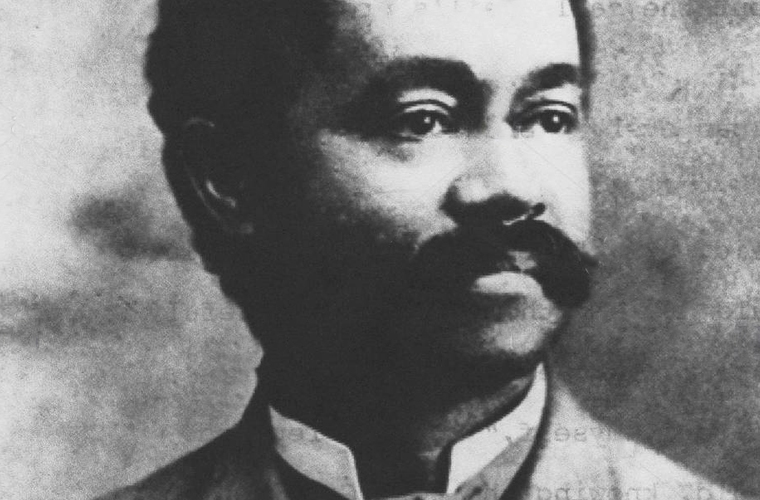

Charles Henry Turner, (born February 3, 1867, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.—died February 14, 1923, Chicago, Illinois), American behavioral scientist and early pioneer in the field of insect behavior. He is best known for his work showing that social insects can modify their behavior as a result of experience. Turner is also well known for his commitment to civil rights and for his attempts to overcome racial barriers in American academia.

Turner’s birthplace of Cincinnati had established a progressive reputation for African American opportunity and advancement. In 1886, after his graduation as class valedictorian from Gaines High School, he enrolled in the University of Cincinnati to pursue a B.S. degree in biology. Turner graduated in 1891; he remained at the University of Cincinnati and earned an M.S. degree, also in biology, the following year. In 1887 he married Leontine Troy.

Despite having an advanced degree and more than 20 publications to his credit, Turner found it difficult to find employment at a major U.S. university, possibly as a result of racism or his preference to work with young African American students. He held teaching positions at various schools, including Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University), a historically black college in Atlanta, from 1893 to 1905. He returned to school to earn a Ph.D. in zoology (magna cum laude) in 1907 from the University of Chicago. After Leontine died in 1895, Turner married Lillian Porter. In 1908 Turner finally settled in St. Louis, Missouri, as a science teacher at Sumner High School. He remained there until his retirement in 1922.

During his 33-year career, Turner published more than 70 papers, many of them written while he confronted numerous challenges, including restrictions on his access to laboratories and research libraries and restrictions on his time due to a heavy teaching load at Sumner. Furthermore, Turner received meager pay and was not given the opportunity to train research students at either the undergraduate or the graduate level. Despite these challenges, he published several morphological studies of vertebrates and invertebrates.

Turner also designed apparatuses (such as mazes for ants and cockroaches and colored disks and boxes for testing the visual abilities of honeybees), conducted naturalistic observations, and performed experiments on insect navigation, death feigning, and basic problems in invertebrate learning. Turner may have been the first to investigate Pavlovian conditioning in an invertebrate. In addition, he developed novel procedures to study pattern and color recognition in honeybees (Apis), and he discovered that cockroaches trained to avoid a dark chamber in one apparatus retained the behavior when transferred to a differently shaped apparatus. At the time, the study of insect behavior was dominated by 19th-century concepts of taxis and kinesis, in which social insects are seen to alter their behavior in specific responses to specific stimuli. Through his observations, Turner was able to establish that insects can modify their behavior as a result of experience.

Turner was one of the first behavioral scientists to pay close attention to the use of controls and variables in experiments. In particular, he was aware of the importance of variables called training variables, which influence performance. One such example of a training variable is the “intertrial interval,” which is the time that occurs between learning experiences. Reviews by Turner on invertebrate behavior appeared in such important publications as Psychological Bulletin and the Journal of Animal Behavior. In 1910 Turner was elected a member of the Academy of Sciences of St. Louis. The French naturalist Victor Cornetz later named the circling movements of ants returning to their nest tournoiement de Turner (“Turner circling”), a phenomenon based on one of Turner’s previous discoveries.

Turner maintained a lifelong commitment to civil rights, first publishing on this issue in 1897. As a leader of the civil rights movement in St. Louis, he passionately argued that only through education can the behavior of both black and white racists be changed. He suggested that racism could be studied within the framework of comparative psychology, and his animal research intimated the existence of two forms of racism. One form is based on an unconditioned response to the unfamiliar, whereas the other is based on principles of learning such as imitation.