As Brazil’s sugar economy expanded explosively in the 16th century, the nation’s Portuguese occupiers cultivated a system of plantations that became dependent upon the trafficking of African slaves. Treacherous overseas journeys from regions such as Congo saw hundreds of starved human beings, vulnerable to scurvy, smallpox, measles, and more, crammed into vessels for trips that lasted more than 30 days.

If the captives survived the voyage, which saw slaves launching themselves overboard rather than face what waited on Brazil’s shores, they navigated shifts of punishing physical work that clocked in at 12 to 16 hours daily. Many of them died within five years of having arrived in the camps. In the late 1500s, slaves began escaping Brazil’s brutalizing plantation labor and fleeing to the hilly northeast for the lush forested camouflage that the state of Pernambuco could afford them.

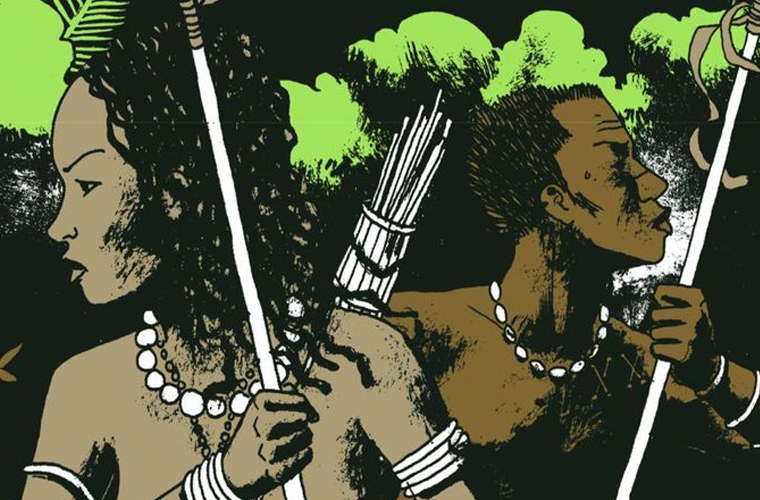

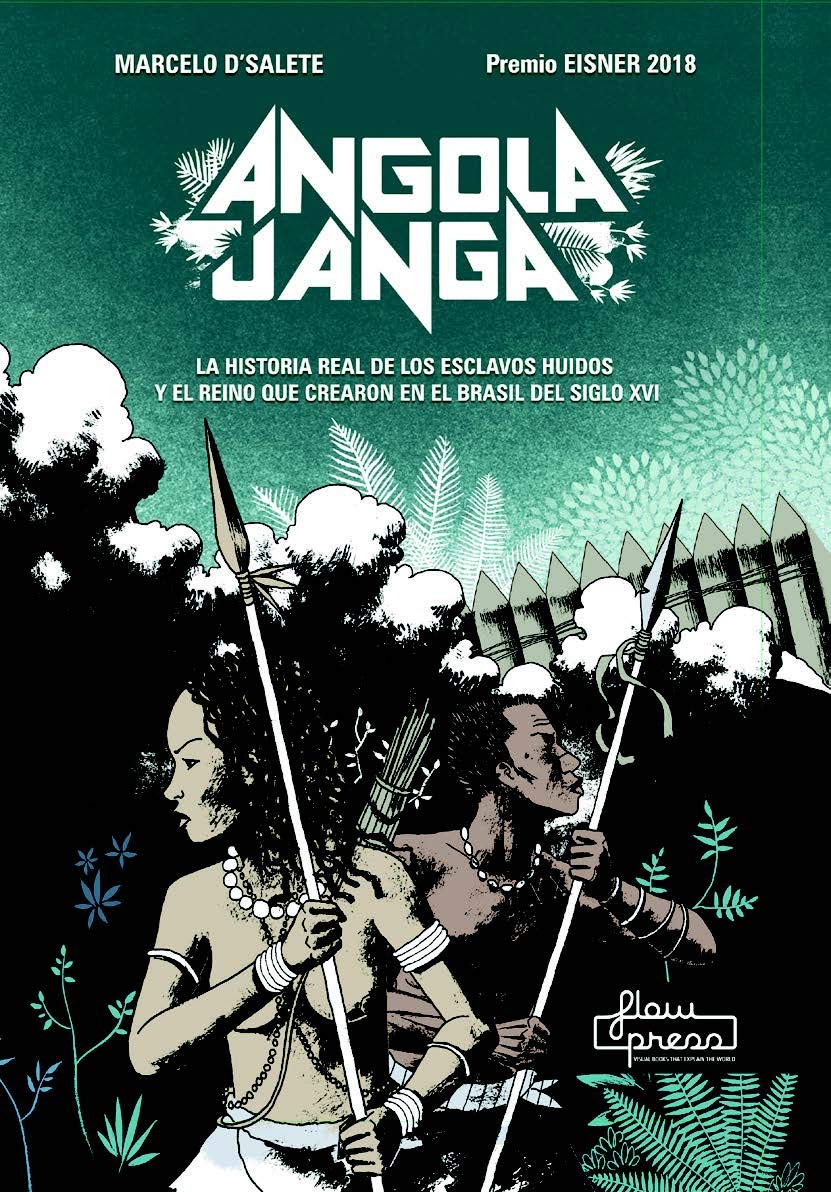

For a big graphic novel called “Angola Janga: Kingdom of Runaway Slaves,” Brazilian artist and writer Marcelo D’Salete mined historical texts about black resistance on sugar plantations during centuries of enslavement. To re-imagine the story of a real-life society of runaway slaves, he folded fictional elements into 11 years’ worth of research on an actual refuge that its inhabitants called “Angola Janga.” To everyone else, the assembly of more than a dozen individual settlements was known as Palmares, and it was huge.

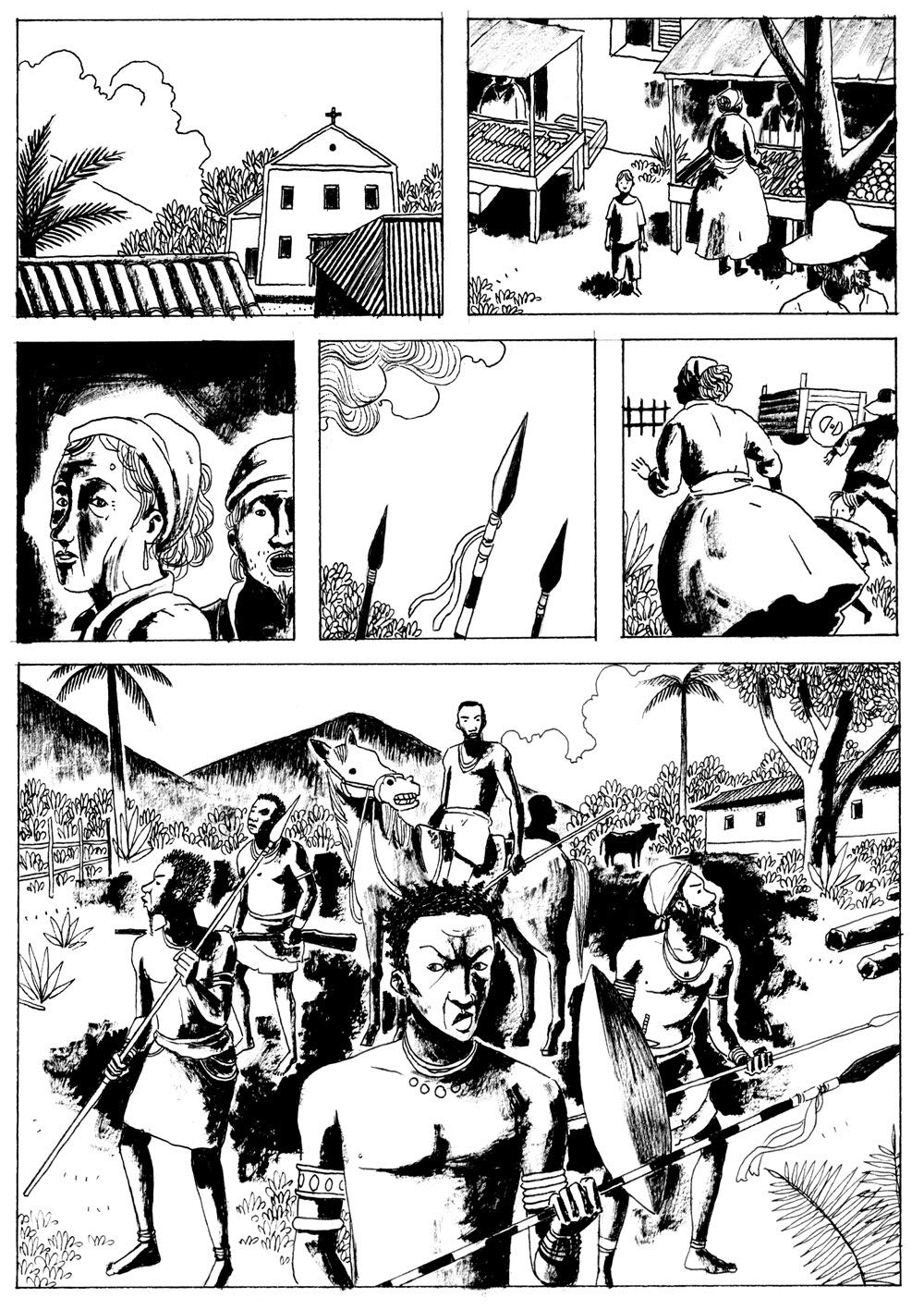

A page from Marcelo D’Salete’s graphic novel “Angola Janga: Kingdom of Runaway Slaves.”

A page from Marcelo D’Salete’s graphic novel “Angola Janga: Kingdom of Runaway Slaves.”

On textured cream-colored paper stock, D’Salete shapes in “Angola Janga” a possible history of these Palmaristas (the runaway slaves), who raised crops, bred chickens, and traded for goods with a neighboring Portuguese village. He renders the tropical wilderness in thin, brittle linework, while blotty sponged black ink fills out coarse tree bark and the shadows cast by leafy vegetation. Bloody skirmishes play out against stretches of impenetrably silhouetted trees. They’re bordered by swirling contour lines of clouds on the horizon.

Scarred by lashings and their plantation owners’ brands, the fugitive Soares and his malungo (or companion) Osenga, in “Angola Janga’s” first chapter seek safety in the Mocambo or, later, quilombos — Bantu terms for the individual settlements of runaways in the Pernambucan hills. They keep watch for the bounty hunters and tracking dogs on their trail.

Flashback panels have Soares hauling sugarcane stalks off the plantation before he and Osenga fled. In his Eisner Award-winning “Run for It: Stories of Slaves Who Fought for Their Freedom,” D’Salete shares similar sequences. Although seldom easy to look at, its masterfully drawn pages articulate the harrowing conditions of plantation life for captives, whereas “Angola Janga” is almost exclusively staged in Palmares.

The only chance for survival for slaves like D’Salete’s Soares and Osenga awaited in the quilombos of Palmares. But after a suspect peace accord strained relationships between escapees’ factions, the fugitives’ safety wasn’t merely threatened by attacks from Portuguese soldiers or scorned slave masters.

“Palmares did not refer to one single quilombo, but to a confederation of communities of various sizes scattered around the region,” write Lilia M. Schwarcz and Heloisa M. Starling in 2018’s “Brazil: A Biography.” “They were interconnected by pacts, but they conducted their own business affairs, were autonomous and chose their own leaders.”

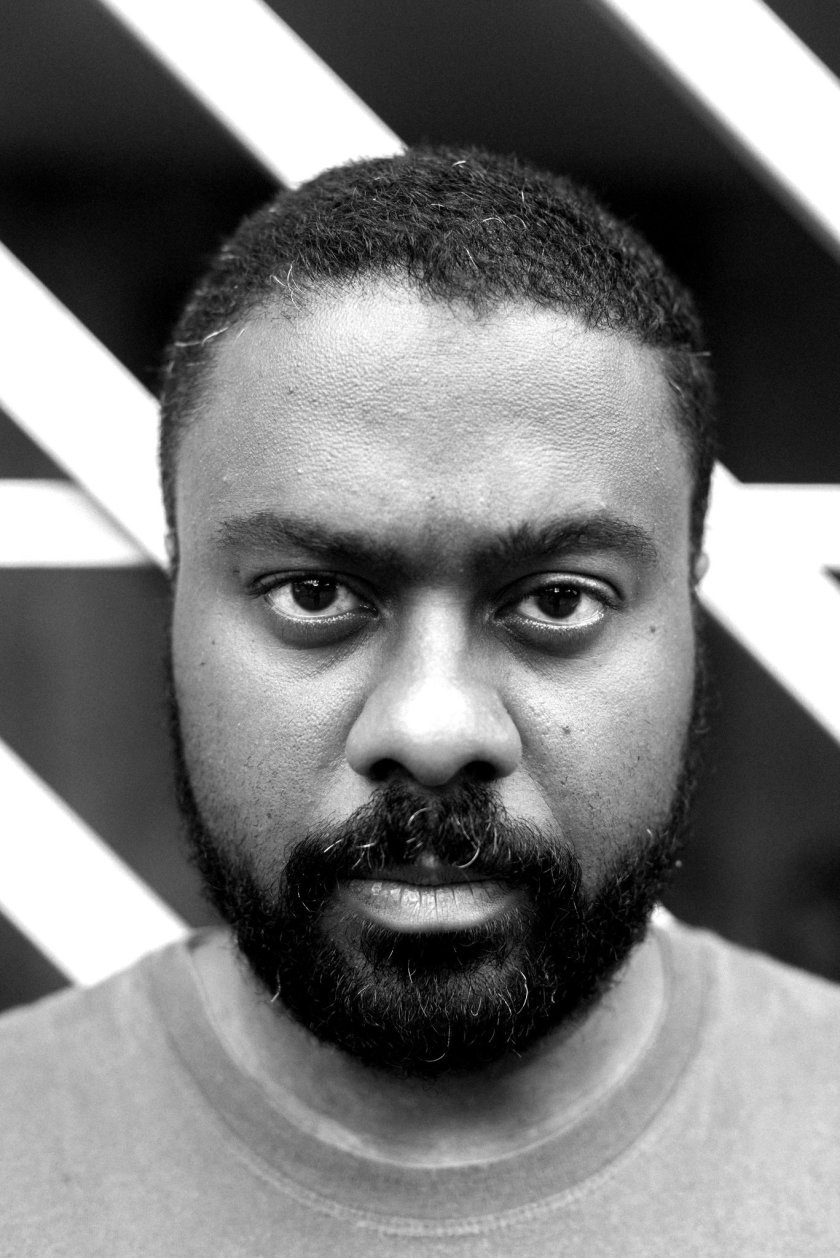

Marcelo D’Salete, author of “Angola Janga.”

Marcelo D’Salete, author of “Angola Janga.”

In his comic, D’Salete recounts the history of a peace treaty conceived by a quilombo leader and Pernambuco’s Portuguese governor in the 1670s. Per D’Salete, the agreement, which had the fugitives departing Palmares for land in the Cucaú Valley donated by Portuguese authorities, was a sham, “an effort to dissuade and divide the Palmaristas.” The “Brazil: A Biography” authors corroborate this, adding that the accord’s goal was to ultimately dissolve Palmares, “inaugurating the most violent period in the community’s history.”

In addition to battling the menacing armed white men who benefited from the peace accord, which severed the trade ties between runaways and local settlers, the fugitive slaves, as told in “Angola Janga,” differed on the terms of the treaty. Some slaves rightfully predicted they’d be “surrounded by whites” and essentially delivered to their enemy. Clashes ensue between settlements in D’Salete’s ashy-black panels. A spear-wielding Soares helps lead a revolt against the Cucaú settlement after seeing his future during hallucinatory encounters with Cuca, the refuge’s elderly medicine woman.

“Angola Janga” is a dense work — dialogue is minimal, D’Salete forgoes narration, and he doesn’t employ any aesthetic device to distinguish between flashbacks and real-time. A glossary, maps, and afterword support our comprehension of Palmares, while the art is unequivocal in communicating this history. Smudgy backdrops recall vintage graphic screenprints or storybooks, like insects, animals, and the attributes of the region’s delicate flora are drawn in affecting detail. But for each powerful accounting of Palmares’ geography, there is an unambiguous depiction of a runaway slave’s public punishment, or illustration of a child, Francisco, shell pressed to his ear, listening to the sea lapping against a ship stuffed with human cargo. Awe-inspiring or viciously ugly, it’s all part of D’Salete’s suggested history of Palmares, the capital settlement of which was destroyed by the Portuguese in 1694.

A page from Marcelo D’Salete’s graphic novel “Angola Janga: Kingdom of Runaway Slaves.”

A page from Marcelo D’Salete’s graphic novel “Angola Janga: Kingdom of Runaway Slaves.”

Approximately 50,000 slaves had arrived on Brazilian shores by the dawn of the 17th century. They were hauled into forced labor in gold mines, to harvest sugar in the sun, or to bake in their own skin over scalding cauldrons in boiling houses, where raw sugarcane was processed. When Brazil’s leaders finally abolished slavery nearly 300 years later— the last country to do so — between four and five million people had been trafficked in from Africa. New arrivals were publicly whipped to ensure subordination, raped on sugar mill floorsby camp masters, and if they escaped to the hills and were recaptured, they were mutilated or decapitated before big crowds.

D’Salete — who has recognized comics as integral to building his literacy skills — cites those who have come before him to share tales of Brazil’s massive system of slavery, a blueprint for how it would later function in France, Spain, and elsewhere. Most of us, however, are unfamiliar with this important story.