As July lengthens, the flood of ads for TV series, films, and events commemorating the 50th anniversary of July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 moon landing has hit a high mark. Through grainy footage of slow-motion rocket launches and high-definition interviews, they tell a familiar but thrilling tale of America’s nascent steps off the planet.

Most look crisp and compelling, offering a vital history lesson during a time when America could desperately use something to unite around and celebrate.

But most don’t have Ed Dwight Jr.

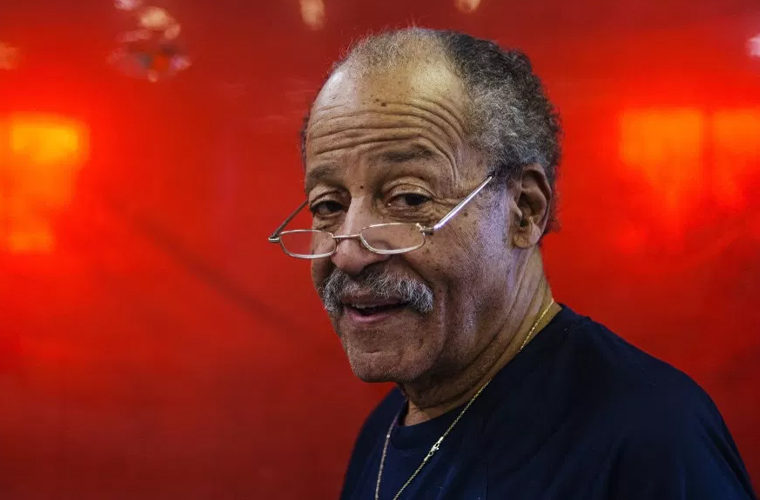

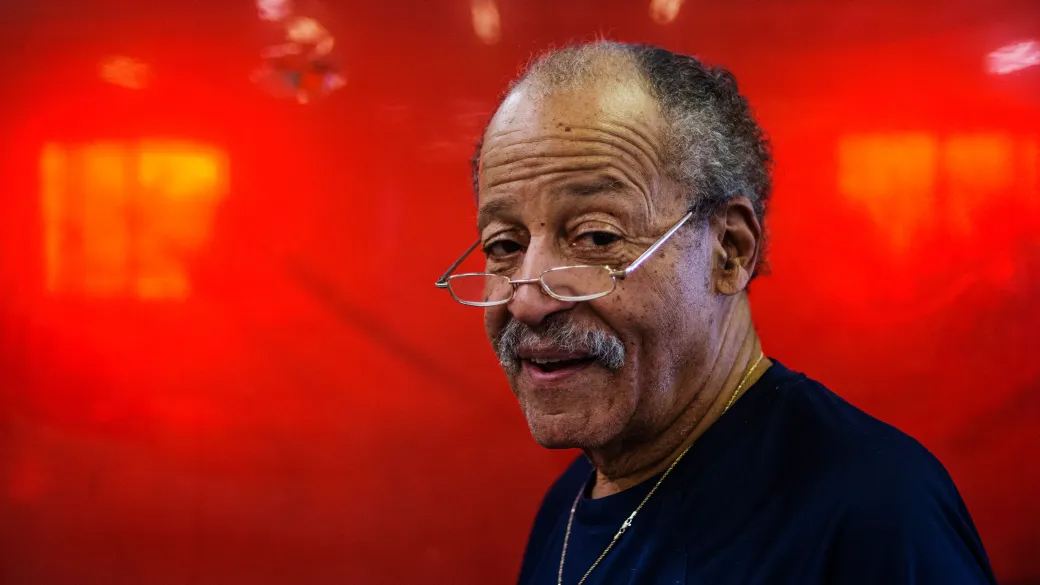

“My first thought was, ‘Why the hell are they including me in this?’ ” Dwight, a Denver-based sculptor, said of the new PBS series “Chasing the Moon,” which premieres July 8-10 on Rocky Mountain PBS, KRMA-Channel 6. “But then I realized it had everything to do with what led up to it.”

Dwight has worked for decades as a sculptor, earning an international reputation with more than one hundred public dedications and thousands of private commissions and sales. His work can be seen at national parks, monuments, sports stadiums, and galleries in Denver and around the world, having depicted everyone from President Barack Obama to slain Denver Broncos player Darrent Williams and America’s oft-forgotten black pioneers.

But the 85-year-old’s artistic success obscures an important piece of aerospace history.

In 1961, Dwight was hand-picked by President John F. Kennedy’s administration to become the first-ever African-American astronaut — a sign of both Kennedy’s progressive values and his savvy image-tending. At the time, the U.S. was locked in a life-or-death chess match with the Soviet Union, and each move created international ripples of fear, anticipation and — when it came to the rapidly developing, all-or-nothing space program — jealousy and competition.

A Kansas City native, Dwight was a gifted aeronautical engineer who was fast rising through the Air Force ranks, tapped by his superiors as he’d been for the Pentagon’s upper-management fast-track. But when Dwight was invited to begin astronaut training at Edwards Air Force Base in southern California, under the guidance of legendary pilot Chuck Yaeger (the first man ever to break the sound barrier), he wavered.

“Dr. (Martin Luther) King was riding high at the time, and I was told, ‘It’s a possibility to be a credit to your race,’ ” Dwight said from his 30,000-square-foot art studio at 3824 Dahlia St. last week. “They said, ‘We can show the world that the black folks can have a scientific mind and make scientific contributions as well,’ and it was very romantic to hear stuff like that. I thought 30 or 40 of these letters were sent out to 30 or 40 black guys, and then maybe they picked the best ones. I did not realize they had zeroed in on me.”

Dwight felt an immediate backlash as he appeared on national magazine covers, TV news broadcasts, and radio programs. Racist politicians, reporters, and citizens questioned his physical and mental fitness, skeptical that a black man had what it took to make it to space.

“These guys — I call them the forces of darkness — came in with all kinds of medical and intellectual questions about black people’s physiology and intelligence,” he said. “They did studies and presented them to the White House and Congress saying my capabilities weren’t even in the ballpark. It was incredibly controversial and political.”

Doubtful, too, were some of Dwight’s Air Force colleagues who saw his selection as symbolic rather than substantive.

” ‘Forget it,’ ” he remembers them telling him at the time. ” ‘You’re a junior officer in a cubicle handling intelligence briefs on whether or not to bomb China or Russia. You’re an operations guy. These are R&D guys. They’re not going to like this little black shrimp (Dwight is 5-foot-four-inches tall) coming down there and being put in the middle of their party.’ ”

Starting in 1962, Dwight trained on the ground and in the air with Yaeger and others, flying experimental aircraft and undergoing a battery of tests designed to establish his overall demeanor, problem-solving skills, and knowledge. He relished the opportunity and delighted in the access to cutting-edge technology. But when Kennedy was assassinated a year later, his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, hand-picked a different African-American pilot (Robert Henry Lawrence, Jr.) to become the first black astronaut. That, along with Dwight’s allegiance to Kennedy and disillusionment with national politics, grounded his enthusiasm for his military career.

Dwight eventually left the Air Force in 1966. And Lawrence, who was selected as an astronaut for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program, never made it to space. He was killed in a plane crash in 1967, according to Popular Mechanics.

The naturally industrious Dwight gravitated toward a technical career in the private sector, moving to Denver in 1966 to work for IBM as an engineer and, eventually, a self-made restaurateur.

“Kansas City’s got the best barbecue in the world, so when I came here Daddy Bruce (Randolph) was the only guy that did barbecue and I didn’t like it. So I said, ‘Hell, I’ll open my own place!’ ” said Dwight, who worked with preservationist Dana Crawford on the first Larimer Square location of what would become his Rib Cage restaurant.

A $2 million investment, four more Rib Cage locations, and other business ventures (including a successful real estate firm) followed. But by the mid-1970s Dwight’s heart had drifted back into the artistic realm.

“I started out as an artist,” Dwight said. “It was engineering and flying that was the intervention. I was born to make art.”

Dwight’s father was the one who wanted him to go into the sciences, despite the fact that Dwight had been creating art since the age of 2. By 14, Dwight was running a studio out of the back of his Kansas City house that his father had built for him, and Dwight was making enough money from selling pieces that he was able to buy his first car with the revenue. Growing up on a farm near Fairfax Municipal Airport, he also frequently visited the tarmac to sketch the World War II planes that used it as a stop-off.

“I drew every military plane they had there to scale and made catalogs of them,” said Dwight, who also began building detailed models of the aircraft, launching a creative give-and-take between science and art that continues for him today.

“If you Google ‘astronaut artists’ you’ll see that almost every Russian pilot, man or woman, who went into space is an artist. I think it’s the inspirational imagery of space. You just feel this need to interpret it, and not necessarily in a photographic way. Once you get above 60,000 or 70,000 feet, you see the curvature of the earth and the big, blue covering of the atmosphere. And in my training, I got these visions of space and the Milky Way that I would never get otherwise.”

In 1974, Dwight was commissioned to create a sculpture of Colorado’s first African-American Lt. Governor, George Brown, which quickly led to more commissions that have helped highlight the role of black pioneers in the American West. Since earning his Master of Fine Arts from the University of Denver in 1977, he has rarely looked back, crafting more than 18,000 sculptures for sale and public display.

“That sounds like a lot, but we cast things in editions and sell lots of them wherever we go,” he said.

For Robert Stone, director of “Chasing the Moon,” Dwight’s unusual life presented a new route into the story of America’s space program. Stone, an Oscar-nominated director and veteran of PBS’ “American Experiences” series (of which “Chasing the Moon” is part), didn’t want to simply present the same angles of technological trial and error (although that’s part of “Chasing the Moon,” too) but rather look at it from fresh perspectives, such as Dwight or Poppy Northcutt, the 25-year-old math-wiz who gained global attention as the first woman to serve in NASA’s all-male Mission Control.

“When we think of that breathtaking moment of the 1969 moon landing, we forget what a turbulent time that was,” said Mark Samels, executive producer of “American Experience,” in a press statement. “The country was dealing with huge problems — Vietnam, poverty, civil rights — and there was a lot of skepticism about the space program.”

Dwight was happy to tell his tale to Stone for his audio-only scenes in the series. He just had to be convinced of the legitimacy of the project, given the 50-plus years that have elapsed since his military career.

“He actually got in touch with me about three years ago and was pestering me all to hell, and I just kept dissing the guy,” Dwight said of Stone. “I was being honored at Kennedy Space Center in Orlando at the time, so he sent his team down there and I finally recorded about five hours of audio for him. That was just the beginning. But I was glad to help him because most of the (documentaries) tell this happy-happy tale where we get ready, go to space, come back and everything is just wonderful. This is a different way into that story, and a different story altogether.”