If you rely on your GPS for directions, you can thank a mathematician whose little-known contributions to the mathematical modeling of the Earth recently earned her one of the U.S. Air Force’s highest honors: induction into the Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame! Dr. Gladys West, like the “human computers” at NASA who became famous with the book Hidden Figures, began her career by performing the complex hand calculations required before the computer age. However, her greatest accomplishment was the creation of an extremely detailed geodetic model of the Earth which became the foundation for the Global Positioning System. Although GPS is ubiquitous today, West says that at the moment, she wasn’t thinking about the future: “When you’re working every day, you’re not thinking, ‘What impact is this going to have on the world?’” she says. “You’re thinking, ‘I’ve got to get this right.'”

West was born on October 27, 1930, in a rural Virginia community of sharecroppers, but from an early age, she had the ambition to go beyond farm or factory work. “I thought at first I needed to go to the city. I thought that would get me out of the country and out of the fields,” she remembers. “But then as I got more educated, went into the higher grades, I learned that education was the thing to get me out.” West was valedictorian in her high school, which won her a scholarship to attend Virginia State College. There, she became one of only a handful of women studying mathematics. “You felt a little bit different,” she later reflected. “You didn’t quite fit in as you did in home economics.” West taught for several years after graduation and then accepted a position at the Naval Surface Warfare Center in Dahlgren, Virginia in 1956 — only the second black woman they had ever hired — analyzing data from satellites.

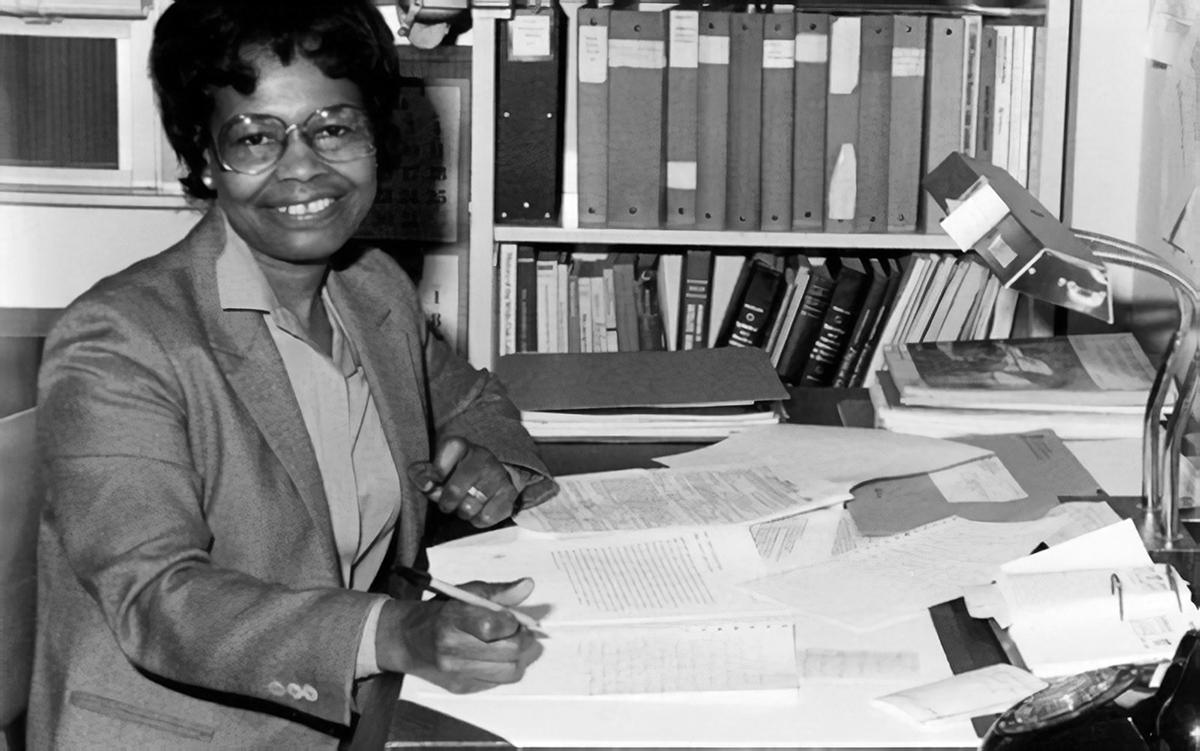

At first, that meant math on paper: “We would come in and sit at our desks and we would logic away, go through all the steps anyone would have to do to solve the mathematical problem.” But when computers entered the scene, it meant learning how to program — and being ready to catch the computers’ mistakes. “Nine times out of 10 they weren’t completely right,” she recalls, “so you had to analyze them and find out what was different to what you expected.” West was involved in an award-winning astronomical study in the early 1960s that showed how Pluto moved relative to Neptune, and her department head recommended her for a new role as project manager for the Seasat radar altimetry project, involving the first Earth-orbiting satellite that could remotely sense oceans.

The Seasat project became the jumping-off point for further satellite modeling of the globe, and from the mid-1970s through the 1980s, West worked on programming an IBM 7030 “Stretch” computer with increasingly refined algorithms. She was then able to create an extremely accurate geodetic Earth model, even factoring in details like gravitational and tidal forces that slightly change the Earth’s shape. This model would later become the foundation for the GPS satellite system, which is widely used today for countless applications from navigation to communication. However, after West retired from her post in 1998, her contributions to GPS were largely forgotten.

West wasn’t idle in retirement, although a stroke temporarily slowed her down. While she was recovering, she set a new goal: “all of a sudden, these words came into my head: ‘You can’t stay in the bed, you’ve got to get up from here and get your Ph.D.'” She became Dr. West in 2018, thanks to a remote studies program with Virginia Tech. Then, her story resurfaced after she wrote a short biography for an Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority event recognizing senior members of the group. Fellow member Gwen James, who had known West for fifteen years, was amazed to hear about her friend’s career, and quickly started spreading the word: “I think her story is amazing.”

In 2017, Captain Godfrey Weekes, then the commander of the Dahlgren Division, wrote an article for Black History Month about the “integral role” West played in the development of GPS, observing that “she rose through the ranks, worked on the satellite geodesy, and contributed to the accuracy of GPS and the measurement of satellite data. As Gladys West started her career as a mathematician at Dahlgren in 1956, she likely had no idea that her work would impact the world for decades to come.” On December 6, 2018, West was inducted into the U.S. Air Force’s Hall of Fame in a ceremony in her honor at the Pentagon; the Air Force hailed her as one of “the leaders of the early years of the Air Force space program.” West says that she hopes her example will inspire another generation of female pioneers. “I think I did help,” she reflects. “The world is opening up a little bit and making it easier for women. But they still gotta fight.”