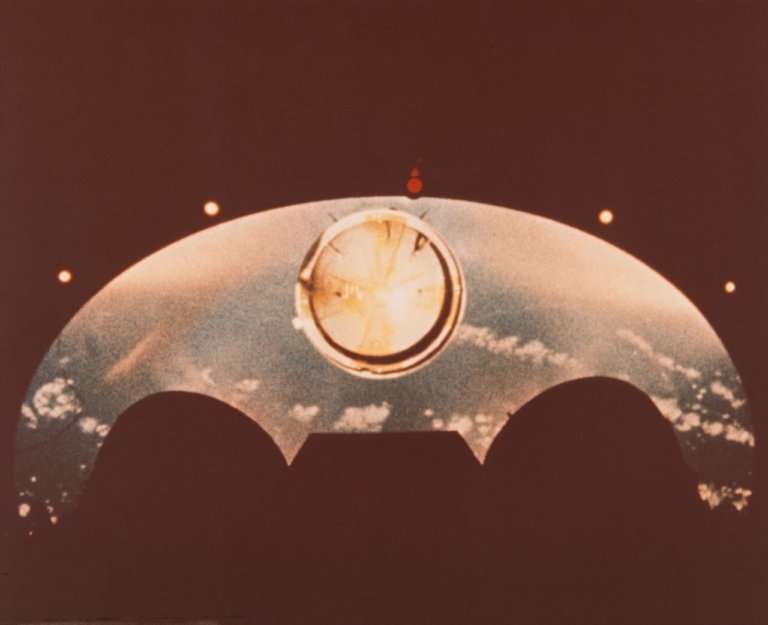

Shelby Jacobs designed a camera system that flew on the unmanned Apollo 6 flight in April 1968.

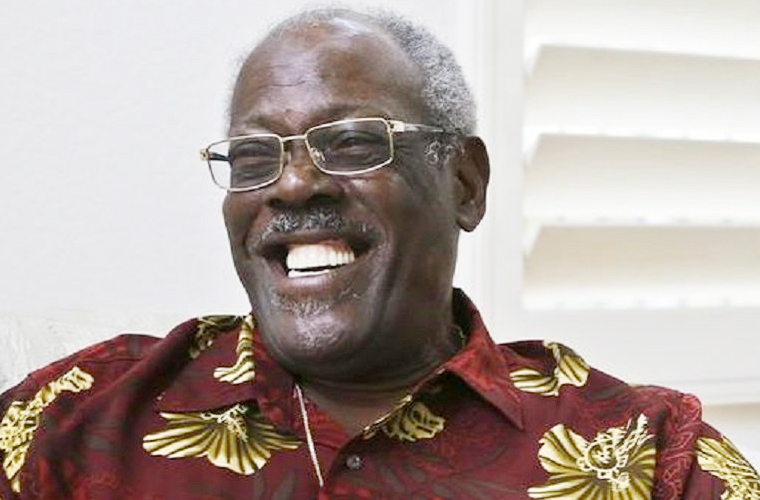

Growing up as the son of a preacher in the tiny black community of Val Verde, north of Santa Clarita, Shelby Jacobs encountered a lot of social barriers like so many black people during that period. Despite the above challenges, he stood out in many ways during his days in high school – as an athlete and senior class president. He subsequently earned a scholarship to the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) to study mechanical engineering after taking an aptitude test that showed a high proficiency in math and science.

This did not deter a determined Jacobs, who succeeded against all odds and went on to help the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) make space history under the Apollo Space program. The program involved a series of space flights undertaken by the United States with the goal of landing a man on the moon. Jacobs’ historic feat was achieved on April 4, 1968, when NASA’s Apollo 6 launch (the final unmanned Apollo test mission) took place under the United States Apollo program. Three years prior to this, Jacobs had been given the task of designing a camera system that could capture the rocket separations for the unmanned Apollo 6 launch. Within three years, he designed, installed, and tested the camera system, which eventually recorded the famous footage just seconds after the launch of the unmanned Apollo 6 flight in April 1968.

Apollo 6 launch, Saturn V Rocket, interstage section falls away.

Apollo 6 launch, Saturn V Rocket, interstage section falls away.

The film of the separation between the first and second stages of the vehicle is one of the most repeated images in space history, In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Jacobs said the video “proved the viability of the Saturn V rocket separation process. It was also the first time the video had captured the curvature of Earth from space.” His success was, however, eclipsed by the assassination of iconic civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr., that occurred on the same day of the Apollo 6 launch. That did not discourage Jacobs, as, in the next 15 years, he climbed the professional ladder of the space shuttle program, and reached the executive level of vice president.

Jacobs’ specialty was designing engine components, hydraulics, pneumatics, and propulsion systems. After his education at UCLA, he was hired at Rocketdyne, in Canoga Park, Calif., where he made detail and assembly drawings for the Mercury and Atlas projects. It is documented that at the time, just eight of Rocketdyne’s 5,000 engineers were black, and though Jacobs faced a lot of discrimination from his white colleagues, he chose to hang out with them, endured their racial comments, and challenged them when he could.

Jacobs, in the 1960s, transferred to Rockwell in Downey, where he spent the rest of his career before retiring in 1996. It was only about 10 years ago that he started receiving attention for his work after he was named a NASA “unsung hero.” After seeing the 2016 film, Jacobs and his wife, Elizabeth Portilla, started visiting space museums and encouraging them to highlight the hidden figures in the aerospace industry while advocating for minorities.

Shelby Jacobs.

Shelby Jacobs.

Now 83, Jacobs is finally getting his due as the Columbia Memorial Space Center in Downey, Calif., has announced that it will run an exhibit called “Achieving the Impossible: The Life and Dreams of Shelby Jacobs” through the spring. “The exhibit documents Jacobs’ achievements, a photo from his famous video, one of Jacobs’ old suits, his briefcase, his ID badges, family photos, and even one of the hand-carved pipes he often carried around with him at work,” reports the Los Angeles Times.

There will also be a daylong program at the museum on February 16 to celebrate Black History Month. NASA will later celebrate the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 (the first lunar landing by humans) this year and Jacobs would feature in several video and newspaper interviews while a biography is expected to be written about him. Despite the frequent segregation he faced during his long 40-year career in aerospace, Jacobs once said of his decision to pursue engineering instead of a trade: “I thought it better to prepare and not be able to achieve career goals than not prepare and live to regret it.”