If you were black in Jackson, Miss., during the ’50s, there was no need to look for violence; it found you. And Luvaghn Brown was no stranger to it. At home, his abusive father readily beat him with extension cords, sticks, razor straps, wires, whatever he could get his hands on. In the streets, kids threw punches, flashed blades — Brown included — trying to prove their toughness. “I was always ready to fight,” he says. “It was part of being a man.” He once even beat up a white man who happened into the black part of town. Robbed him, too, for good measure. “It was just anger,” he says. “It was just, How do you fight back?”

Segregation was an inviolable way of life in Jackson. In the movie house, blacks sat upstairs in the balcony, and Brown recalls not being allowed to try anything on in the clothing stores. “If the clothes didn’t fit, your mother would have to sew them,” he says. “There were constant reminders that you were less than — that there are whites, and there is you. That’s the only way I can put it.”

Brown, who was 11 when Emmett Till was lynched in Money, Miss., a two-hour drive north of Jackson, also knew that you didn’t stay out late in certain parts of town. “Your parents would remind you that you don’t disrespect white people — you don’t disrespect anybody — but you certainly don’t challenge white people,” he says. “You don’t get involved with the cops. You stay where you belong. Because you never knew what was going to happen. People would disappear, end up in the river. You had to be careful. You look at someone the wrong way, and you could be dead. That kind of violence could take place at any time. And that’s how I grew up.”

Brown attended the “colored” school, making the 5-mile round-trip trek each day on foot as there was no bus to take him across town. Brown says that if there was one benefit to his segregated upbringing it was his education, as his teachers were all highly educated black professionals who cared for their students. “This was the only place they could work,” he says. “So basically we had the best of the best.”

One teacher, Mr. Harris, who taught physics, made a profound impression on Brown. “He was just a brilliant man,” Brown says. “And he would talk about his own experiences being an educated black man living in Jackson, and how he was treated.”

Mr. Harris was angry and felt things needed to change. Brown understood this well; he was aware of the anger building in him. He knew there was no point to his education if he didn’t act. “My answer to everything at that time was violence: You gotta hurt somebody,” Brown says. “It was about, How do you get your gun and go do stuff? And you knew that you weren’t going to win that battle.”

“You never knew what was going to happen. People would disappear, end up in the river. You had to be careful.”

Eventually, Brown learned to channel his anger, and found a way to fight back, helping to chip away at segregation and all its indignities. In the summer of 1961, he met Freedom Riders James Bevel and Bernard Lafayette. The two tried to recruit Brown, recognizing that with his toughness, intelligence, and speaking ability, he might be able to motivate others to help them with their plan to fill the Jackson jailhouse. Having lived in Jackson his whole life, Brown thought they were crazy. He knew only violence. “Nonviolence?” he recalls thinking. “You’ll get killed.”

He realized they were risking their lives, and this made an impression on him. “They really believed in what they were saying,” Brown says. “Part of what had gotten to me was that they had come to Jackson. It never occurred to me that anyone (would come here) to do anything.” So, just weeks after graduating from high school, Brown took his first step across the line drawn by Jim Crow: In July 1961, he and his friend, Jimmie Travis, walked into a Woolworth’s in downtown Jackson and asked to be served. He was 16 years old.

“We decided right then and there that it’s time for us to do something,” Brown says. “Just like that. We decided this was the day. Let’s go.”

The waitress refused to serve them and summoned the manager, who told them to leave. They refused. “The next folks we dealt with were the cops,” who also told them to leave, Brown recalls. They refused. And with that, the two teens were arrested.

When they got to jail fear took hold. That’s when it hit them: Nobody knows they’re there. “And I know that anything could happen,” Brown says. “The jailors could come in, beat us up. But that didn’t happen.”

The story made the local newspaper and the two were bailed out (to this day he doesn’t know who put up the money), but they caught hell for what they’d done from Bevel and Lafayette, and just about everyone else. This is not how this is done, they were told. They could’ve been killed. “They couldn’t go but so far because we were the only ones who had done anything,” Brown says.

Brown never returned home to his abusive father; instead, he made the civil-rights movement his adoptive family. He joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, registering blacks to vote in Mississippi. His efforts landed him in and out of jail — he was once sent to a penal farm for 42 days. Several times, he was beaten for not working, though it was nothing compared to the pain his father had inflicted on him. “I felt like telling the guard he was an amateur,” Brown says with a big laugh. Another time, a guard barked his name and he instinctively snapped back, “What?”

In an instant, a .45 was in his face. “He basically said, ‘I will kill you’ and I believed him,” Brown recalls. “I had no reason to.”

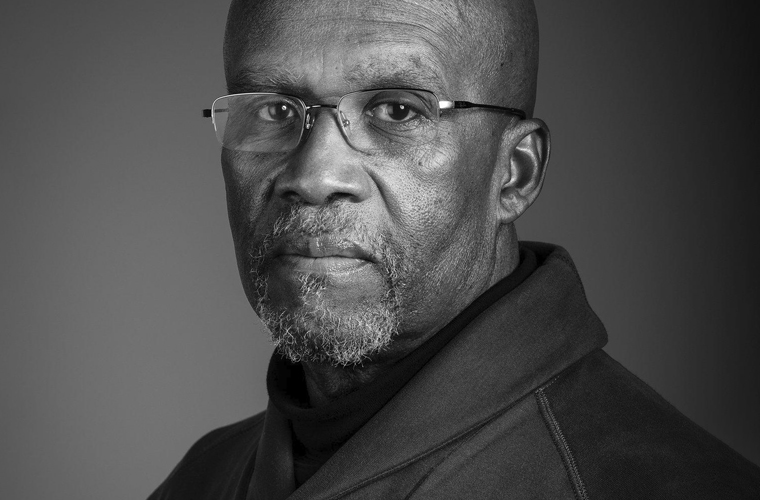

Today, Brown, 71, who is retired from PricewaterhouseCoopers, lives in a spacious home in Westchester County, north of NYC. He visits schools to share stories of his experiences in the movement, an endeavor that started when his daughter approached him about speaking at hers. There, he’ll reflect on the nights he spent in jail, the people he helped register to vote and the times he could’ve been killed. “I think a lot of what we did with the voting rights and civil rights, in general, was just incredible,” he says.

“They bring out the same film every year showing Dr. Martin Luther King,” Brown says of his school visits. “So I talk about the foot soldiers. I talk about people like (Southern Christian Leadership Conference co-founder) Bayard Rustin. I talk about him because he was important. There wouldn’t have been a March on Washington without Rustin. He organized it. He made things happen, and yet, you never hear his name.

“And people I worked with in Jackson,” he continues. “People who put their lives on the line, people who came on the Freedom Rides and stayed, like Joan Trumpauer. Joan stayed in Jackson. Somebody like that, I’ll talk about. Most people haven’t heard of her. That’s why I talk, so kids understand you don’t have to be Martin Luther King to do something to affect history.”