Henry Ossian Flipper was born on March 21, 1856, near Thomasville, Georgia, into a family marked by resilience and ambition despite the oppressive circumstances of slavery. His parents, Festus, a skilled shoemaker, and Isabella Flipper, instilled a drive for excellence in their children. This foundation propelled Henry and his younger brothers to achieve prominence in their respective fields: Henry as a military officer, Joseph as an AME bishop, E.H. as a physician, Carl as a college professor, and Festus Jr. as a farmer. Their collective success reflected the family’s commitment to education and determination to rise above their origins.

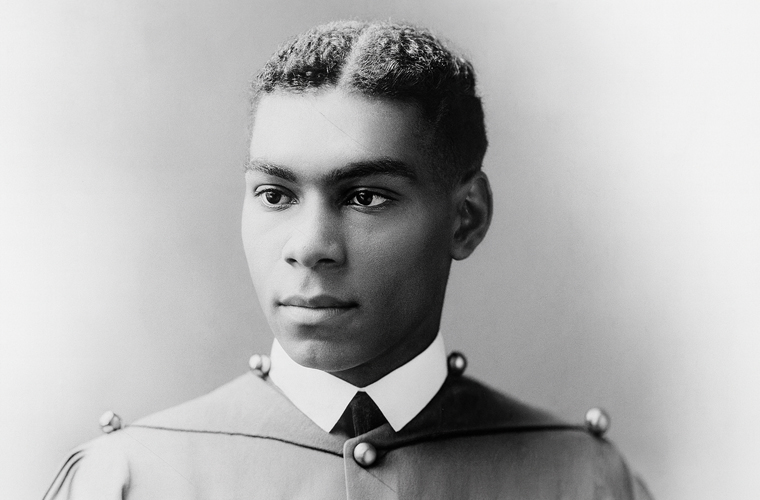

In 1877, Flipper achieved a historic milestone as the first African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point. Commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army, he was assigned to the 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiment, one of the all-Black units known as the Buffalo Soldiers, stationed at various posts in the American West. His assignments took him to Fort Sill in Oklahoma and several Texas forts, including Fort Elliott, Fort Concho, Fort Davis, and Fort Quitman. Flipper distinguished himself during the Victorio Campaign of 1879–1880, a grueling conflict against Apache leader Victorio in Texas and New Mexico. Serving with A Troop under Captain Nicholas M. Nolan, he became the first Black officer to lead Buffalo Soldiers in combat, a testament to his leadership and courage.

Trained as an engineer, Flipper left a lasting mark at Fort Sill by designing a drainage system, now known as Flipper’s Ditch and recognized as a national monument. This innovative system effectively reduced standing water, significantly curbing malaria outbreaks at the fort. His engineering skills showcased his ability to combine technical expertise with practical solutions, earning him respect among his peers.

However, Flipper’s military career was abruptly derailed in 1881 while he served as quartermaster at Fort Davis, Texas. Accused of embezzling $2,000 in government funds and lying about it when confronted, he faced a U.S. Army court-martial on September 17, 1881. Although acquitted of the embezzlement charge, he was found guilty of “conduct unbecoming of an officer and a gentleman,” a verdict many believed was influenced by racial prejudice. Supporters argued that the true motive behind the charges was Flipper’s close relationship with Mollie Dwyer, the sister-in-law of Captain Nolan, which stirred resentment among some white officers. The harsh penalty—a dishonorable discharge—was particularly striking when compared to two white officers who, despite being found guilty of embezzlement, faced no such dismissal. Despite appeals from Flipper’s advocates, President Chester A. Arthur upheld the court-martial’s decision, and Flipper was discharged from the Army on June 30, 1882. For the rest of his life, Flipper tirelessly sought to clear his name, challenging the charges and the systemic racism he believed underpinned them.

Following his dismissal, Flipper settled primarily in El Paso, Texas, until 1919, where he built a multifaceted career as a civil mining engineer, surveyor, translator, newspaper editor, historian, and folklorist, working across Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico. His fluency in Spanish was a key asset, enabling him to navigate and succeed in diverse professional and cultural environments. In 1921, he moved to Washington, D.C., to serve as an assistant to former U.S. Senator Albert Fall of New Mexico, who had been appointed Secretary of the Interior by President Warren G. Harding. By 1923, Flipper transitioned to the petroleum industry, employed by Texas oilman William F. Buckley Sr. as an engineer in Venezuela, where he applied his technical expertise to a new field.

Flipper documented his experiences in two autobiographies: The Colored Cadet at West Point, published in 1878, which detailed his groundbreaking journey through the military academy, and Negro-Frontiersman, The Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper, completed in 1916 but published in 1963 after being edited by Theodore D. Harris. These works provide a vivid account of his challenges and achievements, offering insight into the life of a trailblazing Black man in a racially divided era.

Despite his many accomplishments, Flipper’s legacy is often overshadowed by the racially charged court-martial that ended his military career. After retiring to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1931, he lived quietly until his death on May 3, 1940, at the age of 84. Decades later, his fight for justice was vindicated. In 1976, President Jimmy Carter posthumously granted Flipper an honorable discharge, acknowledging the injustice of his dismissal. In 1999, President Bill Clinton issued a full presidential pardon, further affirming Flipper’s innocence and cementing his place in history as a pioneer who overcame immense barriers. His story remains a powerful testament to resilience, ingenuity, and the enduring struggle for equality.