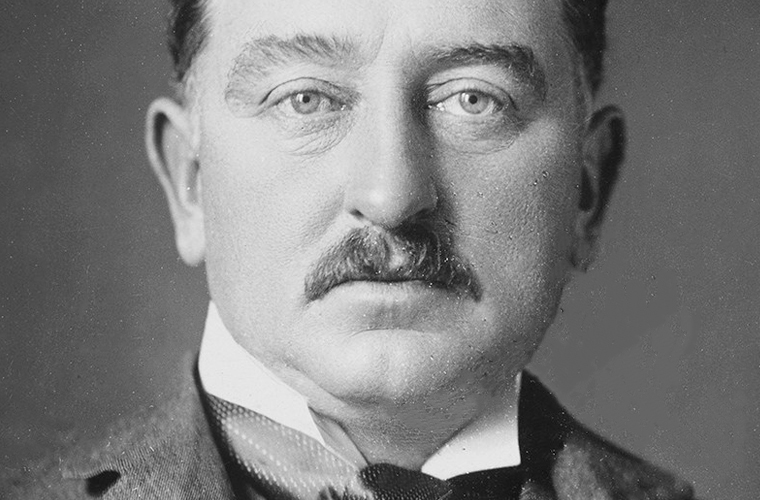

The English businessman and financier Cecil Rhodes founded the modern diamond industry and controlled the British South Africa Company, which acquired Rhodesia and Zambia as British territories. He was also a noted philanthropist (working for a charity) and founded the Rhodes scholarships.

Cecil John Rhodes was born on July 5, 1853, at Bishop’s Stortford, England, one of nine sons of the parish vicar (priest). While his brothers were sent off to attend better schools, Cecil’s poor health forced him to stay at home and attend the local grammar school. Instead of attending college, sixteen-year-old Cecil was sent to South Africa to work on a cotton farm. Arriving in October 1870, he grew cotton with his brother Herbert in Natal, South Africa, a harsh environment. Soon the brothers learned that growing cotton was no way to build a fortune and by 1871 “diamond fever” was sweeping the region with promises of fame and fortune. The two brothers soon left Natal for the newly developed diamond field at Kimberley, South Africa, an even less inviting environment.

In the 1870s Rhodes laid the foundation for his later massive fortune by working in an open-pit mine where he personally supervised his workers and even sorted diamonds himself. The hard work would pay off as Rhodes developed a moderate fortune by investing in diamond claims, initiating mining techniques, and in 1880 forming the De Beers Mining Company. In 1873 Rhodes returned to England to attend Oxford University. During his education, Rhodes split his time between South Africa and Oxford, where he did not fit in socially but finally earned a bachelor of arts degree in 1881.

During the mid-1870s, Rhodes spent six months alone, wandering the unsettled plains of Transvaal, South Africa. There, he developed his philosophies on British Imperialism, where the British Empire rules over its foreign colonies. These philosophies consisted of a “dream” where a brotherhood of elite Anglo-Saxons (whites) would occupy all of Africa, the Holy Land in the Middle East, and other parts of the world. After a serious heart attack in 1877, Rhodes revealed his ideas of British Imperialism when he made his first will. In it, Rhodes called for the settlement of his as-yet unearned fortune to found a secret society that would extend British rule throughout the world and colonize most parts of it with British settlers, leading to the “ultimate recovery of the United States of America” by the British Empire.

From 1880 to 1895 Rhodes’s star rose steadily. Basic to this rise was his successful struggle to take control of the rival diamond interests of Barnie Barnato, with whom he partnered in 1888 to form De Beers Consolidated Mines, a company whose extraordinary powers led to acquiring lands for the purpose of extending the British Empire. With his brother Frank, he also formed Goldfields of South Africa, with several large mines in the Transvaal.

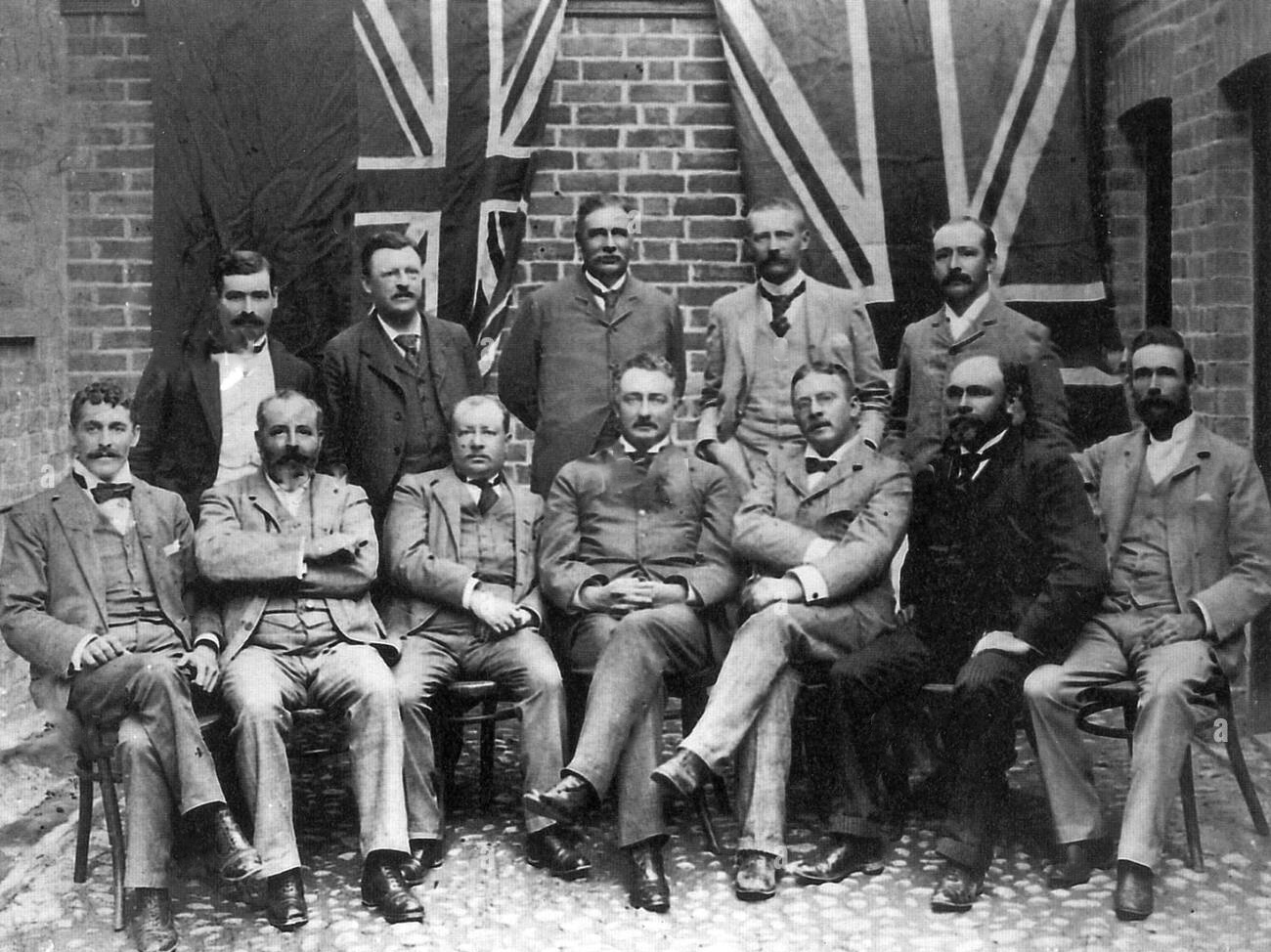

During this same time, Rhodes built a career in politics. He was elected to the Cape Parliament in 1880, the governing body of South Africa. In Parliament, Rhodes succeeded in focusing attention on the Transvaal and German expansion so as to secure British control of Bechuanaland by 1885. In 1888 Rhodes secured mining grants from Lobengula, King of the Ndebele, which by highly stretched interpretations gave Rhodes a claim to what became Rhodesia. In 1889 Rhodes persuaded the British government to grant a charter (authority from the British throne) to form the British South Africa Company, which in 1890 put white settlers into Lobengula’s territories and founded Salisbury and other towns. This sparked conflict with the Ndebele, but they were crushed by British forces in the war of 1893.

By this time Rhodes controlled the politics of Britain’s Cape Colony. In July 1890 he became premier of the Cape with the support of the English-speaking white and nonwhite voters and the Afrikaners (descendants of the Dutch settlers of South Africa). Rhodes won their support by creating a “Bond” where some twenty-five thousand shares of the British South Africa Company were distributed among them. His policy was to aim for the creation of a South African federation (union of states) under the British flag, and he gained the trust of the Afrikaners by restricting the Africans’ educational and property qualifications in 1892 and setting up a new system of “native administration” in 1894.

At the end of 1895, Rhodes’s fortunes took a disastrous turn. In poor health and anxious to hurry his dream of a South African federation, he organized a plot against the Boer government of the Transvaal, which was run by the Dutch settlers. Through his mining company, arms and ammunition were smuggled into Johannesburg, South Africa, to be used for a revolution by “outlanders,” mainly British. A strip of land on the borders of the Transvaal was awarded to the chartered company by Joseph Chamberlain (1836–1914), the British colonial secretary. Leander Jameson, the administrator of Rhodesia, was stationed there with company troops. The Johannesburg plotters did not rebel but Jameson, however, rode in on December 27, 1895, and was captured. As a result, Rhodes had to resign his premiership in January 1896. Thereafter he concentrated on developing Rhodesia and especially in extending the railway, which he dreamed would one day reach Cairo, Egypt.

When the Anglo-Boer War broke out in October 1899, Rhodes hurried to Kimberley, which the Boers surrounded a few days later. It was not relieved until February 16, 1900, during which time Rhodes had been active in organizing defense and sanitation. His health was worsened by the takeover, and after traveling in Europe he returned to the Cape in February 1902, where he died at Muizenberg, South Africa, on March 26.

In death, Rhodes’s fortune allowed him to leave behind a legacy that is still relevant today. Rhodes left six million pounds, most of which went to Oxford University to establish the Rhodes scholarships to provide places at Oxford for students from the United States, the British colonies, and Germany. The land was also left to eventually provide for a university in Rhodesia.