A couple of months ago, the eminent classicist Mary Beard was at the heart of a thunderous Twitterstorm. The BBC had made a cartoon film about Roman Britain for schoolchildren, featuring a family which their publicity blurb described, at one point, as typical; and the head of the family, a senior officer in the Roman army, was black.

When tweeters and bloggers accused the BBC of political correctness, Prof Beard leaped to its defense, saying that this could have been an officer from Algeria. And then all hell broke loose.

For those of us who are neither experts on Roman Britain nor professional headbangers, two simple conclusions seem to have emerged from an otherwise unedifying row. The first is that it’s certainly possible (though not at all typical) that some Romans who came here might have been dark-skinned enough to count as black. And the second is that a kind of politically correct manipulation of history is taking place in our culture. Getting present-day people to “relate” to the past is now a high priority; so the past, it seems, must be adapted to suit the present.

I don’t know whether that BBC series has reached the Tudors yet, but if and when it does, I hope the film-makers will read Miranda Kaufmann’s Black Tudors very carefully. For while she shows that the number of black people in Tudor England was greater than we ever thought, she also demonstrates that most of the things we were previously told about them were either false or misleading.

First, the “S”-word. The Wikipedia article on “Slavery in Britain” discusses the slaving voyages of the mariner John Hawkins down the West African coast in the 1560s, and adds: “Britain soon became the leader in the Atlantic slave trade.” But no, it didn’t, unless “soon” means “in the following century”. Hawkins’s three voyages were a one-off – or rather a three-off – and there was no serious attempt to repeat them until the 1640s.

No moor a slave: detail of Jan Mostaert’s Portrait of a Moor, c 1525-30

No moor a slave: detail of Jan Mostaert’s Portrait of a Moor, c 1525-30

Again, as every schoolchild knows (if their school has downloaded the Guardian Teacher Network’s “Black History of Britain Timeline”), the first “slaves” were brought to Britain in 1555. Why exactly five high-status Africans were brought here then is not clear – possibly to learn English, in order to go back and facilitate trade. But the important thing, unmentioned in the Timeline, is that English law did not recognize slavery.

A court decreed in 1569 that “England has too pure an Air for Slaves to breathe in”; any former slave who settled here was treated as a free person. Miranda Kaufmann has found records of hundreds of Africans living in England in this period; some were independent, some were servants, but none was a slave.

The idea of black servants may ring a bell with anyone who has looked at Renaissance paintings set in the households of European rulers and aristocrats. Wasn’t it à la mode to have a black page or serving-girl, who would be dressed up in fine clothes as a sort of exotic pet or fashion accessory? Yes, that did happen, though there was nothing unusual about putting good clothes on some categories of personal servants. But the idea that this was the typical employment of an African in England is, as Kaufmann insists, plain wrong. Almost all the ones who were servants had normal jobs – cooks, gardeners, laundrywomen, and so on.

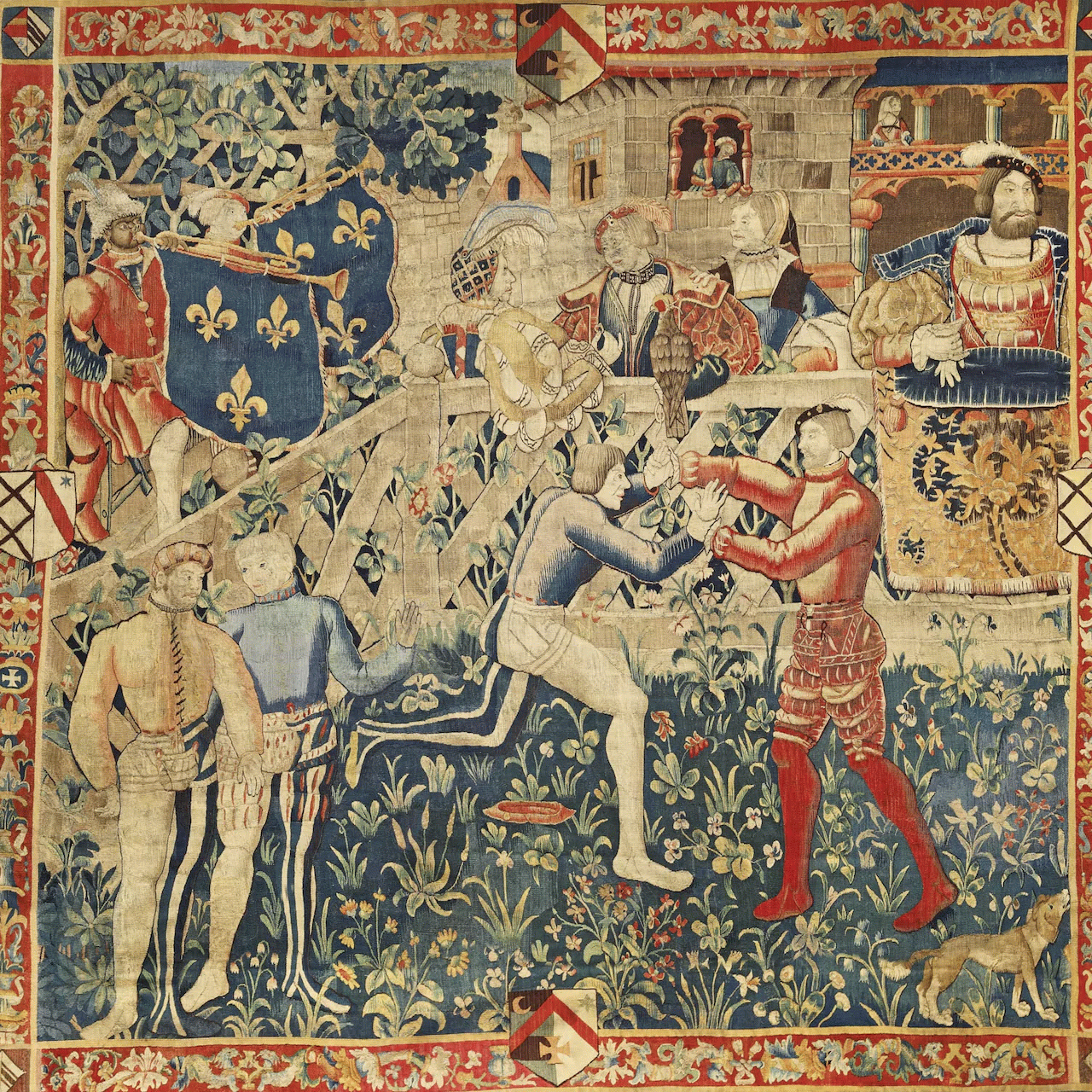

The Meeting of Kings Henry VIII and King Francis I (Tapestry), c 1520

The Meeting of Kings Henry VIII and King Francis I (Tapestry), c 1520

And what about the ones who were not? In many cases the records just don’t tell us: we know that “Thomas Bull, niger” was buried in Eydon, Northants, in 1545 and “Galatia the black negra” in Stowell, Somerset, in 1605, but not what they had been doing there. (The “N”-words, by the way, were normal descriptive terms, from Latin and Spanish, and as neutral as “black” today.)

Africans were not confined to ports and trading centers; Kaufmann has found them in villages far inland, from Dorset to Cambridgeshire, presumably doing the same villagey things that other villagers did. But in some cases we do know enough, just enough, to get a sense of an individual’s life story.

The book is structured around 10 people with very different careers, including a trumpeter at the court of Henry VIII, a salvage diver employed on the wreck of the Mary Rose, a silk weaver in London, a sailor who went halfway around the world with Francis Drake, a prostitute famous for her fine complexion, and an independent “single woman” who kept a cow and sold butter in a Gloucestershire village.

Only in very rare cases – the sailor, for example – do we have any narrative sources that mention these people. Mostly it is a matter of piecing together their lives and activities from a few surviving documents such as household accounts, legal papers, and wills.

T the industry and skill with which Miranda Kaufmann has hunted for these sources and teased out their meanings are exemplary. But it gets even better than that. Just telling us what is in the documents would not have made a book. Kaufmann’s greatest skill is her ability to fill in the background on every topic that arises, from piracy to silk-weaving to brothels to Anglo-Moroccan diplomacy.

T the industry and skill with which Miranda Kaufmann has hunted for these sources and teased out their meanings are exemplary. But it gets even better than that. Just telling us what is in the documents would not have made a book. Kaufmann’s greatest skill is her ability to fill in the background on every topic that arises, from piracy to silk-weaving to brothels to Anglo-Moroccan diplomacy.

In the hands of a lesser writer, this would be mere padding with secondary material, but she investigates every subject in the same depth. I liked the detailed account of what Elizabethan sailors wore to keep dry, and could not resist, apropos of the Gloucestershire milk-lady, the list of the most popular names given to Elizabethan cows, beginning with “Gentle” and “Brown Snout”.

What’s not to like? One thing: strange little invented passages at the start of every chapter, as if we could not get interested in these people without having them presented, however briefly, like characters in a novel. But that is a small price to pay for a fascinating book, which brings a sadly neglected part of our history to life, and grinds no ideological axes in the process.