In Guyana, the former British colony on the western border of Suriname, a small island is located exactly where two rivers meet. There are the remains of a fort that once overlooked the mighty estuary. Visitors to the ruin like to be photographed next to a sign that reads ‘Fort Kyk-over-al, 1616’.

If you have a chat with the locals, you will invariably be reminded of a large, old tree that grows on the waterfront. He is called ‘the Dutch tree’ because it was planted by the Dutch centuries ago.

The country’s third-largest city is still called ‘New Amsterdam’, and until recently some small communities in Guyana still spoke ‘Dutch Berbice’, a creole language based on the Zeeland dialect.

In the Dutch village of Voorschoten, you can visit the monumental country town ‘Berbice’, a building that a wealthy lawyer built with the money he made on a thriving sugar plantation in Berbice. And anyone who knows the phrase “go all the way to the Barrebiesjes” knows that this means that you go to the devil, and maybe even get killed.

The proverb recalls the thorny position the Dutch once found themselves in: in a murderous climate, victim of deadly diseases and cornered by enraged enslaved people who reclaimed their freedom.

Two hundred years of Dutch presence

The history of the Barrebiesjes, or actually Berbice, is relatively unknown in the Netherlands. But the country now called Guyana has been in Dutch hands for almost two hundred years.

The colonized area consisted of three parts, named after the three major rivers that flow from the interior into the Atlantic Ocean: the Essequibo, the Demerary, and the Berbice. Each part had its own Dutch governor. The area was part of what was called the ‘Wild Coast’ and Suriname.

Enslaved Africans grew coffee, cotton, and sugar for the Dutch masters, initially mainly in the interior along the banks of the rivers, but later also increasingly in coastal areas.

Through the success stories of Europe’s colonial past and the prevailing idea that the moral resistance to slavery came from a progressive, enlightened European corner, you might think that enslaved people carried their fates for centuries.

In Berbice, the first-ever organized slave revolt took place on the American continent in 1763

However, nothing could be further from the truth. There were many forms of resistance and resistance, and the African people of the colonies have thought from the beginning about new ways of living together in the countries in which they had ended up.

The history of Berbice gives a strong example of this: in 1763, the first organized slave revolt took place on the American continent. The leader of the resistance negotiated with the Dutch governor about ‘sharing’ the colony.

That leader was known as Cuffy, which came from Kofi – a still common name in Ghana, which means ‘born on Friday’. Just because Cuffy led the first organized slave revolt on the American continent, he deserves a place in the series Hidden History.

Constant unrest in the colony

Constant unrest in the colony

The rebellion didn’t fall from the sky. Due to the explosive growth of the number of plantations along the fertile river banks, the unrest grew. There was money to be made here, that was clear, but it required a lot of work. More and more enslaved Africans were being brought in. The ratio between white and black grew extremely skewed: in 1760, the colony had 350 Europeans and 4,000 Africans.

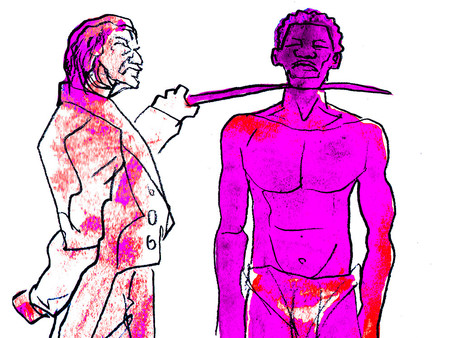

Knowing they were far outnumbered frightened the white supremacists. They acted with a hard hand. Those who, as enslaved, did not meet the strict requirements of the overseers, could expect ever more cruel punishments.

Many enslaved people were looking for ways to escape. Some fled to Suriname, where they disappeared in the interior and joined the maroons, In this story, you can read more about the maroons. the slaves who had already fled to Suriname, who started their own societies, far away from the world of the settlers.

This ‘marronage’ was a major problem for the colonizer because it meant a considerable loss of labor. As soon as there was an outbreak, patrols hunted the runaway men and women – and when they were found, the punishments were extremely severe, as a deterrent to the others.

However, this approach only increased discontent. After a rebellion on the Goodland and Good Fortune plantation was violently crushed in 1762, with the death of thirty enslaved Africans as a result, buzzed and boiled it with restrained anger among the plantation population of Berbice. The cruelty of the plantation owners on the Wild Coast even led to concerns among their white contemporaries.

“These people use you in your service, and most of you act tougher and harder with them when they deal with their stupid cattle,” wrote the missionary Jan Willem Kals in 1756 in Useful and necessary converts of the Gentiles in Suriname and Berbice.

“Is it any wonder these people are running away? And then come together in the woods, where you have all kinds of consultations to get paid at any time, what you have done to themselves or their pre-presidents?”

Kals was right. Tensions increased further in the months following the uprising on Goodland and Good Fortune – only to eventually lead to a violent eruption.

The uprising of 1763

In the early morning of February 23, 1763, the enslaved people moved from the Magdalenenburg plantation to the fields. It seemed like a day like any other, until, just before they were to go to work, the enslaved threw themselves at the white overseer and killed him.

What the specific reason was is not known, but the original French vernesobre family that owned the Magdalenenburg plantation was known for treating enslaved people harshly. The governor of Essequibo, Laurens Storm of ‘s Gravesande, called the family “worse than barbarians.”

After killing the superintendent, the Magdaleneians – reportedly 73 men and women – rushed to the large house and gathered all the firearms that were there. Anxious, but also excited, they went to the adjacent plantation Of La Providence to convince the enslaved there to join them and escape together.

The Magdalene people probably never intended to attack colonial rule: they simply sought the freedom to live their own lives.

Most dared not: life outside the plantations was uncertain, and the South American wilderness was almost impenetrable. Eventually, a dozen joined the group. The rest were left behind at La Providence, probably afraid of the repercussions of the governor of Berbice, Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim.

When he learned of the uprising, he did indeed send reinforcements to Magdalenenburg. The insurgents had already fled and had entrenched themselves in the jungle along the Corantijn, the border river with Suriname.

The Magdalene people probably never intended to attack colonial rule. They simply sought the freedom to live a life of their own. Yet their escape probably led to a much larger and more profound resistance that would be the first organized slave rebellion in the history of the Caribbean, later known as the ‘Berbice Slave Rebellion’.

Cuffy, leader of the enslaved

Cuffy, leader of the enslaved

At the time of the Magdalenenburg uprising, lilienburg, a plantation a little downstream on the River Canje, was home to a young African which was called Cuffy (or: Kofi). He had ended up in Berbice after he was allegedly sold as a child to human traffickers in West Africa.

When news of the magdalenenburg uprising reached him, Cuffy was already preparing his own uprising on Lilienburg. He was a trained fighter and enjoyed the trust of the men and women who wanted to shed the yoke of the slave drivers.

The success of the Magdalenenburgers was the starting point for the spread of a colony-wide resistance, and under Cuffy’s leadership, the group seemed unstoppable. Lilienburg was quickly taken. Cuffy armed his people with the weapons they looted in the superintendent’s house.

Then they descended to the adjacent plantation, and the one next door, and the one next door. With each plantation taken, more weapons were captured, and more people joined the resistance. Houses and fields were set on fire, whites who resisted were killed. Slowly but surely, the resistance group descended along the Berbice, until they arrived at the colony’s capital, Fort Nassau.

Death on Plantage Peereboom

Fleeing the violence, the white population of Berbice had sought refuge in the neighboring colony of Demerera. Those who did not get that far hid on the governorate plantation Peereboom – one of the few places where the vigilante was still somewhat intact.

Forty men and twenty women and children were holed up in the plantation’s sturdy stone house on 3 March 1763, when Peereboom was attacked by 500 former enslaved people.

Attempts at consultation failed. The rebels showed no mercy. The roof of the plantation house was set on fire, and every European who fled the house was shot. Eyewitnesses later said the rebels would have several people hated white overseer would even live skinned.

Years later, the wildest stories would circulate about how bloodthirsty the vengeful revenge of the enslaved was and how they now applied the punishments their own people had suffered to the whites.

Centuries later, in 1955, the Guyanese writer Edgar Mittelholzer wrote a novel about a Dutch plantation owner who was murdered during the slave uprising of 1763. In the story, his soul cannot find peace until he gets a Christian funeral.

Also in the distant Netherlands, the uprising was reported with horror. In May 1763, the Sincere Haerlemsche Courant brought the ‘sad tiding’ that after the house on plantation Peereboom was overrun by the rebels, ‘the Dutch Governor, and zyne Familie, neither Benevens nor 22 Familien, were murdered by them.”

With a force of less than thirty soldiers, the governor was powerless to confront the resistance, which now has about 3,000 men.

This probably meant the families of the other plantations, because governor Van Hoogenheim was not on the Peereboom plantation at that time. He was certainly alive, although he must have lost his nerve by now.

With a force of fewer than thirty soldiers, he was powerless against the resistance, which now has about 3,000 men. In addition, a diphtheria epidemic had broken out among the Dutch, a disease to which Van Hoogenheim had previously his pregnant wife had lost.

It was clear to Van Hoogenheim that Berbice was lost. In order not to let the only solid structure that the colony was rich in fall into the hands of the Africans, he decided to set Fort Nassau on fire.

The governor fled with the remaining Europeans to Saint Andries, a piece of the savannah at the mouth of the Berbice. And while the others begged to leave the Inferno of Berbice, Van Hoogenheim decided that he would not give up the colony so easily.

Perhaps he feared that if one colony was lost to enslaved people, the others would follow inexorably. If only he held out long enough, I’m sure there would be reinforcements.

The new governor of Berbice

For Cuffy, the destruction of Fort Nassau was a sign that the Dutch had lost. He then proclaimed himself the new governor of Berbice, pointing out his right-hand man Akara to maintain discipline in the group and to provide supplies and other necessities.

Now that he had Berbice in his hands, and the Dutch were virtually defeated, Cuffy wanted to end the war. He reached out to Van Hoogenheim and wrote him a letter, The Guyana Story. From Earliest Times to Independence (2013), What is striking is the respect with which Cuffy addressed Van Hoogenheim, while at the same time he left no doubt as to who was now at the head of the colony:

“Cuffy, Governor of the and Captain Akara send greetings and inform Your Excellency that they are not seeking war. But if Your Excellency wants war, the Negroes are willing to do so.”

Cuffy pointed out the reason for the uprising: the poor treatment by the plantation owners. He named the culprits by name: “Barkey and his servant De Graff, Schook, Dell, Van Lentzing and Frederick Betgen, but especially Mr. Barkey and his servant, De Graff, are the main causes of the riots in Berbice. The Governor (Cuffy) witnessed it when it happened, and he was very angry about it.’

Cuffy continued with a clear negotiation. He was willing to talk, and as long as Van Hoogenheim was open to it, he had nothing to fear from the Africans:

“The Governor of Berbice asks Your Excellency to come and speak to him; Don’t be afraid. But if you don’t come, we will fight until there is no Christian left in Berbice.’

Finally, Cuffy Van Hoogenheim offered an agreement: not war, but a division of the country. And, most importantly, an end to slavery (at least, for Cuffy and his people).

“The Governor will bestow half of Berbice upon Your Excellency, and all Negroes will retreat high along the rivers, but do not think that they will remain slaves. The Negroes that Your Excellency has on his ships – they can remain slaves.”

Divisions after the uprising

The latest addition – ‘they can remain slaves’ – outlines the complex relationship that the eighteenth-century people had with the slavery system. The resistance to slavery had countless faces: there were those who forcefully took back their freedom, and there were those who fled and completely escaped the violent world of the settlers.

But there were also those who cooperated with the white overseers, often under duress, and went on a hunt to bring back runaway enslaved people. An example of this kind of people traitors were the Redi Musu in Suriname, The Surinamese Ministry of Defense wrote about the Redi Musu. named after the red headgear they wore so that the white soldiers didn’t confuse them with hostile Africans.

In a book by Eveline St. Nicholas that the Rijksmuseum stands a painful example of how resistance could be broken from within through betrayal.

In 1862, a century after the uprising in Berbice, there was great unrest among the enslaved in Suriname. In secret meetings, Nickerie’s enslaved Colin (just across the border with Berbice) told compellingly about the need for resistance and the impending liberation of black men.

Colin was popular, which of course was an eyesore for the white masters. Eventually, he was betrayed by George, another enslaved, and arrested during one of the secret meetings.

The traitor received a badge with the inscription: ‘To the Slave George of the pl. Mr. Leasowes. For proven allegiance to the Lawful Authority in 1863’. Colin was sentenced to death and disappeared into oblivion. George’s badge is still in the Rijksmuseum.

Cuffy wouldn’t end up losing his battle with treason. However, it became clear that the enslaved Africans were divided on how best to wage war – and who was ultimately in charge of that collection of people who, with the other means of a common enemy, had nothing in common.

Cuffy the ‘house slave’

Cuffy was an outspoken opponent of war and proposed a division of the country with the whites, but many of his supporters thought otherwise.

An important part of the internal resistance came from the ‘field slaves’, the enslaved who did the heavy lifting on the plantations. They distrusted Cuffy because he was one of the rare ‘house slaves’; someone who did his work in the plantation owner’s house and was often literally closer to the white oppressor.

Was that perhaps why Cuffy was talking about peace with the Europeans? And so he didn’t want a war, but did he propose to divide the country among himself?

Van Hoogenheim got wind of cuffy’s discontent and deliberately did not answer Cuffy’s offer, in the hope that outside help would come. Patience among the ranks of the resistance ran out, and without the leader’s permission, several members of the resistance carried out attacks on the remaining plantations still in the hands of the Dutch.

Cuffy wrote another letter to Van Hoogenheim in which he demanded freedom for the enslaved. The Leeuwarder Courant of 9 July 1763 reported on this under ‘military news’:

‘With letters from Suriname’, the message began, the news had come that on 14 May ‘the Negroes had done an Attacque from 7 to 1 o’clock, but had to withdraw. “On the next day, the Head of the Muytelingen had a preliminary strike of Vreede made to the Governor, provided that all the Rebels are declared, and that they were to be given half of the Colony, to live there; but it was sustained that this was not done in any way.

The Netherlands apparently had no intention of sharing a colony with enslaved Africans

The Netherlands apparently had no intention of sharing a colony with enslaved Africans. The systematic repression resulted in cheap labor and therefore large profits. Dismissing them from slavery, as Cuffy demanded, was an idea that provoked scorn and outrage in 1763.

Van Hoogenheim’s tactic of waiting for outside help proved successful. In the resistance camp, discontent grew over Cuffy’s peace negotiations. There was a new leader, Atta, who joined more and more Africans.

After a confrontation between Cuffy’s supporters and Atta’s, the latter won. Cuffy, disillusioned, committed suicide. The resistance was now definitively led by Atta.

The end of the uprising

In the meantime, the cornered Dutchmen received reinforcement from the governor in Suriname. Help also came from the island of Saint Eustatius. It came to a number of battles with the resistance under Atta, in which the Africans barely held their own.

When in December 1763 a Dutch fleet with some 600 soldiers docked at the mouth of the Berbice, this was the beginning of the end for the resistance. In a series of battles, the soldiers drove the Africans off the plantations, and in the summer of 1764, the entire colony was recaptured.

In total, more than 1,800 Africans had died. Atta was arrested and sentenced to death with other leaders of the resistance. In three rounds of execution, the Dutch killed 119 rebels. Most died of the gallows, some of them were frayed and 24 of them were burned alive, seven of whom were killed by ‘small fire’. as slowly as possible.

For Atta, who was considered the most callous of the rebels, the most derelict death sentence could possibly be imagined. So cruel, I’m don’t really want to repeat.

Pride and strength

In retrospect, the pride and strength of the Africans were praised. Not only by the black population of Berbice, but also by white witnesses who told that ‘not only Atta, who was tortured for several hours, but also almost all the other enslaved people ‘without shouting or groaning theirs suffered punishments with courage and fortitude. In it, they showed ‘truly more dignity than some of those who have come to the execution.

The deaths of Atta and Cuffy, and of the 1,800 others who had joined the African resistance, marked the end of the first organized slave revolt on the American continent. For almost a year, much of the colony had been in the hands of the Africans.

When the Netherlands restored its position in Berbice, newly enslaved people were quickly introduced, and the plantation owners became the colonial order of the day. Berbice, Essequibo, and Demerara were eventually lost to England and christened British Guiana.

After Guyana’s independence in 1966, February 23, the day the great slave revolt began, was declared Guyana’s national holiday. On that day, Cuffy is also honored every year as leader of the resistance and Guyana’s national hero.

The darkest stories are Dutch

The Dutch tree from the beginning of this story is not the only tree in Guyana with Dutch roots. In several places in the country are ‘Dutchman trees’; trees to which strong, dark forces are attributed.

An old Guyanese ghost story tells how the Dutch settlers had a habit of hiding their wealth among the roots of these trees centuries ago. In order not to betray the place, the enslaved who had to dig the hole for the treasure were murdered and buried together with the treasure. Since then, it is said, the Dutchman trees in Guyana have been plagued by the restless souls of deceased Dutchmen.

It is because of the eventful, dark history that the country shares with the Netherlands, that the very spirits in the Dutchman trees are considered the evilest and depraved of all the ghost stories that the country is rich in.

The ‘Berbice Slave Uprising’ ultimately failed, but still had major consequences. The uprising showed what organized resistance to colonial violence was capable of.

Today, historians see the resistance as a precursor and inspiration for the Haitian Revolution of 1791. This revolution is about the next episode of Hidden History, because it has been of invaluable importance to the identity of the Caribbean, and because it shows the great connection of world histories, from the Enlightenment as an impetus to think about universal human rights, to the repercussions for black states that claim their independence.

Correction August 6, 2018: An earlier version stated in the first paragraph that the fort Look-over-al came from 1816. That must be 1616. It also said that Guyana became independent in 1970, which must be 1966. Both years have been adapted.