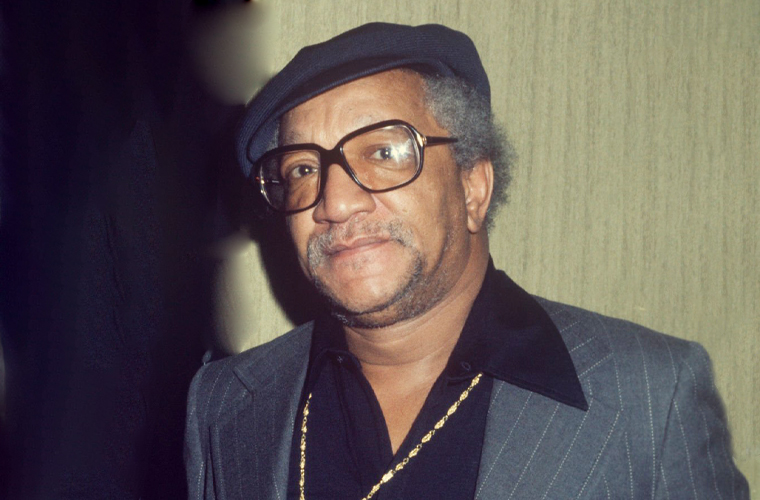

Redd Foxx, born John Elroy Sanford, was an iconic American comedian and actor who left an indelible mark on the world of comedy. With his unique style, quick wit, and boundary-pushing humor, Foxx became a trailblazer in the entertainment industry. This article aims to delve into the life, career, and lasting impact of this legendary comedian. Foxx was born on December 9, 1922, in St. Louis, Missouri. Growing up in a predominantly African-American neighborhood, he faced numerous challenges and hardships. However, it was during these formative years that Foxx discovered his passion for comedy. He would often entertain friends and family with his sharp sense of humor and natural comedic timing.

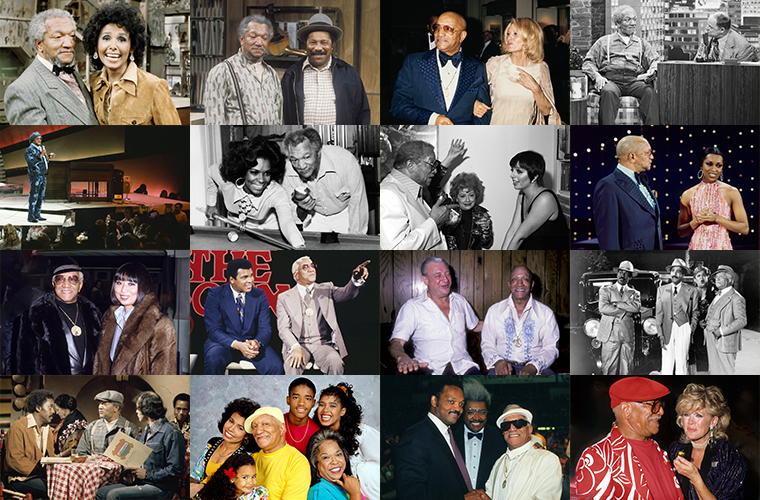

Foxx’s career in show business began in the 1940s when he started performing in clubs and theaters under the stage name “Redd Foxx.” He honed his craft through countless performances, gradually gaining recognition for his edgy and irreverent brand of humor. Foxx’s ability to tackle taboo subjects with a clever twist set him apart from other comedians of his time. Foxx’s career reached new heights in 1972 when he landed the role of Fred G. Sanford in the groundbreaking sitcom “Sanford and Son.” The show, created by Norman Lear, centered around the hilarious interactions between Foxx’s character and his son Lamont, played by Demond Wilson. Foxx’s portrayal of the cantankerous junk dealer resonated with audiences, and “Sanford and Son” became an instant hit.

The success of “Sanford and Son” catapulted Foxx into stardom and solidified his status as a comedy legend. His impeccable comedic timing, distinctive laugh, and memorable catchphrases, such as “You big dummy!” and “Elizabeth, I’m coming!” became ingrained in pop culture. Foxx’s ability to infuse his character with both humor and heart made him relatable to audiences of all backgrounds. While “Sanford and Son” was undoubtedly Foxx’s most significant success, his career extended far beyond the iconic sitcom. He released numerous comedy albums that showcased his raw talent and razor-sharp wit. Albums like “Laff of the Party” and “You Gotta Wash Your Ass!” further solidified Foxx’s reputation as a comedic genius.

Foxx also made notable appearances in films, including “Harlem Nights” alongside Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor. His ability to seamlessly transition between television and film demonstrated his versatility as a performer. Foxx’s contributions to the entertainment industry were recognized with several awards and accolades throughout his career.

Redd Foxx’s impact on comedy cannot be overstated. He paved the way for future generations of comedians by fearlessly pushing boundaries and challenging societal norms. His ability to tackle taboo subjects with humor and wit opened doors for others to follow. Furthermore, Foxx’s influence extended beyond the world of comedy. He was a trailblazer for African-American performers, breaking down barriers and providing representation at a time when it was sorely lacking. His success served as an inspiration to countless individuals who aspired to pursue careers in entertainment.

Tragically, Foxx passed away on October 11, 1991, at the age of 68. However, his legacy lives on through his timeless comedic performances and the laughter he brought to millions of people worldwide.

In conclusion, Redd Foxx was a comedic pioneer whose impact on the entertainment industry cannot be overstated. His unique style, boundary-pushing humor, and trailblazing spirit continue to inspire comedians to this day. Foxx’s ability to make people laugh while tackling important social issues is a testament to his talent and enduring legacy. He will forever be remembered as one of the greatest comedians of all time.