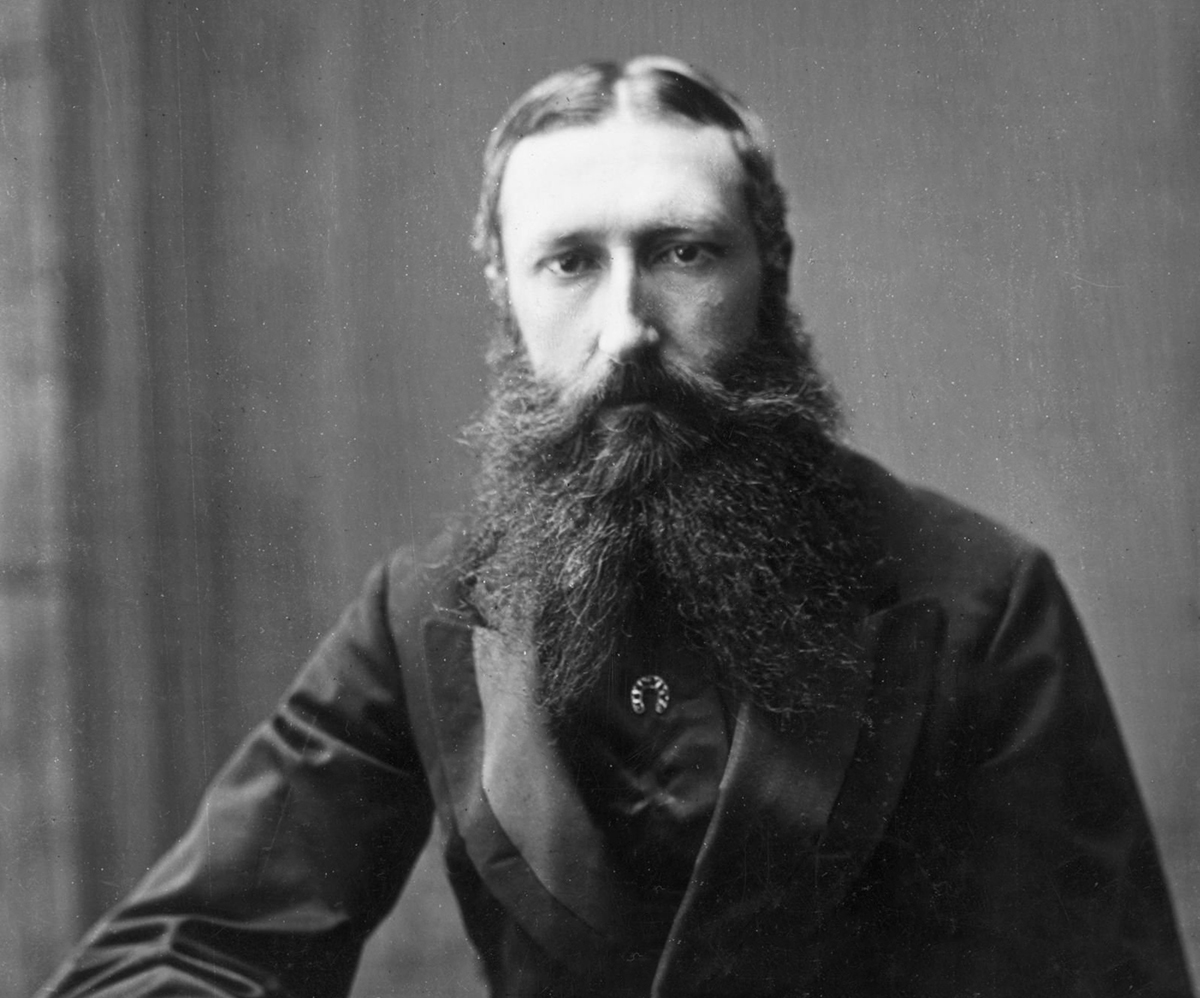

Leopold II, French in full Léopold-Louis-Philippe-Marie-Victor, Dutch in full Leopold Lodewijk Filips Maria Victor, (born April 9, 1835, Brussels, Belgium—died December 17, 1909, Laeken), king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909. Keen on establishing Belgium as an imperial power, he led the first European efforts to develop the Congo River basin, making possible the formation in 1885 of the Congo Free State, annexed in 1908 as the Belgian Congo and now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Although he played a significant role in the development of the modern Belgian state, he was also responsible for widespread atrocities committed under his rule against his colonial subjects.

The country of Belgium itself was only about five years old at the birth of Leopold II, who became the eldest surviving son of Leopold I, the first king of the Belgians, and his second wife, Louise-Marie of Orléans. Then, as they would be into the 21st century, most of the royal families of Europe were related. For instance, Leopold II was the first cousin of Queen Victoria of Britain. He became Duke of Brabant in 1846 and served in the Belgian army. In 1853 he married Marie-Henriette, daughter of the Austrian Archduke Joseph, Palatine of Hungary, and became king of the Belgians on his father’s death in December 1865.

Most of the monarchs in western Europe had been forced to largely yield political power to the electorate by the late 19th century, so Belgium’s parliament and cabinet were the real focus of power, but Leopold used the prestige of the monarchy to lobby for pet projects. Although the domestic affairs of his reign were dominated by a growing conflict between the Liberal and Catholic parties over suffrage and education issues, Leopold concentrated on developing the country’s defenses. Aware that Belgian neutrality, maintained during the Franco-German War (1870–71), was imperiled by the increasing strength of France and Germany, he persuaded parliament in 1887 to finance the fortification of Liège and Namur.

The royal coffers would become a central focus of Leopold’s life, and he once grumbled to German Emperor William II while watching a parade in Berlin, “There is really nothing left for us kings except money!” Leopold soon decided that the best way to acquire wealth would be by establishing an African colony, at a time when the great European “Scramble for Africa” was underway. In 1870 more than 80 percent of Africa south of the Sahara was under the rule of indigenous chiefs or kings. Forty years later virtually all of it had been transformed into European colonies, protectorates, or territories ruled by white settlers.

Presenting himself as a philanthropist eager to bring the benefits of Christianity, Western civilization, and commerce to African natives—a guise that he perpetuated for many years—Leopold hosted an international conference of explorers and geographers at the royal palace in Brussels in 1876. Several years later he hired the explorer Henry Morton Stanley to be his man in Africa. For five years Stanley traveled up and down the immense waterways of the Congo River basin, setting up trading posts, building roads, and persuading local chiefs—almost all of them illiterate—to sign treaties with Leopold. The treaties, some of which appear to have been subsequently doctored to Leopold’s liking, were then put to use by the Belgian monarch.

Although Belgium’s government felt that colonies would be an extravagance for a small country with no navy or merchant marine, that situation suited Leopold perfectly. He persuaded first the United States and then all the major nations of western Europe to recognize a huge swath of Central Africa—roughly the same territory as the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo—as his personal property. He called it État Indépendant du Congo, the Congo Free State. It was the world’s only private colony, and Leopold referred to himself as its “proprietor.”

The king then embarked on an ultimately successful effort to make a vast fortune from his new possession. Initially, he was most interested in ivory, a material that was greatly valued in the days before plastics because it could be carved into a great variety of shapes—statuettes, jewelry, piano keys, false teeth, and more. For some years ivory was a principal source of the great wealth that Leopold and his associates drew from the new colony. In his novella Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad, who spent six months in the Congo in 1890 as a steamboat officer, gives a searing picture of the brutal and voracious European quest for Congo ivory.

By the early 1890s, a new source of riches had appeared. A worldwide rubber boom was underway, kicked off by the invention of the inflatable bicycle tire and spurred on by the rise of the automobile and the use of rubber in industrial belts and gaskets, as well as in coating for the telephone and the telegraph wires. Throughout the tropics, people rushed to sow rubber trees, but those plants could take many years to reach maturity, and in the meantime, there was money to be made wherever rubber grew wild. One lucrative source of wild rubber was the Landolphia vines in the great Central African rainforest, and no one owned more of that area than Leopold. Detachments of his 19,000-man private army, the Force Publique, would march into a village and hold the women hostage, forcing the men to scatter into the rainforest and gather a monthly quota of wild rubber. As the price of rubber soared, the quotas increased, and as vines near a village were drained dry, men desperate to free their wives and daughters would have to walk days or weeks to find new vines to tap.

Other parts of the Congo economy, from road building to chopping wood for steamboat boilers, are operated by forced labor as well. The effects were devastating. Many of the women hostages starved, and many of the male rubber gatherers were worked to death. Tens, possibly hundreds, of thousands of Congolese fled their villages to avoid being impressed as forced laborers, and they sought refuge deep in the forest, where there were little food and shelter. Tens of thousands of others were shot down in failed rebellions against the regime. One particularly notorious practice grew out of the suppression of those rebellions. To prove that he had not wasted bullets—or, worse yet, saved them for use in a mutiny—for each bullet expended, a Congolese soldier of the Force Publique had to present to his white officer the severed hand of a rebel killed. Baskets of severed hands thus resulted from expeditions against rebels. If a soldier fired at someone and missed, or used a bullet to shoot a game, he then sometimes cut off the hand of a living victim to be able to show it to his office.

With women as hostages and men forced to tap rubber, few able-bodied adults were left to hunt, fish, and cultivate crops. Millions of Congolese then found themselves suffering near-famine, which made them vulnerable to diseases they otherwise might have survived. Furthermore, as in any society where men and women are separated, traumatized, or in flight as refugees, the birth rate dropped precipitously. No one will ever know the precise figures, but, from all these causes, demographers estimate that between 1880 and 1920 the population of the Congo may have been slashed by up to 50 percent, from perhaps 20 million people at the beginning of that period to an estimated 10 million at the end.

The forced-labor system for gathering rubber was swiftly copied by French, German, and Portuguese colonial officials with equally fatal results. Because the system’s effects in the Congo could so easily be blamed on one man, who could safely be attacked because he did not represent great power, an international outcry focused on Leopold. That pressure finally forced him to relinquish his ownership of the territory, and it became the Belgian Congo in 1908. Leopold, however, made the Belgian government pay him for his prized possession. He died the following year. Because his only son had predeceased him, Leopold’s nephew Albert I succeeded to the throne.

By the end of his life, Leopold was unpopular with his people, but, ironically, that had much less to do with his actions in Africa than with the conduct of his personal life. He spoke contemptuously of Belgium’s small size, could not speak proper Dutch, the native language of more than half of its citizens, spent long winters in luxurious quarters on the French Riviera, and was estranged from two of his three daughters. Moreover, he had a well-known penchant for teenage girls, and, when he was age 65, he began a liaison with a teenage former prostitute who bore him two additional children.

He is remembered in Belgium for some of what he built with his Congo wealth, such as the monumental Arcade du Cinquantenaire in Brussels, and for his advocacy of strong fortifications in the eastern part of the country, which slowed the advance of German troops in 1914 at the beginning of World War I. His most important legacy, however, remains the human catastrophe that the rubber-forced labor system brought to the Congo—a heritage that continued to echo in that region more than a century after Leopold’s death.