Born into slavery in Delaware on November 2, 1857, Albert Calvin Jackson emerged as a trailblazer against immense odds, becoming Toronto’s first Black letter carrier and one of the exceedingly rare people of color appointed to a civil service position in 19th-century Canada. As the youngest of nine children in a family fractured by the brutal machinery of American enslavement, Jackson’s early life was marked by profound loss and resilience. His father, John Jackson, a free-born blacksmith, had managed to keep his enslaved wife, Ann Maria, and their children together by paying their enslaver, but this fragile arrangement was shattered when two of Albert’s oldest brothers, James and Richard, were sold away. Devastated, John died of grief in a local almshouse, leaving Ann Maria to fear the same fate for her remaining seven children, including the toddler Albert.

Determined to secure freedom for her family, Ann Maria orchestrated a daring escape in 1858, leveraging the clandestine network of the Underground Railroad. With the aid of Quaker abolitionist Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware, they were smuggled by carriage to Pennsylvania, where African American abolitionist William Still arranged their crossing into Canada West (now Ontario). Arriving in St. Catharines by late November, the Jacksons briefly found refuge with Thornton and Lucie Blackburn—a Black couple who had themselves fled enslavement in Kentucky and later established Toronto’s first taxi business. The family soon relocated to Toronto’s St. John’s Ward, a bustling working-class enclave north of Osgoode Hall teeming with immigrants and freedom seekers. To survive, Ann Maria and her daughters took up grueling work in laundry and waitering, scraping together enough to send Albert to local schools for an education that would prove pivotal. Remarkably, Jackson’s sold brothers, James Henry and Richard M., later reunited with the family in Toronto, where they established successful barber shops and became pillars of the Black community.

By his early twenties, having completed his schooling, Jackson set his sights on stable employment within Canada’s burgeoning federal postal system. His perseverance paid off on May 12, 1882, when he was hired as the inaugural Black letter carrier for Royal Mail Canada—a groundbreaking appointment amid widespread exclusion of African Canadians from public roles. Yet, triumph was swiftly eclipsed by bigotry. On his first day at the Toronto General Post Office—a stately four-story edifice on Toronto Street, operational from 1873 to 1958 and alive with horse-drawn carriages and pedestrian bustle—white colleagues flatly refused to train him, citing “intense disgust” at working alongside a Black man. His supervisor, bowing to the pressure, demoted Jackson to the menial indoor task of hall porter, sweeping floors and tending doors in a humiliating sidelining.

Word of the injustice spread like wildfire through Toronto’s African Canadian community, igniting a fierce backlash. On May 29, 1882, a packed public meeting at Richmond Street Methodist Church—attended by Jackson’s own family members—gave birth to an advocacy committee determined to fight for his rights. Community leader George Washington Smith, a barber and vocal advocate, penned a scathing letter to the press decrying the racist sabotage and affirming Black capability when afforded equal chances. The uproar spilled into Toronto’s newspapers, fueling a vitriolic debate laced with pseudoscientific claims of racial inferiority and even street-level harassment against Jackson. Yet, this controversy proved a double-edged sword: it drew unlikely allies, including Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, who, eyeing Black voters’ sway in the looming federal election, intervened decisively. On May 30, Smith and four committee members met with Macdonald, who promptly ordered the Postmaster General to reinstate Jackson with full training.

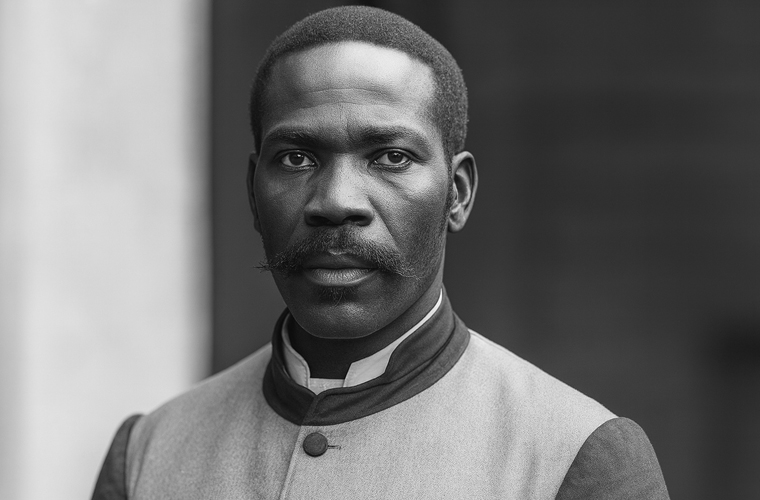

Vindicated, Jackson donned his uniform on June 2, 1882, and embarked on a 36-year tenure as a letter carrier, faithfully traversing the tree-lined streets of Harbord Village—a vibrant, evolving neighborhood of professors, laborers, and immigrants—delivering correspondence that knit the community together. A circa 1892 group portrait by Kennedy & Bell captures him among his fellow carriers, a quiet testament to his hard-won place. Amid ongoing undercurrents of prejudice, Jackson’s steadfast service symbolized quiet defiance, paving the way for future generations in civil service.

On a personal front, Jackson’s life blossomed into one of stability and legacy-building. In 1883, he married Henrietta Elizabeth Jones, a fellow descendant of Underground Railroad freedom seekers, and together they raised four sons: Alfred, Richard, Harold, and Bruce. The couple invested wisely, purchasing multiple homes in downtown Toronto; after Jackson’s death, Henrietta and their sons expanded their holdings in Harbord Village, contributing to the area’s economic vitality. Henrietta outlived her husband by four decades, passing at 99 in 1958, and the pair rest side by side in Toronto Necropolis Cemetery, their gravestone a poignant inscription: “In loving memory of Albert C. Jackson, Died Jan 14, 1918… Fell asleep in Jesus.”

Albert Jackson’s death on January 14, 1918, at age 60, closed a chapter but amplified his enduring impact. His story, emblematic of the over 30,000 freedom seekers who reshaped Canada, underscores the intertwined struggles for abolition and equity. In 2024, Parks Canada designated him a National Historic Person, honoring his role in challenging systemic racism and advancing employment equity for Black Canadians. Commemorations abound: a 2013 poster by the Canadian Union of Postal Workers; a Harbord Village laneway bearing his name; the 2015 doorstep play The Postman tracing his routes; a 2017 plaque at the former post office site; a 2019 Black History Month stamp from Canada Post; and, in 2022, the opening of the massive Albert Jackson Processing Centre in Scarborough—the nation’s largest mail-sorting hub. As his great-granddaughter Shawne Jackson-Troiano reflects, “Albert Jackson showed true strength and dignity while being persecuted… The most indelible legacy he has left us with is the importance of family and never backing down!” From the very site of the Toronto General Post Office, where he once collected his bundles amid the clatter of 19th-century commerce, Jackson’s footsteps echo as a beacon of perseverance.