In 1931, the last surviving captive of an American slave ship was interviewed by Zora Neale Hurston. It was not the only time Hurston would preserve a vital, endangered piece of American culture.

Hurston interviewed Cudjo Lewis multiple times from his home in Plateau, Alabama, where he recounted his abduction from Benin at age 19. Lewis was transported aboard the Clotilda, the last known ship to bring slaves to the U.S.

Her manuscript of Lewis’ life, called “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo,’” was recently brought out of obscurity from the archives at Howard University and will be published on May 8, decades after her attempts to find a publisher failed.

Zora Hurston beating the hountar, or mama drum, 1937.

Zora Hurston beating the hountar, or mama drum, 1937.

While Hurston’s literary portrait of Lewis’ life provided an intimate account of the legacy of slavery, it met with criticism from many black academics and thinkers of the time, who felt the manuscript was counterproductive to the mission of uplifting the perception of African Americans among the dominant white society.

Hurston insisted on writing Lewis’ story the way he spoke it: in a thick, vernacular dialect that left many of her black contemporaries worried the book would reinforce stereotypes.

An author, anthropologist, and Harlem Renaissance legend, Hurston was also a folklorist, dedicated to strict, accurate field transcriptions and the idea that black culture was not monolithic, according to Anna Lillios, a professor of English at the University of Central Florida.

Lillios said Hurston’s mentor — “father of anthropology” Franz Boaz — urged her “to collect the folklore [and] remnants” of an African-American culture he felt was disappearing.

So Hurston proposed anthropological research on Florida folklife to the Federal Writers Project, a 1935 program implemented through the United States Work Progress Administration (WPA) as a means to employ researchers and historians.

Stephen Winick, editor, and folklorist at the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center, where a collection of recordings from Hurston’s Florida Folklife project can be found, said Hurston was paid by the WPA and Florida government to collect folklore local to areas of the state where she grew up.

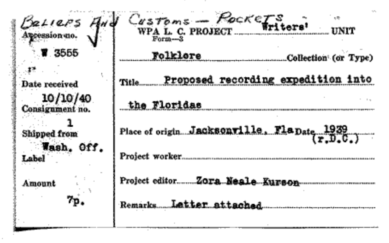

Hurston’s Florida folklife research proposal. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Hurston’s Florida folklife research proposal. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

“Part of what they were doing was creating a set of travel guides for all the states,” Winick said. “But it was also just a way of documenting American culture.”

Unlike other anthropologists from the project, Hurston didn’t use recording equipment in the field. She took data by hand, learned songs and verses by heart, and recorded them herself.

In one recording, “Halimuhfack,” she describes her process, saying she would “just get in the crowd with people” and listen as best she could. Then, she said, she would “sing [verses] back to the people” until they approved of her rendition.

In “Let the Deal Go Down,” Hurston paints a vivid gambling scene she witnessed during a field excursion in 1939:

Let the deal go down boys,

Let the deal go down.

[spoken]

There you go Blue Front,

I’ll show you about getting a card and telling a lie about it.

Put up some more money!

Her exuberant recitation of the rhyme was characteristic of her penchant for performance. While she didn’t write any of the poetry she recorded, she made it her own in the retelling.

But Hurston’s work was under constant social and economic pressure. In addition to an ongoing struggle with money, Winick said, Hurston and her black colleagues conducted research in the middle of racially turbulent times, because Florida was still a segregated state.

“The challenge for them was that they couldn’t even go to the state offices where they were employed,” Winick said. “Except for certain times when they were expected and when Zora had been invited.”

Hurston’s work lives on not only due to her literary fame but for her unflinching dedication to African-American folklife.

Lillios said Hurston’s portrait of Lewis is a prime example of her vivid, meticulous storytelling.

“She’s giving anthropological data and looking at Cudjoe Lewis from an anthropological viewpoint, but the story is so riveting, the story of his life, and the way she tells it,” she said.

“I think that is timeless.”