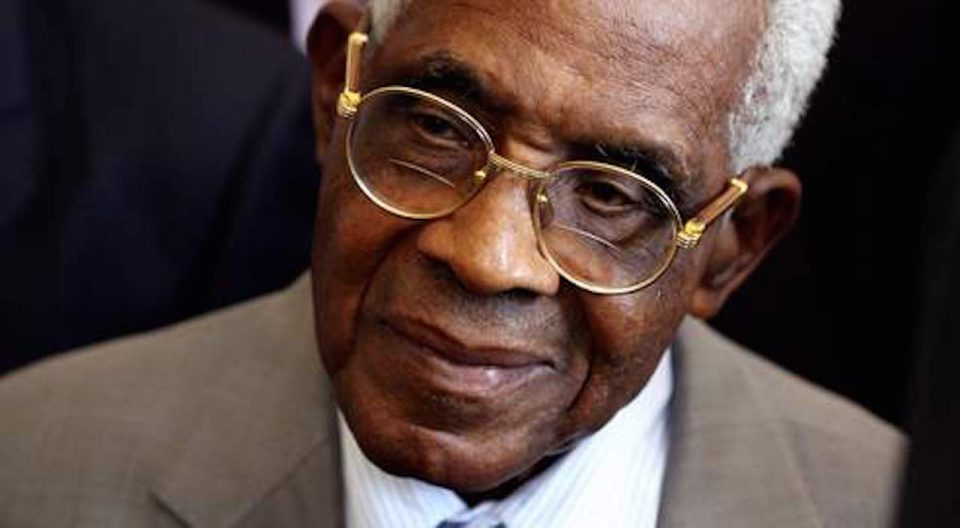

Aimé Césaire was born June 26, 1913, in Basse-Pointe, a small town on the northeast coast of Martinique in the French Caribbean. He attended the Lycée Schoelcher in Martinique, and the Parisian schools Ecole Normale Supérieure and the Lycée Louis-le-Grand.

His books of poetry include Lost Body (George Braziller, 1986), with illustrations by Pablo Picasso, Aimé Césaire: The Collected Poetry (University of California Press, 1983), and Return to My Native Land (Penguin Books, 1969). He is also a playwright and has written The Tempest (G. Borchardt, 1968), based on Shakespeare’s play, and A Season at Congo (Grove Press, 1966), among others.

About his work, Jean-Paul Sarte wrote: “A Césaire poem explodes and whirls about itself as a rocket, suns burst forth whirling and exploding like new suns—it perpetually surpasses itself.”

He is also the author of Discourse on Colonialism (Monthly Review Press, 1950), a book of essays which has become a classic text of French political literature and helped establish the literary and ideological movement Negritude, a term Césaire defined as “the simple recognition of the fact that one is black, the acceptance of this fact and of our destiny as blacks, of our history and culture.”

As a student, he and his friend, Léopold Senghor of Sénégal created L’Etudiant noir, a publication that brought together students of Africa and the West Indies. Later, with his wife, Suzanne Roussi, Césaire co-founded Tropiques, a journal dedicated to American black poetry. Both journals were a stronghold for the ideas of Negritude.

Césaire is a recipient of the International Nâzim Hikmet Poetry Award, the second winner in its history. He served as Mayor of Fort-de-France as a member of the Communist Party and later quit the party to establish his Martinique Independent Revolution Party. He was deeply involved in the struggle for French West Indian rights and served as the deputy to the French National Assembly. He retired from politics in 1993. Césaire died on April 17, 2008, in Martinique.