A Black man who doubled as a detective for the police force managed to infiltrate the security detail of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) founder Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party, two entities for the African cause, and worked against its gains.

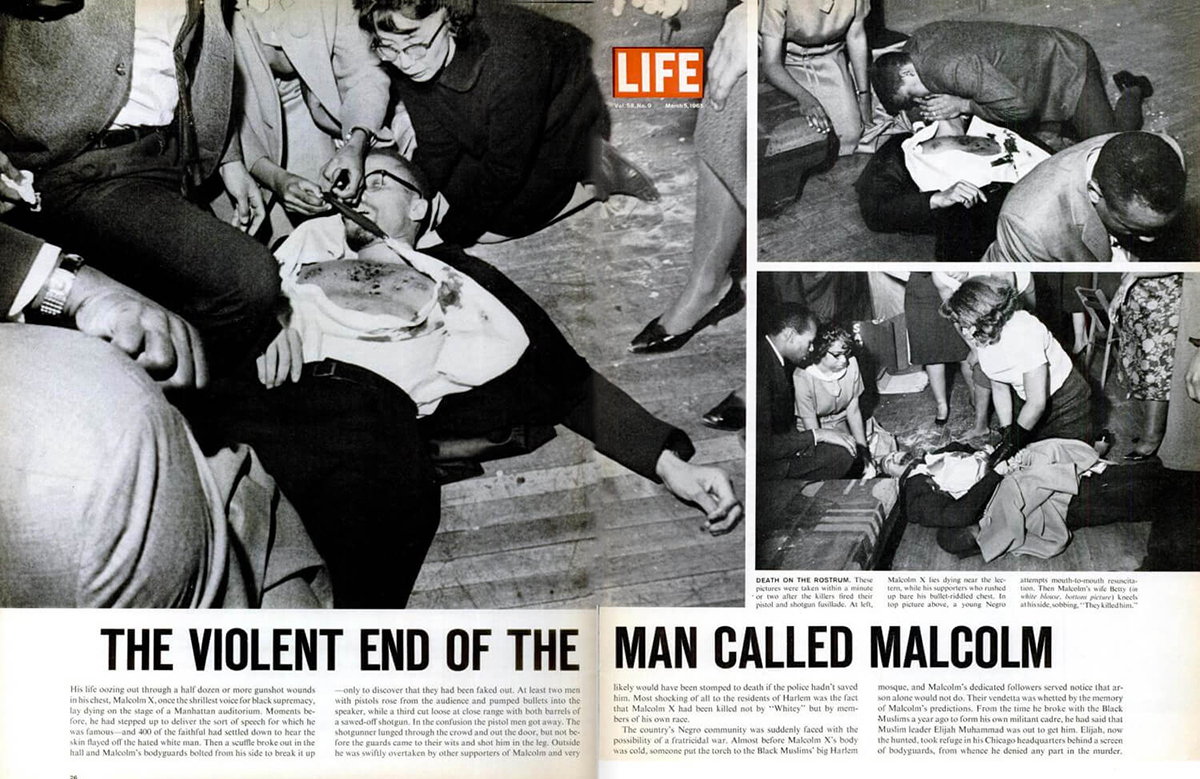

Eugene Roberts also called Gene Roberts was close by when Malcolm X was killed at the Audubon Ballroom on 21 February 1965.

In fact, Roberts was photographed trying in vain to resuscitate Malcolm X at the assassination. He was a man known affectionately within the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), an organization Malcolm X founded to bridge the gap between Africans on the continent and those in the diaspora as “Brother Gene” only to later be confirmed as an undercover agent with the Bureau of Special Services and Investigation (BOSSI) in the New York City Police Department (NYPD).

BOSS was a super-secret political intelligence unit nicknamed the Red Squad and when Roberts infiltrated the OAAU, he managed to become one of Malcolm’s chiefs of security while being an NYPD undercover cop. Two of the three men convicted of killing Malcolm X, Norman Butler and Robert 15X Johnson, were almost certainly not at the scene of the crime. The evidence points to a confluence of three groups involved in Malcolm X’s assassination: institutional forces (NYPD, FBI, CIA, etc.),

The Nation of Islam, and elements within Malcolm’s own circle after his split with NOI. What is clear is that all these groups had a vested interest in eliminating Malcolm X who had at the time of his death become a potent threat to the established system thanks to his mobilization of disgruntled Blacks as well as the working class. His growing partnership with Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah helped birth the OAAU molded on the continental Organization of African Unity of independent African states.

After the formation of (OAAU) and Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI), Malcolm prepared to release a new political program which would have likely included voter registration drives, local organizing against police brutality, and a call for the United Nations to denounce American racial practices as human rights violations. He was gunned down on the very day he was set to unveil it. To know for sure what roles infiltrators such as Ray Wood and Roberts played in Malcolm’s assassination, the NYPD has to release surveillance files and reports of undercover officers in the years surrounding the assassination, but the department has repeatedly refused to release them.

In the 1970s, the public learned about COINTELPRO and other secret FBI programs directed towards infiltrating and disrupting civil rights organizations during the 1950s and 1960s. J Edgar Hoover, who led the government’s COINTELPRO said… “There must be a goal of preventing a coalition of militant black nationalist groups, prevent the rise of a black messiah that can unify and electrify the black nationalist movement, along with preventing militant black nationalist groups and leaders from gaining respectability, by discrediting them to the community”.

Roberts is said to have grown close to Malcolm and though he was reporting on him, he had come to be fond of him and his death haunted his wife for decades who was also in the Audubon Ballroom. He is said to have been distracted by the assailants who killed Malcolm and when he shot one was also shot at except the bullet missed him by inches. But after Malcolm fell, Roberts was promoted to detective, by the NYPD and with that, he infiltrated the Black Panther Party.

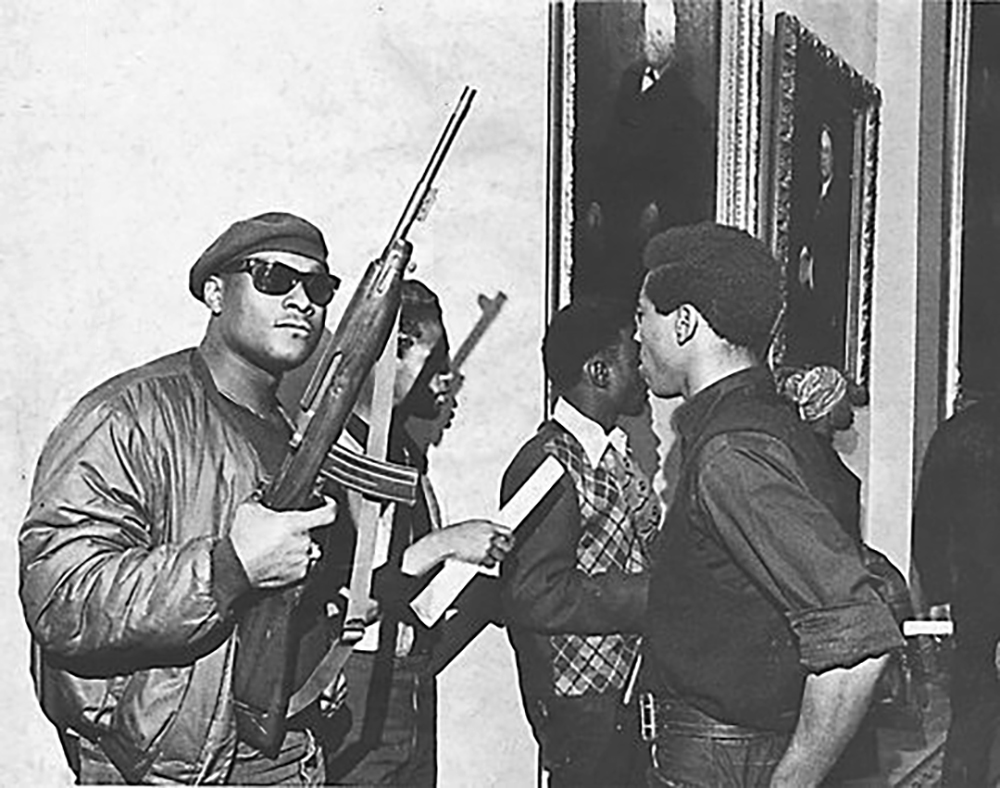

Roberts became a founding member of the New York chapter of the Black Panther Party, in July 1968, but had little to report on to handlers at BOSS.

“Nothing significant; usual black power rhetoric,” he is said to have noted on one occasion.

So when another undercover cop claimed to have managed to steal some dynamite that Lumumba Shakur, partner of Afeni Shakur had stashed, switching the real sticks for duds before bombs were planted at police stations, adding that a Panther sniper team was assigned to pick off cops as they fled from one precinct after the planned explosion and that a gunfight ensued between a highway police team and the panther snipers where they escaped, it must have surprised Roberts.

In the ensuing hearing, the prosecutors’ case was compromised with inconsistencies. Roberts had never testified in open court before, he was kept on the stand for six weeks and when he testified about the New York Panthers as being rebels without a clue and couldn’t have pulled off the crime they were being accused of, he was viewed as unhelpful to the prosecution as a witness. For the defense, he was mortifying. While being cross-examined by six white radical lawyers, they denounced him as “the trusted slave who would whip the other slaves when required,” and “secret agents . . . forced to sell their souls and forfeit their manhood.”

In the end, 21 of the panthers were charged with conspiring to blow up several police precincts, part of a railroad, the Bronx Botanical Garden, and five Manhattan department stores. However, Roberts who had taken the lead in the department-store operation and was aware no one he knew had done anything more than window shop must have been surprised as the Panthers. The “Panther 21” trial was the longest and most expensive criminal prosecution in the history of New York lasting some two years with the jury voting not guilty on all counts after two hours of deliberation.

Roberts during the Panther trials also shared how his undercover role was nearly discovered when a Panther came close to touching electronic equipment under his shirt while taping a heart‐shaped target to the garment. After the frightening experience of near discovery in the gun class, he said he no longer wore electronic transmission equipment to Panther meetings.

Several former cops said that Roberts struggled during his remaining years on the job. After the trial, Roberts was assigned to ordinary detective duties in the Bronx. He developed a drinking problem, which eventually cost him his marriage. He was given medals but never promoted.

Roberts gave an interview for a 1994 documentary called Brother Minister: The Assassination of Malcolm X. He noted: “There are a lot of people in the black community that consider me a traitor to my race and the community. . . . I felt then and I feel now . . . I would get some negative feedback. And I would get some positive feedback. I felt that it was a job. A job I felt was the right thing to do.”

He died alone in Virginia in 2008.