Have you ever wondered why many older African Americans like to leave early in the morning when they head out for a road trip? It’s likely something they learned to do as a matter of safety years ago when many of them used a “Green Book” to help navigate.

Many of you may have first learned about the “Green Book” from the movie it inspired.

Now the National Civil Rights Museum is paying tribute to the book that changed the culture of travel for those brave enough to venture out.

As the first African American woman to head a parish in the Episcopal Diocese of West Tennessee, Rev. Dorothy Wells knows the world is changing. But what was likely one of her most impressive lessons about change came from her parents and the story of their honeymoon in 1959.

“So there were things that I didn’t understand about the limitations of African Americans’ ability to travel and go and do things,” said Wells. “Because, obviously, accommodations were not open for people, and that was why there was such a thing as the ‘Green Book’.”

Wells’ parents, Willie Lee and Elbert Sanders used the “Negro Motorist Green Book” to plan in minute detail the entirety of their honeymoon through the segregated south — from Mobile, Alabama to Roanoke, Virginia.

It took them about six days — one way — to make the trip.

“Because if you wandered into a place where African Americans are not welcome, it could be worse than not safe,” said Wells. “You could end up actually being killed.”

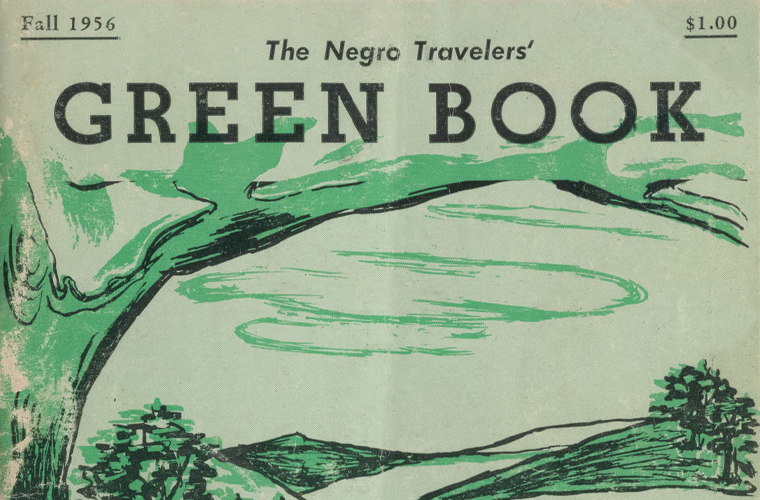

Created in the 1940s by a New York postman named Victor Hugo Green, the “Green Book” was a travel guide that listed safe and welcoming places for African Americans to eat, sleep or visit while traveling. Many of them were private homes.

“Some of them, as one of the houses that my parents stayed in on the trip, were just homes,” said Wells.

The “Green Book” also helped travelers determine which places to avoid after dark.

“And there were also places known as Sundown Towns,” said Dr. Noelle Trent with NCRM. “So there are places that you cannot drive in past sundown because they’re not welcoming to African Americans. So it’s literally a guide to navigating the country for African Americans.”

Trent, who is the director of Interpretation, Collections, and Education for NCRM, says the “Green Book” was regional at first but quickly expanded across the country and internationally by the time the Civil Rights Act was signed into law.

While dispensing life-saving information for African American travelers, since the “Green Book” was frequently updated it also gave black businesses a way to get the word out.

“We see businesses arising to accommodate the demand,” said Trent. “In 1964, the Lorraine Motel where the museum is housed did a major renovation and there was air conditioning, so they had major advertising to entice people to stay when they were driving through Memphis.”

Even with the “Green Book,” a lot of people still traveled in fear, particularly those who lived in areas where black businesses weren’t prevalent.

When I was a little girl, my father was stationed at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, and I remember us all piling into the car to take trips home to Georgia. Now that was in the early to mid-1960s. One thing I remember most about those trips is we never stopped — not for a hotel, a restaurant, or a restroom. My mom would fry up a big batch of chicken that we’d eat along the way, fill up a big thermos with soup and another big thermos with coffee, and off we’d go. Now, mind you, that was an 18- to 20-hour trip. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I realized why.

“One of the important things about the ‘Green Book’, I also think, is about the legacy of the ‘Green Book’ and how it impacts African Americans’ sense of travel,” said Trent. “That sort of legacy of how African Americans travel, how to navigate the area, that’s something that continues with us even now where we see African Americans documenting their interactions with police, right? It’s a legacy that comes out of understanding the need to survive with travel.”

When Wells traveled with her parents in the ’70s, including retracing their honeymoon route, it was much safer. But she was still able to get a better grasp of just what was at stake for her parents all those years ago.

“And I remember my father getting me out of the car and taking me by the hand and walking me in, and he’s asking for the room and he’s putting his money down on the counter and he’s standing up so proud,” said Wells.