In 1796, a 22-year-old slave woman named Ona Judge fled President George Washington’s household for a life of freedom in New Hampshire.

When he was just 11 years old, George Washington inherited 10 slaves from his father’s estate. He would acquire many more in the years to come, whether through the death of other family members or by purchasing them directly. When he married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759, she brought more than 80 slaves along with her, bringing the total number of enslaved men, women, and children at Mount Vernon to more than 150 by the time the Revolutionary War began.

Ona Judge was born around 1773. Her mother, Betty, was a “dower slave,” part of the estate of Martha’s first husband; her father, Andrew Judge, was a white indentured servant who had recently arrived in America from Leeds, England. After fulfilling his four-year work contract at Mount Vernon, Andrew Judge moved off the plantation to start his own farm. As children born to enslaved women were considered the property of the slaveholder, according to Virginia law, his daughter remained in bondage.

Ona, more commonly known as Oney, moved into the mansion house when she was just 9 years old. Like her mother, she became a talented and highly valued seamstress and was later promoted to become Martha Washington’s personal maid. When Washington headed to New York City in 1789 for his inauguration as president, Oney was one of only a handful of slaves the couple took with them. Late the following year, when the federal capital moved to Philadelphia, the presidential household moved with it.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate.

With an active and growing free black community of some 6,000 people, Philadelphia had become the nation’s leading hotbed of abolitionism. In fact, as Erica Armstrong Dunbar writes in her new book, “Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge,” Oney would have been in the minority as a slave in Philadelphia; fewer than 100 slaves lived within city limits in 1796. To evade a gradual abolition law that took effect in Pennsylvania in 1780, the Washingtons made sure to transport their slaves in and out of the state every six months to avoid them establishing legal residency.

As the first lady’s body-servant, Judge helped dress her mistress for special events, traveled with her on social calls, and ran errands for her. Over more than five years in Philadelphia—traveling in and out every six months—she met and became acquainted with members of the city’s free black community and former slaves who had gained their freedom under the gradual abolition law. Such interactions undoubtedly fueled her thinking about slavery, the changing laws regarding the institution, and the possibilities of freedom.

In the spring of 1796, when she was 22 years old, Judge learned that Martha Washington planned to give her away as a wedding gift to her famously temperamental granddaughter, Elizabeth Parke Custis. As Dunbar writes, “Martha Washington’s decision to turn Judge over to Eliza was a reminder to Judge and everyone enslaved at the Executive Mansion that they had absolutely no control over their lives, no matter how loyally they served.”

So, as the household prepared for the Washingtons’ return to Mount Vernon for the summer, Judge made plans for her escape. On May 21, 1796, she slipped out of the mansion while the president and first lady were eating their supper. Members of the free black community helped her get aboard a ship commanded by Captain John Bowles, who sailed frequently between Philadelphia, New York, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. After a five-day journey, Judge disembarked in that coastal city, where she would begin her new life.

Martha Washington

Martha Washington

With a free black population of some 360 citizens and virtually no slaves, Portsmouth was different from any place Judge had ever known. She found lodging within the free black community, which was accustomed to aiding fugitive slaves, and supported herself doing domestic work, one of the few opportunities available for women of color.

During the summer after she escaped, Judge was walking in Portsmouth when she saw Elizabeth Langdon, the daughter of New Hampshire Senator John Langdon. Betsy Langdon recognized Oney, having encountered her before when calling on Martha Washington, a family friend, or her granddaughter Nelly Custis. After Judge passed by without acknowledging her, Betsy likely told her father of the sighting, and her father felt obligated to notify Washington of his fugitive slave’s whereabouts.

Trying to act discreetly, Washington got in contact with Joseph Whipple, the collector of customs in Portsmouth and the brother of famed Revolutionary General William Whipple. When Whipple tracked Judge down (by falsely advertising that he was seeking a female domestic for his home), he asked her about her reasons for fleeing bondage and offered to negotiate on her behalf. He subsequently wrote to Washington that she had agreed to return, on the condition that she be freed when Martha Washington died.

Dunbar writes in her book that Judge never intended to honor this agreement: “She told Whipple what he wanted to hear, agreed to return to her owners, and left his presence with no intention of ever keeping her word.” In any case, Washington bluntly refused Whipple’s proposal, writing that “To enter into such a compromise…is totally inadmissible.” Though he might be in favor of the gradual abolition of slavery, the president continued, he didn’t want to reward Judge’s “unfaithfulness” and inspire other slaves to try and escape.

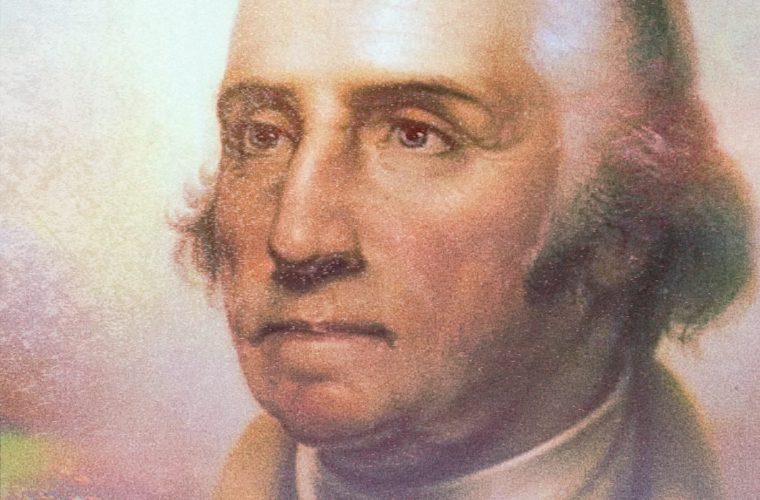

A depiction of George Washington during a harvest

A depiction of George Washington during a harvest

By the 1780s, Washington’s feelings about slavery had changed, and he expressed his uneasiness with the institution to close friends, including his Revolutionary War comrade the Marquis de Lafayette. But as his reaction to Judge’s escape made clear, Washington was not ready to give up on the bound labor on which his Virginia plantation—and his life—was built. Far from a passive bystander in the perpetuation of slavery, Washington at this point was actively engaged in returning Judge to his (or his wife’s) possession.

With antislavery sentiment growing in New Hampshire, and Washington’s influence waning as his term ended, Whipple did little more to pursue Judge on his behalf. Safe for the time being, she started building a life in Portsmouth and married Jack Staines, a free black sailor, in early 1797.

Though marriage gave her some additional legal protection, Ona remained vigilant–with good reason. In August 1799, Washington asked his nephew, Burwell Bassett Jr., to try and seize Judge and any children she may have had on his upcoming business trip to New Hampshire. When Bassett dined with Langdon and told him of his intention, the senator quickly got word to Ona through one of his servants. Jack Staines was at sea at the time, but Ona managed to escape to the neighboring town of Greenland, where she and her infant daughter hid with a free black family, the Jacks until Bassett left Portsmouth, empty-handed.

Four months later, George Washington died, freeing all of his slaves according to his will. Though the gesture was far from meaningless, it didn’t go far enough. Martha Washington, who lived until 1802, couldn’t even legally have emancipated her slaves upon her death (including, technically, Oney Judge Staines and her children), as they were part of her inheritance from her first husband and by law went to her surviving grandchildren. In the end, Washington and his fellow founders would push the hard decisions about slavery off onto future generations of Americans–with explosive consequences.

Ona Judge Staines lived with her husband and their three children until Jack’s death in 1803. After briefly holding a live-in position with the Bartlett family in Portsmouth, Ona left and moved with her children into the home of the Jacks family, where they remained. Work was scarce, and Ona’s son, William, is believed to have left home in the 1820s to become a sailor, like his father. Her two daughters, Eliza and Nancy, were sadly forced into indentured servitude; both died before their mother. After she became too old for physical labor, Ona herself lived in poverty, relying on donations from the community.

Despite all the hardships, Ona enjoyed the benefits of a life of freedom: She taught herself to read and write, embraced Christianity, and worshiped regularly at a church of her choice. Several years before her death in 1848, she granted two interviews to abolitionist newspapers recounting her journey from bondage. When a reporter from the Granite Freeman asked her if she regretted leaving the relative luxury of the Washingtons’ household, as she had worked so much harder after her escape, Ona Judge Staines memorably replied: “No, I am free, and have, I trust been made a child of God by the means.”