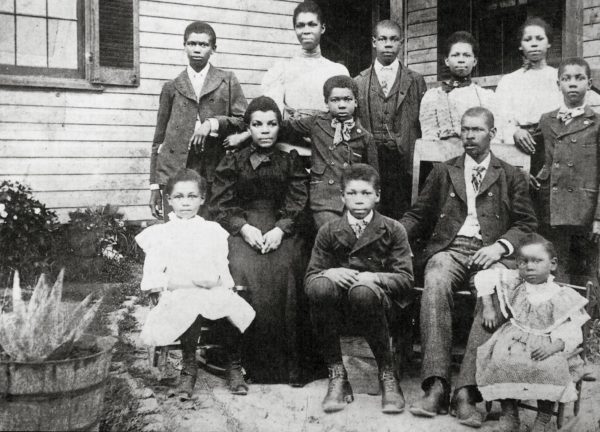

Early settlers of North Brentwood, Maryland.

Early settlers of North Brentwood, Maryland.

A Town of Firsts: North Brentwood, Maryland — Incorporated in 1924, North Brentwood was Prince George’s County’s first African-American municipality. It was developed from farmland owned by Wallace A. Bartlett, a white commander of the 19th infantry of the U.S. Colored Troops in Brazos and Brownsville, Texas during the Civil War. He created the Holladay Land and Improvement Division in 1887 and sold pieces of land in the floodplains to his fellow soldiers, formerly enslaved Africans, and Black families. North Brentwood became a politically and economically sufficient town, boasting its own government, businesses, and religious institutions. It was home to 800 people by 1930, according to the North Brentwood Directory. The city was occasionally flooded after heavy rains, but a levee was finally built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1950s. It still exists today with a population of 517, according to a 2010 census.

Hunterfly Roadhouses with St. Mary’s Hospital in the background, the 1920s.

Hunterfly Roadhouses with St. Mary’s Hospital in the background, the 1920s.

The Town of Refuge: Weeksville, New York — Weeksville was formed in 1838 by a Black freedman named James Weeks after he purchased a large amount of land from Henry C. Thompson, another free Black man. The town, located in what is now the Bedford-Stuyvesant region of Brooklyn, New York, became the second-largest community for free Blacks in the pre-Civil War era. It also became a safe haven for Blacks fleeing slavery in the South and a refuge for northern Blacks trying to get away from racial turmoil and violence in other parts of the country. Weeksville was known for employing Black professionals and allowed them to hone their skills and build clientele. Schools, churches, a home for the elderly, and an orphanage were set up in the town as well. It even had its own newspaper called The Freedman’s Torchlight, which was one of the nation’s first African-American newspapers, according to BlackPast.org. By 1900, Weeksville was home to more than 500 families made up of doctors, teachers, preachers, and other professionals. The community was engulfed by the rapid growth of Brooklyn in the 1930s however, and almost forgotten. Plans were made to preserve the last of the 19th-century cottages, known as the Hunterfly Road Houses, which still stand today. The town was declared a landmark in 1971.

The thriving Greenwood District

The thriving Greenwood District

The Black Wallstreet: Greenwood, Oklahoma. — Oklahoma’s Greenwood District was one of the most affluent African-American towns in the U.S. It boasted many successful businesses and a sprawling residential area. However, in June of 1921, it was burned to the ground by white rioters. The Tulsa Race Riot began when a Black man named Dick Rowland rode in the elevator of the Drexel Building with a woman named Sarah Page. Exaggerated accounts of what happened traveled from person to person, eventually making its way to the white community. Rowland was then arrested and questioned. On June 21, 1921, Black Tulsa was looted and burned by whites, according to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum. Thirty-five city blocks were destroyed and 300 people lost their lives that day.

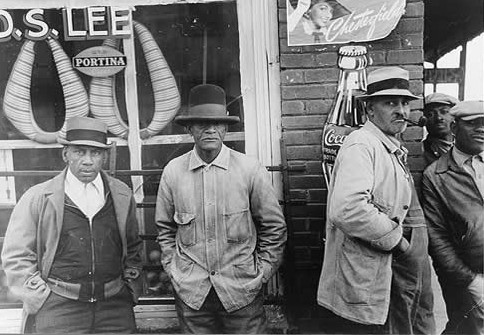

Mound Bayou Residents in Front of Store, the Late 1930s

Mound Bayou Residents in Front of Store, the Late 1930s

The Land of Promise: Mound Bayou, Mississippi — Mound Bayou was an all-Black town located in the Yazoo Delta of Northwest Mississippi. Established in 1887 by Isaiah Montgomery and 12 other pioneers, the town was considered a new “land of promise” for Black Americans. According to BlackPast.org, an online reference guide to African-American history, this promise included “self-help, race pride, economic opportunity, and social justice.” The community was also self-segregated, which limited interaction with whites until integration was an option. Mound Bayou had a post office, six churches, a bank, and countless public and private schools. Through its newspaper, The Demonstrator, the town pushed the importance of education. The community continued to thrive and boasted a population of 8,000 by 1911. Unfortunately, The Great Migration period from 1915 to 1930 caused a sharp decline in the populace. Yet, the town still exists today.

The original St. Joseph Catholic Church

The original St. Joseph Catholic Church

The City on the Move: Glenarden, Maryland — Glenarden got its start in 1910 when a Black man named W. R. Smith purchased multiple tracts of land and founded a residential community of about 15 people. The small town, built near the Washington, Baltimore, and Annapolis Electric Railway, flourished over the next three decades and developed into a middle-class suburban neighborhood. A two-room schoolhouse and the St. Joseph’s Catholic Church were constructed in 1922. The community then petitioned the State Legislature for incorporation as the Town of Glenarden, according to the City of Glenarden’s official website. The charter was approved on March 30, 1939, making it the third predominately African-American organized town in the state of Maryland. By the late 1940s, there were 51 houses in the area, along with a post office, barbershops, two restaurants, a dry cleaner, and a gas station. The name of the community was also changed from the Town of Glenarden to the City of Glenarden in April 1994.

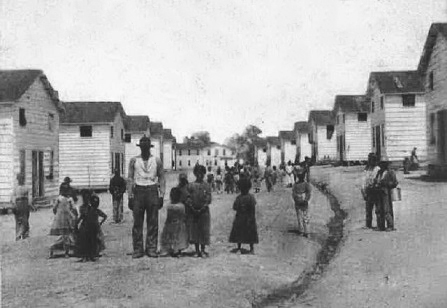

A few residents of Freedman’s Village

A few residents of Freedman’s Village

A Place for Free Men, Women, and Children: Freedman’s Village, Virginia — The U.S. government established the Freedman’s Village in May of 1863. The community was founded to address the increased number of Black Americans who escaped slavery in the South during the Civil War. The mission of the Freedman’s Village was to “house, train and educate freedmen, women, and their children.” It also provided food, job training, church services, and medical care. The village, located in what is now Arlington Cemetery, was operated by the Freedman’s Bureau for the majority of its existence. A school was opened as well, initially enrolling just 150 students; enrollment peaked at 900 students. Although the village was created to provide temporary refuge to Blacks who escaped bondage, the community continued to grow and operated for over 30 years. The U.S. Supreme Court closed Freedman’s Village, however, in 1882, and allotted the land for the military.

David Profitt house, a typical house in Blackdom, New Mexico

David Profitt house, a typical house in Blackdom, New Mexico

The Black Ghost Town: Blackdom, New Mexico — The modest town of Blackdom was founded by Frank Boyer and Ella Louise McGruder. According to the City of Albuquerque’s official website, it was the first all-Black settlement in the New Mexico Territory. By 1908, Blackdom was home to approximately 300 residents and 25 families. Altogether, these families owned about 15,000 acres of land. The town was complete with a blacksmith’s shop, post office, hotel, and the Blackdom Baptist Church, which doubled as a schoolhouse. Cotton, onions, sugar beets, and cantaloupe were among many crops grown on the land. Over time, however, worms ruined the crop and the wells dried up, leading to the demise of the town. The Boyers relocated to Pacheco and then to Vado, N.M. About 220 members of the Boyer family reside in the Vado area today.

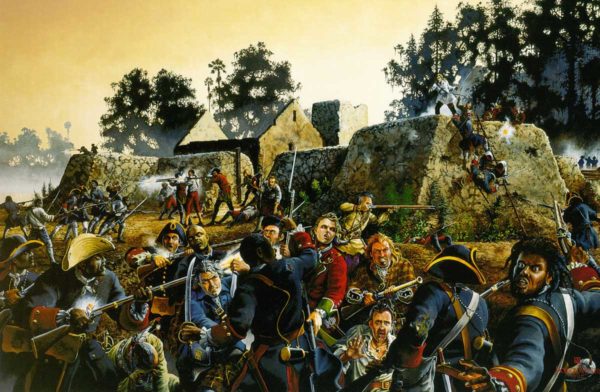

The Fort Mose militia and Spanish soldiers defended St. Augustine and the surrounding area when James Olgethorpe attacked them in 1740.

The Fort Mose militia and Spanish soldiers defended St. Augustine and the surrounding area when James Olgethorpe attacked them in 1740.

The ‘Emancipation Proclamation of the South: Fort Mose, Florida —

Tucked in the marshes of St. Augustine lies the site of the first free community of enslaved Africans. Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, better known as Fort Mose (pronounced Moh-say), was established in 1738. Enslaved people from British colonies followed the original Underground Railroad, which didn’t lead north at the time, but south to the Spanish colony of Florida. They were then given their freedom as long as they pledged their allegiance to the King of Spain and converted to Roman Catholicism.

A group of people stands outside a Boley home.

A group of people stands outside a Boley home.

The Crown Jewel: Boley, Oklahoma — The community of Boley was located in the Creek Nation of Indian Territory. Founded in 1903, it was the first of 30 towns established in the West following the Civil War. Blacks arrived in the area as enslaved peoples of the Native Americans, who had been displaced and forced to move to Oklahoma via the “Trail of Tears.” Among the community’s founders were Lake Moore, a white lawyer; John Boley, a white supervisor of the Fort Smith and Western Railroad; and Thomas M. Hayes, a Black farmer and business owner from Texas. The trio also worked alongside James Barnett, a Cherokee Freedman, to purchase the land from Barnett’s daughter. Boley was home to various businesses, schools, banks, fraternal clubs, and churches. It also had a train depot, post office, power plant, and telephone company. The beginning of Oklahoma statehood in 1907 also meant the beginning of segregation and disenfranchisement of the town’s citizens. Political unrest and economic hardship eventually led to a dwindling population. The city remains mostly Black and is home to the families of the town’s original settlers.