John Woodruff was one of several African-American athletes who won gold medals at the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. Sometimes referred to as the Nazi Olympics, the 1936 games were blighted by the political ideology of the host country, which disdained the contributions of athletes who were not of white, northern European stock. Woodruff’s gold medal in the men’s eight hundred meter race, together with teammate Jesse Owens‘s four gold medals, proved the Nazis wrong. “I was very proud of that achievement and I was very happy—for myself as an individual, for my race, and for my country,” said Woodruff of his win, according to Highlights for Children writer Angie Kay Dilmore.

When Woodruff died in 2007, he had been the last surviving member of the U.S. track and field team for the memorable 1936 Olympics. He was born on July 5, 1915, in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town about fifty miles southeast of Pittsburgh, and was one of twelve children in his family. His grandparents had been slaves, and his father worked at a plant that produced coke, a byproduct of coal. During his teens, Woodruff played football for his high school team, but the long practices interfered with his chores, so his mother ordered him to give up the sport.

Woodruff was already known as a fast runner from the laps his football team did during practice sessions, and the track coach convinced him to join the other team, assuring him that the after-school practices were not as long as those for football. In 1935 Woodruff broke the national high school record for the one mile, running it with a time of 4:23.4. He gained further attention when he ran the 880-yard race in two separate events twice in the same week. This was known as the half-mile event, and Woodruff’s time was equally astonishing, with dual finishes of 1:55.1.

Enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh

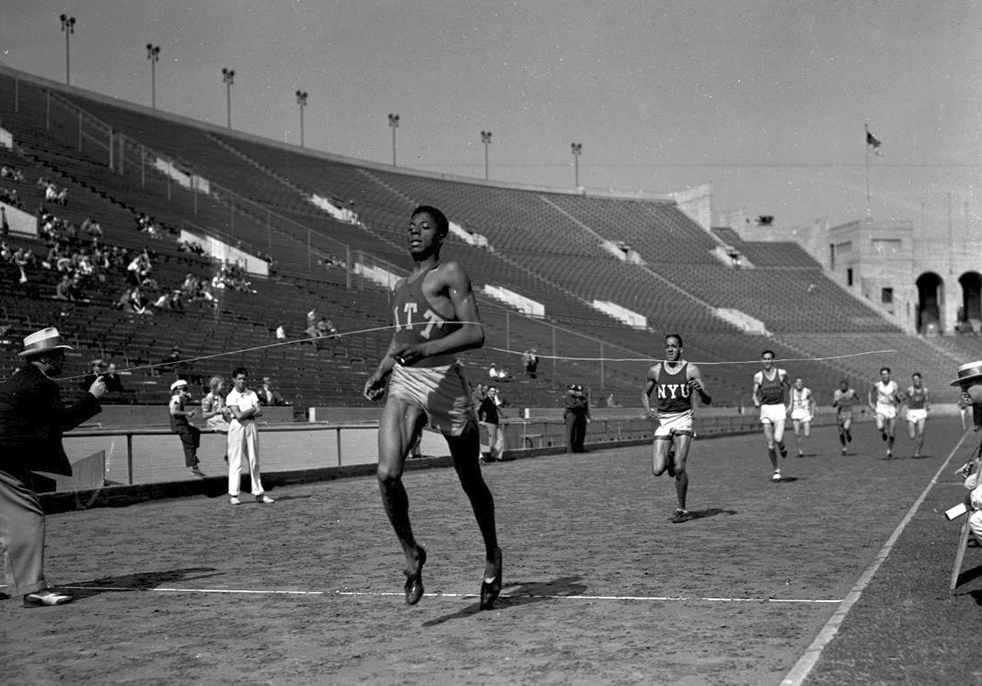

A few local business owners realized that Woodruff had college potential, so they arranged for him to go to the University of Pittsburgh on scholarship. He left home with twenty-five cents to his name, boarded at the black YMCA and work as a groundskeeper, and was sometimes short of food. Nevertheless, he emerged as a star athlete at Pitt, as the school was known, and in the spring and early summer of 1936, he began to earn notice in the national media for his athletic prowess. Standing six feet, four inches tall, he had a stride that was measured at almost ten feet and caused a sensation during the U.S. Olympic trials for track and field athletes. He even beat a heavily favored runner in the eight hundred meters with a time of 1:49.9—just a tenth of a second slower than the world record at the time.

Woodruff sailed for Germany in mid-July with other members of the U.S. Olympic team onboard a ship bound for Hamburg to reach Berlin in time for the August 1 opening day of the 1936 Summer Games. “I’d never been so far away from home,” he recalled to Dilmore. Berlin, the German capital, was also the showcase city for the Nazis, a right-wing fascist party that had seized power three years earlier. Believing in the superiority of the German race above all others, the Nazis began implementing harsh anti-Semitic laws and issuing spurious “studies” that claimed that peoples other than northern European whites were inferior in intelligence, physical strength, and even moral character.

Woodruff’s teammate Jesse Owens was the first African American to win a gold medal at the games, taking the first of his four on August 3 in the one-hundred-meter sprint. Woodruff’s specialty, the eight-hundred-meter race, was scheduled for the next day. He was not expected to place, however, for there were several more experienced runners—including previous Olympic-medal winners—and this would be his first international competition. The two best competitors were Mario Lanzi of Italy and Phil Edwards, a black Canadian runner who had just finished his medical-school studies. At the three-hundred-meter mark, Woodruff found himself boxed in by the other runners, so he made the kind of error that usually only amateur runners do: he slowed and then stopped altogether, which stunned the crowd. As he recalled in a 2006 New York Times interview with Frank Litsky, the Canadian had “set the pace, and it was very slow. On the first lap, I was on the inside, and I was trapped. I knew that the rules of running said if I tried to break out of a trap and fouled someone, I would be disqualified…. I’ve heard people say that I slowed down or almost stopped. I didn’t almost stop. I stopped, and everyone else ran around me.”

Woodruff was then able to move to an outside lane and pick up speed. He vaulted from last place to pass all the other runners, then briefly lost the lead to Edwards but won with a time of 1:52.9. Arthur J. Daley, a New York Times correspondent, filed a report in which he described it as “one of the strangest races ever run in the games,” and noted that Woodruff’s move to the outside likely added another fifty meters to the total distance he ran to win the event. Woodruff’s medal was one of twenty-four won by U.S. athletes at the Berlin Games, with eight of those by African-American Olympians.

Born John Youie Woodruff on July 5, 1915, in Connellsville, PA; died of atrial fibrillation and chronic renal failure, October 30, 2007, in Fountain Hills, AZ; son of a coke plant employee; the first marriage ended; married Rose, 1970; children: (from first marriage) Randy and John Jr. Military service: Commissioned lieutenant in the U.S. Army during World War II; served again during the Korean War and retired in 1957 with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Education: the University of Pittsburgh, bachelor’s degree; New York University, master’s degree in sociology, 1941.

Career: Worked as a teacher and track coach in suburban New York City and New Jersey, after 1957; also worked as a parole officer, welfare investigator, and director of a Police Athletic League.

Memberships: National Track and Field Hall of Fame; Penn Relays Wall of Fame, Franklin Field, University of Pennsylvania (charter member).

Awards: Olympic Gold Medal, 1936.

Robbed of World Record?

Woodruff was feted with a parade back in Connellsville, but he still lived at the YMCA and worked as a groundskeeper when he returned to Pitt. He won the eight hundred meter at the 1937 Amateur Athletic Union national championships, and on July 18, 1937, newspaper headlines heralded his new world record in the eight hundred meters with a time of 1:47.8 at the Pan-American Track and Field Games in Dallas, Texas. Three days later, however, Amateur Athletic Union officials announced the result of their postrace measurements of the temporary track set up for the event at the Cotton Bowl and found the track to have been improperly laid out. It was actually six feet short of eight hundred meters, they said, which automatically invalidated Woodruff’s time—and his world record. Nearly seventy years later, the Dallas Morning News columnist James Ragland wrote about the embarrassing turn of events, which took place at a time when Dallas and other southern cities were still deeply segregated. “How could the chief engineer measure it within 1/1,000 of an inch beforehand and then find it 6 feet short?” Woodruff wondered when Ragland interviewed him. “That was a big joke to me.”

Woodruff held the National Collegiate Athletic Association title in the 880-yard for three years running, from 1937 to 1939. His last race was at the 1940 Compton (California) Invitational, in which he won the eight hundred meter with a time of 1:48.6, a new U.S. track and field record that held until 1952. He had hoped to compete in the 1940 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, but that year’s games were canceled due to the outbreak of war in Europe. He enrolled instead at New York University, where he earned a master’s degree in sociology in 1941 and then enlisted in the U.S. Army. Commissioned as a lieutenant, he helped defeat the Nazis in World War II and reenlisted when the Korean War began in 1950. After commanding two battalions in that conflict, he remained in the service and retired in 1957 with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Woodruff spent the rest of his years as a teacher and track coach in suburban New York City and New Jersey. He also worked as a parole officer and welfare investigator, and occasionally officiated for track meets at Madison Square Garden. In March of 1965, he was one of several prominent athletes who ran legs for the Freedom Run from Harlem to Washington, an event staged as a protest against one of the last, bitter episodes of violence in Selma, Alabama, between state authorities and voting-rights advocates during the civil rights movement.

In his later years, Woodruff suffered from poor circulation and kidney problems, and both legs were amputated below the knee. According to Michael Carlson of the Guardian, Woodruff once said, “I’d rather be without my legs, and have a good mind.” He died on October 30, 2007, in Fountain Hills, Arizona, at the age of ninety-two. He was survived by Rose, his wife of thirty-seven years, and two children from his previous marriage. His oak sapling that was given to all gold medalists at the 1936 Berlin Games was planted on the football field in Connellsville. A plaque commemorating Woodruff’s achievement is located at the tree, which had grown to nearly eighty feet in height by the time of his death.