(From left) Viola Jackson, mother of Jimmie Lee Jackson, his cousin Rachel Thomas and grandfather Cager Lee arrive at the hospital in Selma, Ala., in 1965 to claim the body of the slain 26-year-old.

Fifty years ago this month, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference mounted demonstrations in Selma to stop the white obstruction of black voter registration there in Dallas County.

Protests spread 25 miles up the road from Selma to Marion (pop. 3,500), the government seat of Perry County, where Coretta Scott King had grown up.

First, they wanted to introduce democracy to the county. Although blacks were a clear majority, only a handful had been allowed to register to vote. And they wanted paved streets in black neighborhoods.

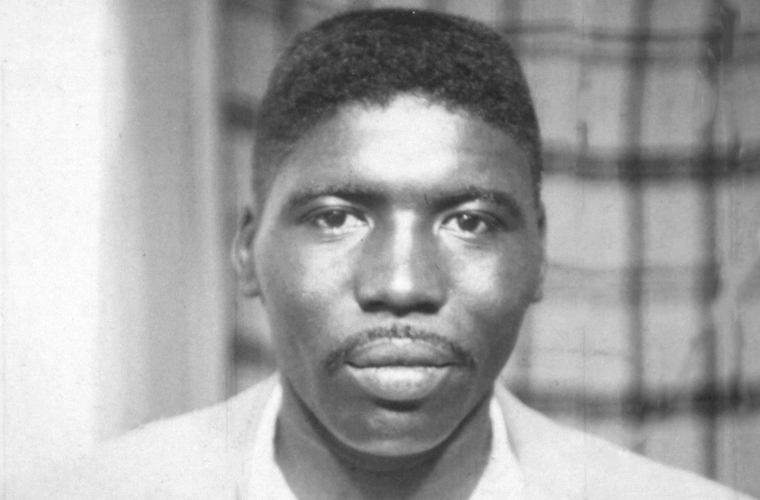

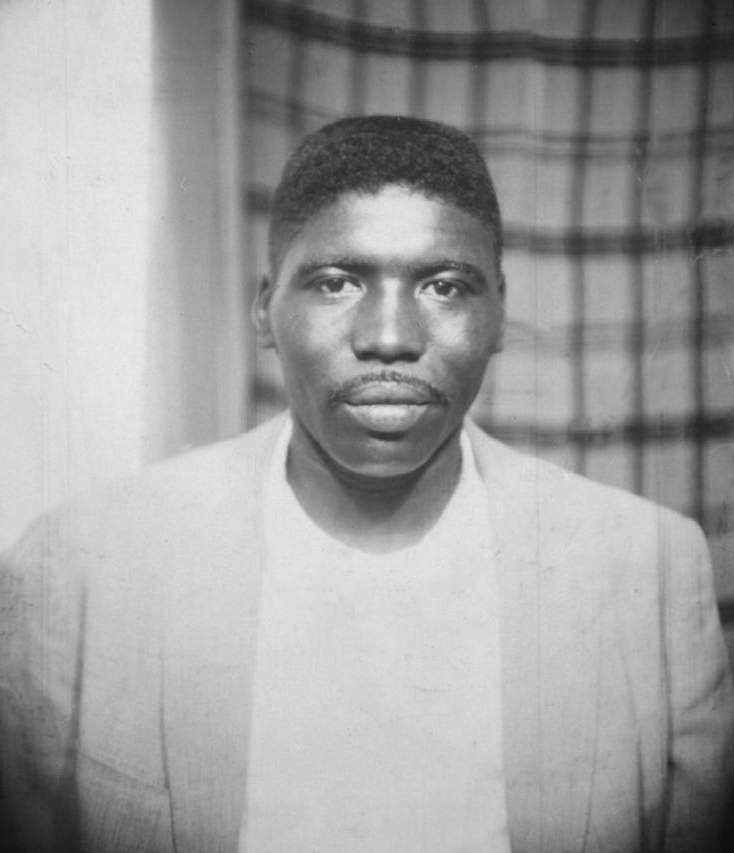

Jimmie Lee Jackson was fatally shot by a state trooper at a civil rights protest on Feb. 18, 1965.

Jimmie Lee Jackson was fatally shot by a state trooper at a civil rights protest on Feb. 18, 1965.

On Feb. 3, 1965, the conference staged an event with great lens appeal, leading hundreds of black children on a march around Marion’s colonnaded antebellum courthouse.

Police stopped the demonstration and arrested more than 600 children for unlawful assembly. James Orange, a mountain-sized leadership conference organizer known as a gentle giant, was collared and jailed for causing their delinquency.

As days passed with Orange locked up, his peers grew concerned about his well-being.

On Feb. 18, King sent C.T. Vivian, one of his lieutenants, to speak at Zion Chapel Methodist Church in Marion. At 9:30 that night, 400 people lined up two-by-two and set out from the church for a short march up Pickens St. to the county jail.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (second from right) and associates lead a procession following the casket of Jimmie Lee Jackson during a funeral service in Marion, Ala., on March 1, 1965.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (second from right) and associates lead a procession following the casket of Jimmie Lee Jackson during a funeral service in Marion, Ala., on March 1, 1965.

Col. Al Lingo, Alabama’s public safety boss, was waiting with a phalanx of 50 state troopers spoiling for a fight.

The group had gone just a half-block when someone cut the electricity to the streetlights.

Obscured by darkness, helmeted troopers waded into the column of marchers, poking with cattle prods and flailing with nightsticks. At the same time, white townie thugs targeted the press, clubbing NBC’s Richard Valeriani and two UPI photographers, Pete Fisher and Reggie Smith.

Marchers fled the assault. Some made it back to the church, and others sought refuge at Mack’s, a black café.

One of those huddled at Mack’s was Jimmie Lee Jackson, 26, a farm laborer and church deacon regarded as quiet and contemplative.

He had planned to get out of Alabama and join the black migration north after finishing high school in the late ’50s. But he stayed in Perry County to look after his mother, Viola after his father died suddenly.

Mother and son were sides by side that night 50 years ago. Amid the chaos, Jimmie Jackson’s grandfather, Cager Lee, staggered into the café, bleeding from a trooper’s blow to the head.

The Jacksons tried to lead their kin out of Mack’s and to a hospital, according to witnesses. They were blocked by troopers, who clubbed Viola Jackson. When Jimmie Jackson interceded, another trooper shot him in the abdomen.

The next morning, as Marion mopped up the blood, reporters found Alabama’s governor 150 miles away in Gadsden, where he was being feted at “Gov. George Wallace Week.”

He blamed the violence on “career agitators.”

“I don’t want to jump to conclusions of what happened in the still of the night in a small community,” Wallace said. “You have to remember there were 400 Negroes trying to conduct a march and there was a lot of confusion going on.”

He added, “I am conducting a full investigation.”

But even Montgomery’s avidly segregationist Alabama Journal recognized the Marion events as a cop riot, calling it “a nightmare of state police stupidity and brutality.”

Jackson died eight days after he was shot.

“Jimmie Lee Jackson’s death says to us that we must work passionately and unrelentingly to make the American dream a reality,” King said in his eulogy. “His death must prove that unmerited suffering does not go unredeemed.”

Though Marion did not get much national attention, it motivated momentous civil rights events that followed.

Local activist Albert Turner suggested that protesters “carry Jimmie’s body to George Wallace and dump it on the steps of the Capitol,” and that became the inspiration for the five-day march along Highway 80 from Selma to Montgomery 50 years ago next month.

In spite of Wallace’s promise of a thorough probe, justice for Jackson was a long time coming.

The state police corporal who shot him, James Bonard Fowler, escaped indictment by an all-white Perry County grand jury in the fall of 1965. In 1966, he shot and killed another black man during a scuffle in a local jail near Birmingham, and two years later he was fired from the patrol after severely beating a fellow officer.

In 2005, John Fleming of the Anniston (Ala.) Star found Fowler, 70 years old, living on a farm in southern Alabama. Fowler admitted the shooting but claimed self-defense.

“Jimmie Lee Jackson was not murdered,” he said. “He was trying to kill me… That’s why my conscience is clear.”

But the story prompted black legislators in Alabama to demand a new investigation, and Fowler was indicted for murder in 2007. He eventually pleaded guilty to manslaughter, served a six-month jail sentence, and was released in 2011.

While Fowler’s comeuppance was modest, historians who keep track of racially motivated slayings from the civil rights campaign regard his prosecution as a significant example of delayed score-settling.