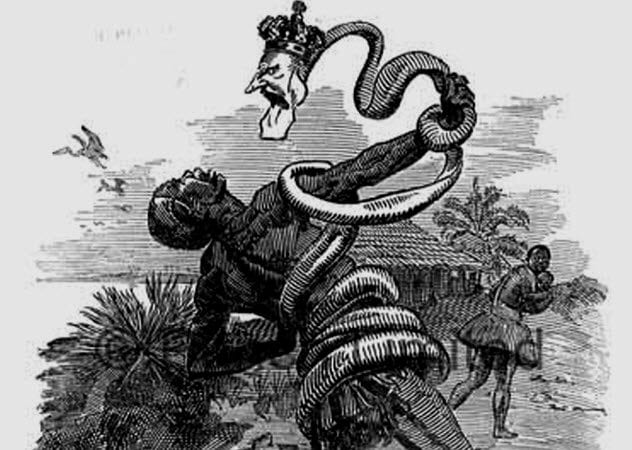

From 1885 to 1908, Belgian King Leopold II took control of the Congo. He turned the nation into a moneymaking machine by farming ivory and rubber and building a fortune on the labor of the people who lived there. Things quickly got out of control. Leopold’s harsh policies to keep people working turned into a brutal reign of mutilations and terror that led to the deaths of an estimated 10 million people in a few short years. Life in the Congo Free State was a waking nightmare, the likes of which the world had never seen. Hopefully, we will never see it again.

Thirty-Two Towns Were Destroyed While Mapping The Congo

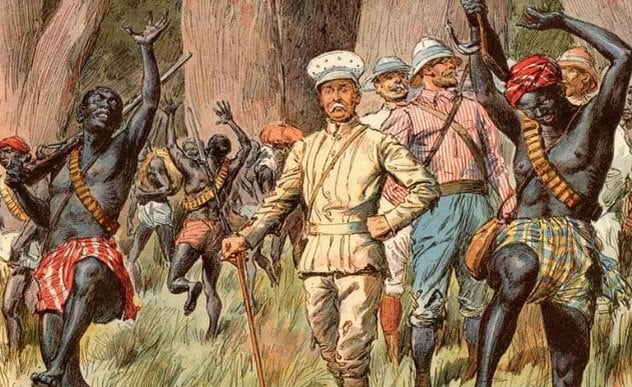

King Leopold II hired a British explorer, Henry Morton Stanley, to help him establish the Congo Free State. Stanley had already explored and mapped most of the Congo River and had experience with the people who lived there. Stanley wasn’t evil; he entered the country with no intention other than to explore. His men and the natives of the Congo, though, had vastly different cultures. They didn’t understand each other. Those misunderstandings turned into terrible fears and soon boiled into brutal violence.

At one point in the expedition, seven tribes convened and confronted Stanley. They had seen him writing in his journal. This, they were sure, was a form of witchcraft. He would have to burn his notebook, they demanded, or he and his men would be killed.

Stanley struck back. He started shooting at the Congolese when he saw them. By the end of the expedition, he had burned down 32 of their towns. His men, though, were even worse. Men in the rear column went wild and started kidnapping and raping African women or flogging the men to death for the smallest infractions.

This was the start of the Congo Free State. Leopold II hired these men to turn the area into a workhouse, and they did it by enslaving the people. Their cruelty set the tone for the future of the state and the darkness that would soon envelop the Congo.

The Entire Population Was Enslaved

When King Leopold got the legal right to take control of the Congo, he started bleeding it dry for profits. Stanley had reported temples of ivory, and people had found caches of rubber there. So Leopold was determined to make it profitable. He turned two-thirds of the country into his own private land. The people there were forced to work for him.

At first, these people were given a penny per pound of rubber, but Leopold soon stopped even giving them pennies. Instead, he called harvesting rubber a tax that every person who lived on the land was required to pay. These people had no idea that their land had been sold, and now they were being forced into labor to live on it.

Their quotas were huge. The average person had to work 20 days per month just to meet his rubber quota, and they weren’t paid for it. They would have to meet their quotas first. Then, when they had spare time left over, they could work to feed their families.

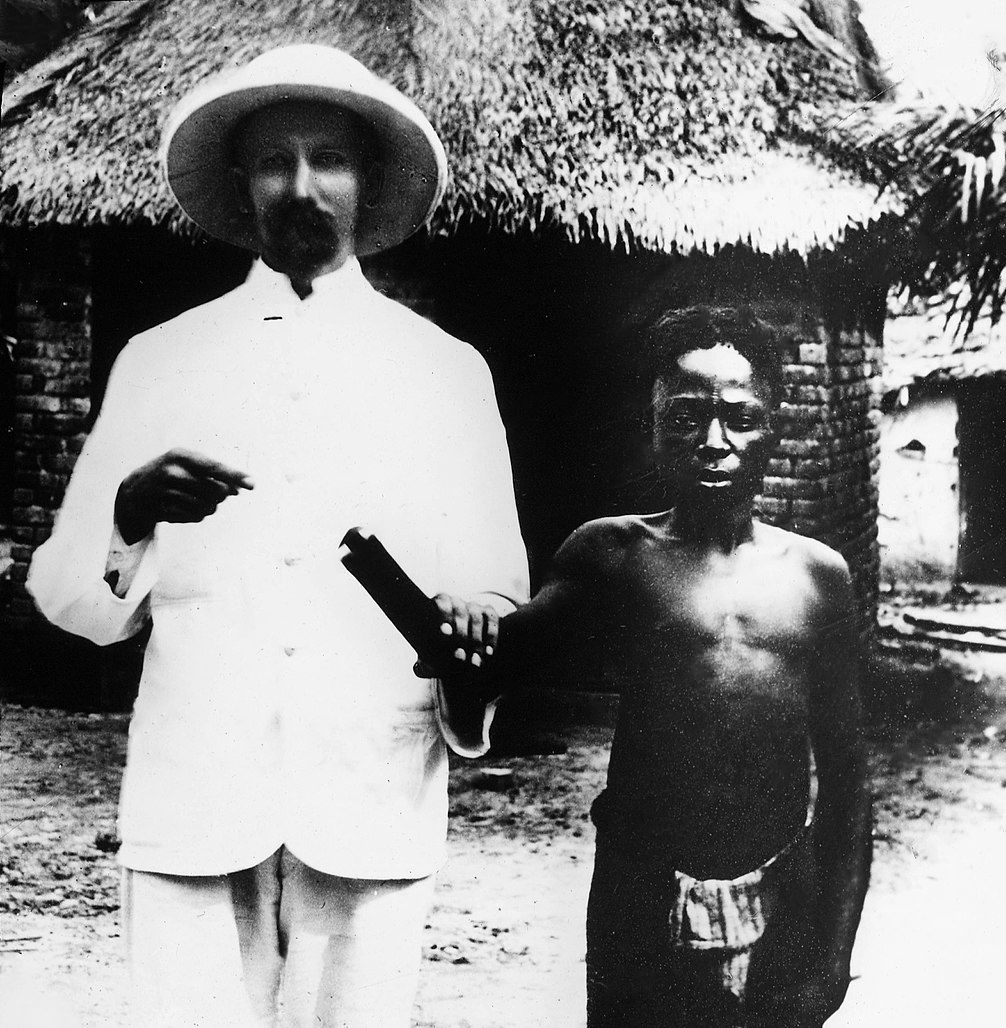

Workers Who Didn’t Meet Their Quotas Were Dismembered And Killed

Rubber profits boomed. By the 1890s, King Leopold was selling more rubber than he could harvest. For the people in the Congo, this meant that their quotas went up, and meeting the rubber tax became nearly impossible. And that was a problem—because failure to meet your quota could be punishable by death.

African soldiers were enlisted to enforce these rules, but that left a risk for the Belgians. These soldiers might spare their victims or waste their ammunition on something else. So the Belgians set up a law: Every time a worker was killed, the African soldiers had to chop off and deliver his hand.

The soldiers followed their orders because they were afraid of what would happen to them if they didn’t. They were required to meet their quotas by filling baskets with hands, sometimes even gathered from their own mothers.

After killing an old man in front of a missionary, an African soldier explained why he did it. “Don’t take this to heart so much,” the soldier told the missionary. “They kill us if we don’t bring the rubber. The commissioner has promised us if we have plenty of hands he will shorten our service. I have brought in plenty of hands already, and I expect my time of service will soon be finished.”

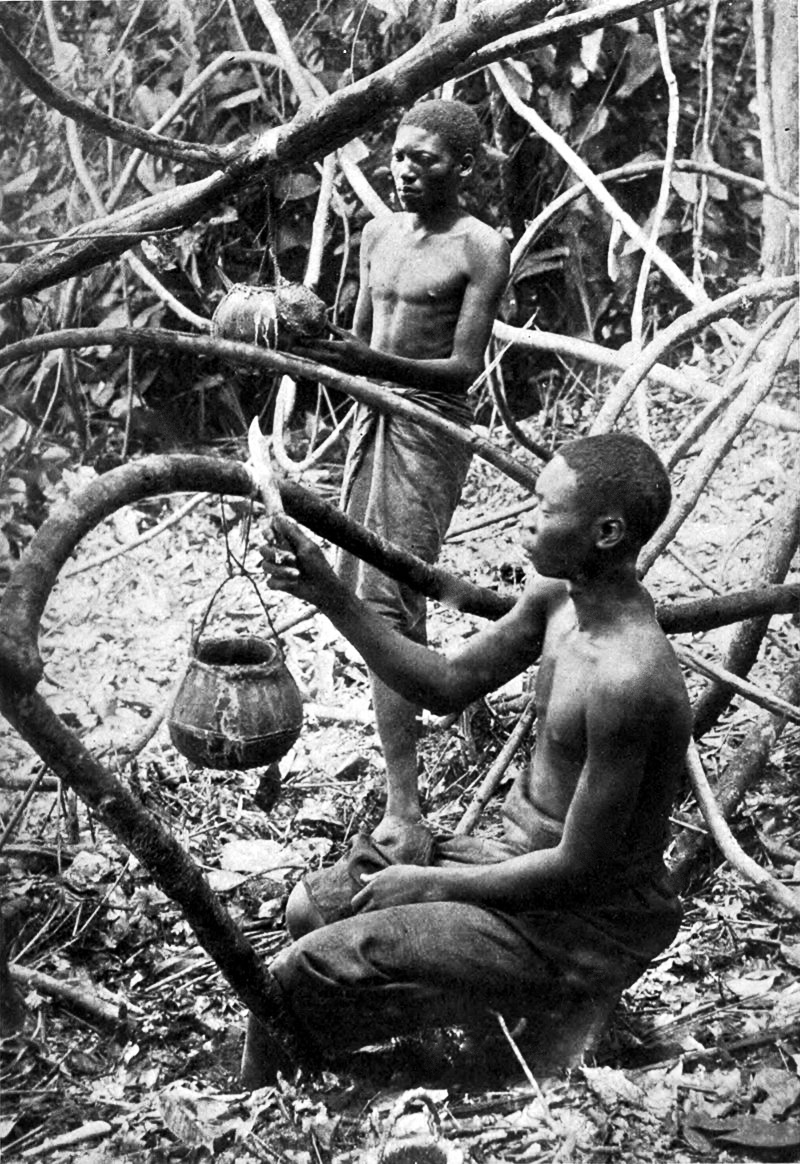

Gathering Rubber Was Deadly

Even with the workers’ looming fear of death, gathering this rubber was difficult. It had to be gathered from vines, which were hard to find and often hung high up in the trees. The easier ones were gathered quickly, and the workers were soon forced to climb higher and higher to get anything. This was dangerous. Many would slip and fall to their deaths.

Often, the people couldn’t meet their quotas and that left them terrified. There was a very real risk that they might be killed and mutilated for their failures. Some would chop up the vines to squeeze out a little extra sap. It worked, but it eliminated those vines as a resource. So, if the workers were caught doing it, they risked beatings or death. After catching a worker chopping a vine, one commissioner wrote a note about it. “We must fight them until their absolute submission has been obtained,” he wrote, “or their complete extermination.”

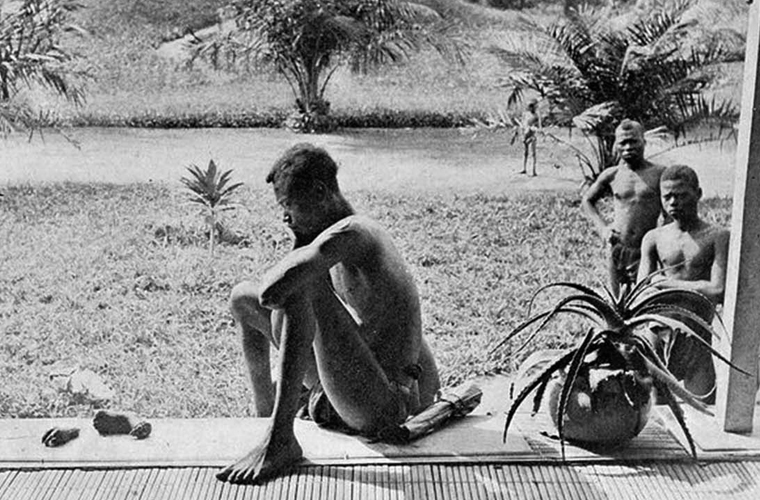

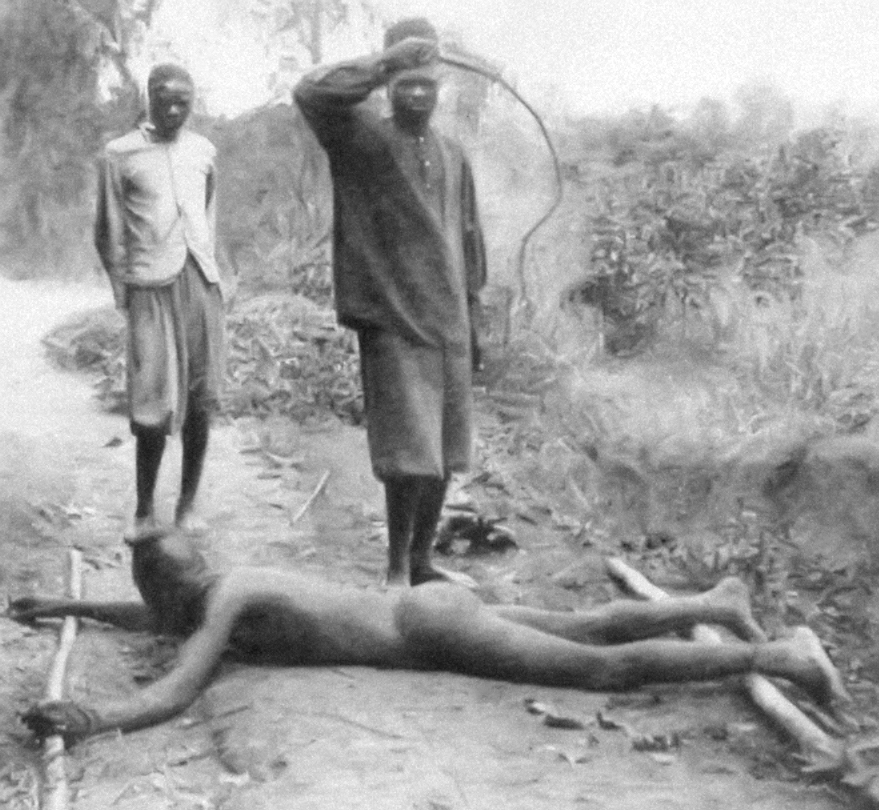

Workers Were Brutally Beaten

Not every worker who missed his quota was killed right away. Different commissioners handled it in different ways. Some were satisfied with removing the workers’ hands, but other commissioners gave the workers savage beatings.

The villagers were given number discs around their necks so that their overseers could keep track of their quotas. If the workers fell short by a small amount, they would get 25 lashes with a whip. In harsher cases, they might get 100. These beatings were done with a strong whip made of hippopotamus hide that could break the skin quickly. Sometimes, the victims died.

When other Europeans started traveling to the Congo and saw what was happening, they were shocked. The people there, though, were unimpressed. One European officer reported that he had complained to Mr. Goffin, the secretary of the Railway Company in the Congo, that he had seen men kicked, whipped, and chained by their necks.

To Mr. Goffin, though, this was just business as usual. “Mr. Goffin shrugged his shoulders,” the officer wrote, “and said that was nothing.”