The Unsung African American Inventor Who Revolutionized Laundry

In the annals of American innovation, few stories capture the intersection of ingenuity, racial injustice, and quiet resilience more vividly than that of Ellen F. Eglin. Born in the mid-19th century amid the shadows of slavery’s aftermath, Eglin emerged as a trailblazing African American inventor whose creation—a practical clothes wringer—transformed household chores for generations. Yet, her legacy is one of bittersweet irony: while her device brought fortune to others, Eglin herself received a mere $18 for her patent, a stark reminder of the barriers Black women faced in pursuing their dreams.

Ellen F. Eglin was born in 1849 in Washington, D.C., a city pulsing with the complexities of post-Civil War reconstruction. Details of her childhood remain sparse, reflecting the limited records kept for Black Americans during that era. Growing up in a time when opportunities for education and economic independence were scarce for her community, Eglin likely drew from the everyday rigors of domestic life to fuel her inventive spirit. By her early adulthood, she had taken on roles that showcased her diligence and adaptability: working as a housekeeper for the family of Timothy Nooning, a prominent figure in the capital, and later as a clerk in a local census office. These positions, while modest, provided her with the financial stability—and perhaps the inspiration—to tinker with solutions to the monotonous labor that defined women’s work.

Washington, D.C., in the late 1800s, was a hub of emerging federal bureaucracy and social change, but it was also a place where racial prejudice lingered like a stubborn stain. As a Black woman navigating these waters, Eglin’s path was one of quiet determination. She shared her home with her brother Charles, a Union Navy veteran and teamster whose service in the Civil War symbolized the sacrifices of countless African Americans in the fight for freedom. Charles’s death in 1896 left a void, but Eglin pressed on, her inventive pursuits becoming a beacon of personal agency.

The Breakthrough Invention: A Wringer for the Weary

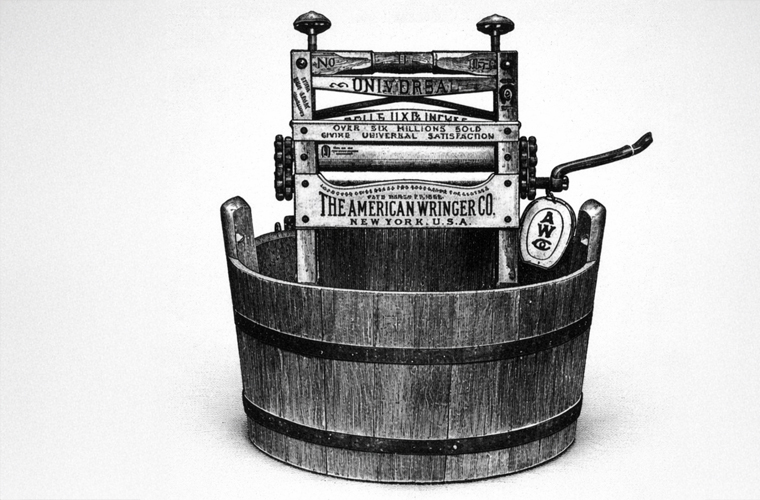

By 1888, Eglin had turned her gaze to one of the most tedious household tasks: wringing water from freshly washed clothes. Hand-squeezing laundry was backbreaking, time-consuming, and prone to injury, especially in an age without modern appliances. Eglin’s solution was elegant in its simplicity—a mechanical clothes wringer featuring two adjustable rollers that squeezed garments dry as they passed through, mimicking the human hand but with far greater efficiency.

What set her design apart were the thoughtful innovations: a system of spur-gearing allowed users to vary the rollers’ speed, accommodating everything from delicate silks to heavy linens with minimal effort. Even a child could operate it, thanks to the low power required and ergonomic crank mechanism connected to gear wheels of different sizes. This wasn’t just a gadget; it was a liberator for homemakers, reducing drying time and easing the physical toll of laundry day. Eglin’s wringer addressed a universal pain point, yet its path to market would expose the era’s deep-seated biases.

On August 15, 1888, Eglin filed for and received U.S. Patent No. 397,276 for her “Washing-Machine Roller,” marking her as one of the few Black women to secure a patent in the 19th century. But the celebration was short-lived. Fearing rejection in a racially divided marketplace, she made a heartbreaking decision: to sell the rights to her invention for a paltry $18 (roughly $600 in today’s dollars) to an anonymous white agent. In a poignant interview later published in *Woman Inventor* magazine, Eglin explained her rationale: “You know I am black, and if it were known that a Negro woman patented the invention, white ladies would not buy the wringer. I was afraid to be known because of my color in having it introduced into the market—that is the only reason.”

The agent, whose identity remains elusive, reportedly passed the patent to Cyrenus Wheeler Jr., a white inventor and owner of the Troy Iron Works, a major manufacturer of wringers. Wheeler refined and marketed it under his name, turning it into a commercial hit that generated substantial wealth—none of which trickled back to Eglin. Her device, stripped of her credit, became a staple in American homes, quietly easing the burdens of laundry for countless women while Eglin faded into obscurity.

Later Years and Unfulfilled Dreams

Undeterred, Eglin channeled her energies into new projects. In the early 1890s, she developed another invention—rumored to be an improvement on household tools—but chose not to patent it under her own name, perhaps scarred by her prior experience. She even planned to showcase it at the Women’s International Industrial Inventors Congress, a gathering of female innovators, but ultimately did not attend, and the device’s details were lost to time.

Eglin continued her steady climb in government service, securing a position as a charwoman (janitor) in the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Census Office by 1890. This role, while unglamorous, offered a measure of security in a city where Black women often faced exploitation. She resided at 1929 11th Street, N.W., a modest address that anchored her final decades. Eglin last appeared in Washington city directories in 1916, passing away around 1915 at the age of 66.

A Legacy of Innovation Amid Invisibility

Ellen Eglin’s story is a microcosm of the African American experience in Gilded Age America: brilliance overshadowed by bigotry, contributions claimed by others, and resilience in the face of erasure. Though she profited little from her wringer, her invention’s enduring utility—evolving into the modern washing machine’s spin cycle—speaks to her foresight. Today, she is celebrated during Black History Month and Women’s History Month as a symbol of overlooked genius, her name revived through scholarly works, documentaries, and exhibits at institutions like the Smithsonian.

In an era when Black inventors like Eglin were often forced to choose between recognition and reward, she opted for impact over acclaim. As we reflect on her life, Eglin’s words echo as a call to equity: true progress demands not just invention, but justice for those who create it. Her wringer may have squeezed water from clothes, but it was systemic racism that wrung opportunity from her grasp—a wrong history is only beginning to right.