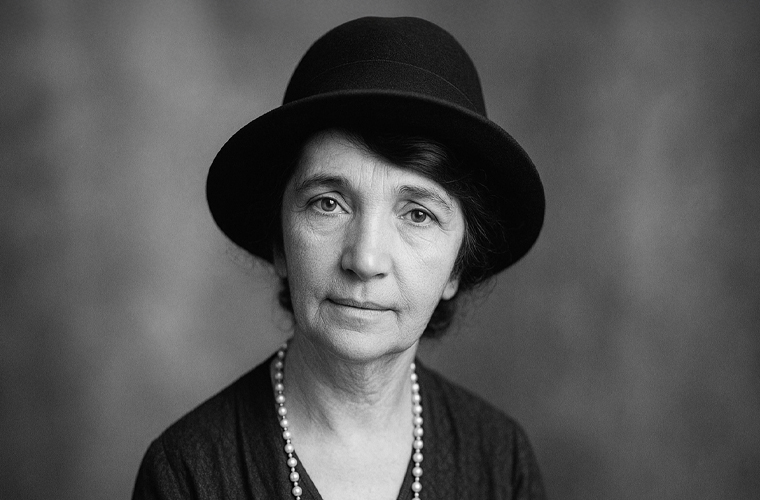

Margaret Sanger (1879–1966) is a polarizing figure in American history, celebrated by some as a pioneer of reproductive rights and vilified by others for her association with eugenics and racially charged rhetoric. As the founder of the American Birth Control League (later Planned Parenthood), Sanger championed access to contraception, but her legacy is deeply entangled with the eugenics movement, which has led to accusations of racism and elitism. This article explores Sanger’s life, her contributions to birth control, and the contentious aspects of her eugenics advocacy, providing a balanced look at her complex legacy.

Born Margaret Higgins in Corning, New York, Sanger grew up in a large Irish Catholic family, witnessing the toll of frequent pregnancies on her mother, who died young. This experience shaped her resolve to advocate for women’s reproductive autonomy. As a nurse in New York City’s Lower East Side, Sanger saw firsthand the desperation of women burdened by unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions. In 1916, she opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, defying laws that deemed contraception obscene. Her activism led to arrests but also sparked a national conversation about women’s right to control their bodies.

Sanger’s 1920 book, Woman and the New Race, argued that birth control could liberate women and reduce poverty by allowing families to plan smaller, healthier households. She founded the American Birth Control League in 1921, which became Planned Parenthood in 1942. Her work laid the groundwork for the 1965 Supreme Court decision Griswold v. Connecticut, which legalized contraception for married couples.

The early 20th century was a time when eugenics—the pseudoscientific movement to improve the human population through selective breeding—was mainstream in Western intellectual circles. Sanger embraced aspects of eugenics, believing birth control could reduce the birth rates of those she deemed “unfit,” a term often applied to the poor, disabled, or non-white populations. Her 1921 article, “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda,” stated, “The most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the over-fertility of the mentally and physically defective.” Such language aligned with eugenicists who supported policies like forced sterilizations and immigration restrictions.

Sanger’s views were shaped by the era’s prevailing ideas. She collaborated with eugenics organizations, such as the American Eugenics Society, and spoke at events alongside figures who promoted racial hierarchies. Her 1939 “Negro Project,” aimed at providing birth control to Black communities in the South, has drawn particular scrutiny. While Sanger argued it was about improving health outcomes, critics point to her correspondence, such as a letter to Clarence Gamble, where she suggested recruiting Black ministers to avoid the perception that “we want to exterminate the Negro population.” Though she clarified she intended to build trust, the phrasing and her alignment with eugenicists fuel ongoing debates about her motives.

Critics argue Sanger’s eugenics advocacy was inherently racist, as it targeted marginalized groups for population control. Her writings often reflected stereotypes, such as describing immigrants and the poor as burdens on society. In The Pivot of Civilization (1922), she wrote of the need to curb the reproduction of those “whose progeny is already tainted.” Such statements, combined with her support for policies like the 1927 Buck v. Bell decision (upholding forced sterilizations), paint a troubling picture.

Defenders, however, argue Sanger was a pragmatist navigating a deeply flawed era. They note she worked with Black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois and supported clinics in Harlem to serve Black women, suggesting her focus was on universal access to contraception, not racial extermination. They also point out that eugenics was endorsed by many progressives, including Theodore Roosevelt and W.E.B. Du Bois himself, reflecting the era’s scientific consensus. Sanger’s primary goal, they argue, was empowering women, not enforcing racial hierarchies.

She even presented at a Ku Klux Klan rally in 1926 in Silver Lake, N.J. She recounted this event in her autobiography: “I accepted an invitation to talk to the women’s branch of the Ku Klux Klan … I saw through the door dim figures parading with banners and illuminated crosses … I was escorted to the platform, was introduced, and began to speak … In the end, through simple illustrations, I believed I had accomplished my purpose. A dozen invitations to speak to similar groups were proffered” (Margaret Sanger, “An Autobiography,” Page 366). That she generated enthusiasm among some of America’s leading racists says something about the content and tone of her remarks.

In a letter to Clarence Gable in 1939, Sanger wrote: “We do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population, and the minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to any of their more rebellious members” (Margaret Sanger commenting on the ‘Negro Project’ in a letter to Gamble, Dec. 10, 1939).

Her own words and television appearances leave no room for parsing. For example, she wrote many articles about eugenics in the journal she founded in 1917, the Birth Control Review. Her articles included “Some Moral Aspects of Eugenics” (June 1920), “The Eugenic Conscience” (February 1921), “The Purpose of Eugenics” (December 1924), “Birth Control and Positive Eugenics” (July 1925) and “Birth Control: The True Eugenics” (August 1928), to name a few.

Sanger’s contributions to reproductive rights are undeniable. Planned Parenthood, which she helped establish, remains a cornerstone of women’s healthcare, providing services to millions. Yet her eugenics ties have led to calls to reevaluate her legacy. In 2021, Planned Parenthood’s New York chapter removed Sanger’s name from a clinic, acknowledging her “harmful connections to the eugenics movement.” Scholars continue to debate whether her views were malicious or merely reflective of her time’s biases.

The controversy surrounding Sanger raises broader questions about historical figures and moral complexity. Her work empowered women but operated within a framework that devalued certain lives. Understanding her legacy requires grappling with both her achievements and the troubling ideologies she endorsed.

Margaret Sanger’s life embodies the contradictions of a reformer working within a flawed system. Her advocacy for birth control transformed society, but her entanglement with eugenics and racially charged rhetoric casts a shadow. Whether viewed as a racist eugenicist or a flawed visionary, Sanger’s story underscores the need to critically examine heroes and their contexts. Her legacy remains a battleground for debates about reproductive justice, race, and the ethics of social reform.

Selected Quotes by Margaret Sanger

On Sterilization and Eugenics (1919):

“While I personally believe in the sterilization of the feeble-minded, the insane, and syphilitic, I have not been able to discover that these measures are more than superficial deterrents when applied to the constantly growing stream of the unfit. They are excellent means of meeting a certain phase of the situation, but I believe in regard to these, as in regard to other eugenic means, that they do not go to the bottom of the matter.”

Source: “Birth Control and Racial Betterment,” The Birth Control Review, February 1919.

Eugenics and Birth Control (1919):

“Eugenics without birth control seems to us a house built upon the sands. It is at the mercy of the rising stream of the unfit.”

Source: “Birth Control and Racial Betterment,” The Birth Control Review, February 1919.

On Human Waste (1920):

“Stop our national habit of human waste.”

Source: “Woman and the New Race,” Chapter 6, 1920.

On Childbearing and Health (1920):

“By all means, there should be no children when either mother or father suffers from such diseases as tuberculosis, gonorrhea, syphilis, cancer, epilepsy, insanity, drunkenness, and mental disorders. In the case of the mother, heart disease, kidney trouble, and pelvic deformities are also serious barriers to childbearing. No more children should be born when the parents, though healthy themselves, find that their children are physically or mentally defective.”

Source: “Woman and the New Race,” Chapter 7, 1920.

On Population Control Measures (1932):

“The main objects of the Population Congress would be to apply a stern and rigid policy of sterilization and segregation to that grade of population whose progeny is tainted, or whose inheritance is such that objectionable traits may be transmitted to offspring; to give certain dysgenic groups in our population their choice of segregation or sterilization.”

Source: “A Plan for Peace,” 1932.

On Children and Inherited Conditions (1957):

“I think the greatest sin in the world is bringing children into the world who have a disease from their parents, who have no chance in the world to be a human being practically. Delinquents, prisoners, all sorts of things are marked when they’re born. That to me is the greatest sin that people can commit.”

Source: Interview with Mike Wallace, 1957.