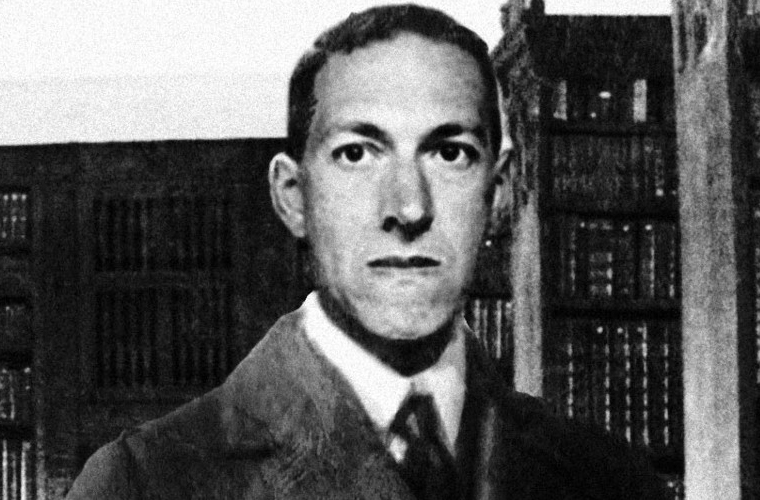

Howard Phillips Lovecraft, the mastermind of cosmic horror, brought madness and existential dread to new heights. He ruptured the imagination in tandem with history itself becoming unimaginable in the early 20th century. His mythologies seep into the works of Ridley Scott, Stephen King, Guillermo del Toro, Joss Whedon, and countless others, and his stories are rigorously dissected in academic schools ranging from speculative realism and object-oriented philosophy to posthumanism and human-animal studies. Video games are indebted to his cosmic universe and the grotesque monsters that within it abound. And cruder, yet ingenious, Lovecraftian appearances have been resurrected in popular culture, ranging from South Park and heavy metal to pornography and sex toys. But he is also a man whose virulent racism and bigotry induced in him a “poetic trance,” as Michel Houellebecq once phrased it.

So long as modern stories of white genocide, superpredators, and the alleged master race find fertile ground on American soil, the contemporary relevance of Lovecraft will extend beyond what some fans care to admit. His bigotry and race-inflected narratives can’t be wished away, cherry-picked, or swept under the rug in favor of his more widely known literary techniques and accomplishments—especially as hell-bent right-wing insurgents proudly claim him as a true elaborator of reactionary horrors. His stories and politics are still breathing, even the most defiled and rotten among them.

Making no efforts to conceal his bigoted theories, Lovecraft took to pen and publication with the most grotesque appraisals of those he deemed inferior. His letters overflow with anti-Semitic conspiracy theories of an underground Jewry pitting the economic, social, and literary worlds of New York City against “the Aryan race.” He warned of “the Jew [who] must be muzzled” because “[he] insidiously degrades [and] Orientalizes [the] robust Aryan civilization.” His sympathies with rising fascism were equally transparent. “[Hitler’s] vision . . . is romantic and immature,” he stated after Hitler became chancellor of Germany. “I know he’s a clown but god I like the boy!”

And his contempt for blacks ran even deeper. In his 1912 poem entitled “On the Creation of Niggers,” the gods, having just designed Man and Beast, create blacks in semi-human form to populate the space in between. Regarding the domestic terrorism of white minorities in the predominantly black Alabama and Mississippi, he excused them for “resorting to extra-legal measures such as lynching and intimidation [because] the legal machinery does not sufficiently protect them.” He lamented these sullen tensions as unfortunate, but nevertheless says that “anything is better than the mongrelisation which would mean the hopeless deterioration of a great nation.” Miscegenation permeates his letters and stories as his most corporeal fear; he insists that only “pain and disaster [could] come from the mingling of black and white.”

His prejudice, like that of many figures who’ve achieved the status of cultural icon, is often treated with apologia, disregard, or as a personal flaw within an otherwise great man. Never was this clearer than in the debate in 2010 surrounding the World Fantasy Award, a prestigious literary prize for fantastical fiction molded in the caricatured bust of Lovecraft himself, which a number of writers came to petition. Established in 1975 in Lovecraft’s home city of Providence, Rhode Island, the “Howard” award was intended to “give a visible, potentially usable, sign of appreciation to writers working in the area of fantastic literature, an area too often distinguished by low financial remuneration and indifference.” Like most awards named after an artist, it was intended to acknowledge Lovecraft’s precedent in the field of fantastical fiction.

But as his racism and xenophobia became more widely known and discussed, it became obvious how flippant and egregious it was to potentially award black nominees with the face of a man who once proclaimed that “the Negro is fundamentally the biological inferior of all White and even Mongolian races.” As Nnedi Okorafor, the first black person to ever win a WFA for Best Novel, put her internal conflict, “A statuette of this racist man’s head is in my home. A statuette of this racist man’s head is one of my greatest honors as a writer.” The award was remodeled in 2016, but not without the kicking and screaming of Lovecraft’s pious defenders. Prominent Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi, who has made insightful contributions to the study of weird fiction, refuted the arguments for changing the award stating that 1) the award “acknowledges Lovecraft’s literary greatness . . . [which] says nothing about the person or character” and 2) “it suggests that Lovecraft’s racism is so heinous a character flaw that it negates the entirety of his literary achievement.”

The first comment is particularly strange, considering the award is the mold of an actual person rather than a literary reference. If the goal is to highlight the genius of the author, why not make the statuette reflective of his universe rather than of the literal face of the man himself? After all, Lovecraft was the creator of an influential cosmos replete with landscapes of unfathomable monsters and profound alien architectures. There is no drought in the search for Lovecraftian imagery to pay homage to his legacy and precedent in the field of weird fiction.

But Joshi’s second point is more telling, as it pits Lovecraft’s racism against his literature. He tries to save the latter by separating it from the former. But the need to “save” a man dubbed the “horror story’s dark and baroque prince” by Stephen King is itself questionable. His legacy is firmly planted. His cosmology sprawls from popular culture to niche corners of scholasticism. Complaints of a potentially tarnished reputation are more concerned with bolstering the illusion of Lovecraft as a sacrosanct figure. Even further, to divorce his racism from his literary creations would be a pyrrhic victory; what results is a whitewashed portrait of a profound writer. And from a critical standpoint, what’s lost is any meaningful grappling with the connection between Lovecraft’s racism and the cosmic anti-humanism that defined his horror.

“To divorce his racism from his literary creations would be a pyrrhic victory; what results is a whitewashed portrait of a profound writer.”

In 1927, Lovecraft’s oft-quoted take on cosmic horror appeared in Weird Tales: “Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.” One must “forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, [have] any existence at all.” Crucial to all of his stories is the question of the outside, which breaks in from unknown dimensions and upsets his character’s perception of space, time, and history.

Traditionally, horror stories concern a monstrous perversion of the status quo, with characters seeking its resolution or restoration by extraordinary, and sometimes desperate, means. Even if all goes to hell, the protagonist’s attempts were nonetheless depicted as both noble and practical. But Lovecraft’s stories went further, accomplishing what Mark Fisher, in The Weird and the Eerie (Repeater), calls “catastrophic integration,” where the outside breaks into “an interior that is retrospectively revealed to be a delusive envelope, a sham.” That is: the main character will encounter unknown entities, dreamscapes, dimensions, and underworlds that shatter all previously held notions of science, history, and humanity. Characters would discover cities with “no architecture known to man or to human imagination” which contain “monstrous perversions of geometrical laws attaining the most grotesque extremes of sinister bizarrerie.” Lovecraft’s monsters were even more perplexing than his cities, displaying physiologies that defied all known biological principles, “outreaching in grotesqueness the most chaotic dreams of man.” Rather than a return to the status quo, in Lovecraft’s conclusions, the universe is revealed to be impossibly bleak and beyond possible human understanding. There is no hero in these tales. There are but two options his characters are thus faced with: go mad or run.

Knowing the primacy of existential dread within Lovecraft’s stories, is it then possible to separate his racism from his creative output? In the end, is Lovecraft’s nihilism ultimately colorblind, “All Lives Don’t Matter in the Vast Cosmos-at-Large”? Not quite. As Jed Mayer argues in The Age of Lovecraft, the “mingling of horror and recognition that accompanies the encounter with the nonhuman other is one that is vitally shaped by Lovecraft’s racism.” The admixture of his maniacal bigotry and hysterical racism ignite stories of nihilism often based on the master-race ideology. In the same anthology, China Miéville writes that “the anti-humanism one finds so bracing in him is an anti-humanism predicated on murderous race hatred.” This provides all the more reason to place Lovecraft’s racism at the forefront of examinations of his oeuvre.

One of Lovecraft’s notable tales concerns a troubled detective who comes across a “hordes of prowlers” with “sin-spitted faces . . . [who] mix their venom and perpetrate obscene terrors.” They are of “some fiendish, cryptical, and ancient pattern” beyond human understanding, but still, retain a “singular suspicion of order [that] lurks beneath their squalid disorder.” With “babels of sound and filth,” they scream into the night air to answer the nearby “lapping oily waves at its grimy piers.” They live within a “maze of hybrid squalor near an ancient waterfront,” space “leporous and cancerous with evil dragged from elder worlds.” One could be forgiven for mistaking this space as an evil abyss populated by beasts from the mythical Necromonicon. However, this vignette is from his short story, “The Horror at Red Hook.” And the accursed space is not some maleficent mountain of the The Great Old Ones, but the Brooklyn neighborhood right off the pier. The brutish monsters, conduits for a deeper evil, are the “Syrians, Spanish, Italian and Negro[s]” of New York City.

In all of his collected works, this may be the one where his racist opinions are made the most explicit. A relatively straightforward detective story, “The Horror of Red Hook” unfolds in Lovecraft’s typical fashion; the deeper evil is slowly brought to light in scenes of intermixing immigrants whose neighborhood is revealed in the final act to be the literal gateway to hell. Strong anti-immigration sentiments and gaudy displays of sympathy for racist policing appear throughout, with references to immigrants that range from “monsters” to “contagions.” We see blacks and immigrants, the bringers of chaos in American law and order, subjected to scientific scrutiny that perceives them as a danger to the master race.

The story was instigated by Lovecraft’s tenure in Brooklyn from 1924 to 1926, a time of shifting demographics, greatly affected by the Great Migration of blacks from the South to the Midwest and the North. In one letter, Lovecraft describes living in Brooklyn as being “imprisoned in a nightmare.” And upon leaving, he swore that “not even the threat of damnation could induce me to dwell in the accursed place again.” His wife Sonia recounted that “whenever he would meet crowds of people—in the subway, or at the noon hours, at the sidewalks of Broadway or crowds, whoever he happened to find them, and these were usually the workers of the minority races—he would become livid with anger and rage.”

It should come as no surprise that a racist imagination possesses an uncanny ability to concoct the most outlandish and fiendish representations of minorities and immigrants; preexisting social hierarchies and political forces give those depictions life and validity. Darren Wilson’s horror-ridden tale of the death of Mike Brown, delivered to a grand jury on September 16, 2014, shows one strain of the continuous thread of black youth enlivened in the racist imaginary as a monstrosity to be met with force. It’s the tale a child, if the child he may be called, whose presence and demeanor were so dangerous that the only solution was a bullet to the brain. “I’ve never seen anybody look that, for lack of a better word, crazy,” Wilson testified. “That’s the only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.” In Wilson’s story, even the spraying of firepower can’t stop Brown, who begins to feed on the violence. Wilson claims that “at this point, it looked like he was almost bulking up to run through the shot.” Therefore, in a desperate move, the grand jury is told, the fatal silver bullet was fired and “when it went into him, the demeanor on his face went blank, the aggression was gone, it was gone, I mean I knew he stopped, the threat was stopped.”

“This isn’t to suggest that Darren Wilson is a specifically Lovecraftian storyteller, but to show how the weight of fantastic imagery can and has been violently deployed against people of color.”

Yet another racist campfire tale from an unreliable narrator. It’s so cliché it should be criminal. Yet Darren Wilson is alive and Mike Brown is dead. In a just world, referring to an 18-year-old as a bullet-thirsty maniacal demon beyond human understanding would not only be insufficient in any court of law—it would qualify as perjury or pure insanity. But the main goal of Wilson’s monster-laden narrative wasn’t to state any verifiable facts. It was to conjure fear. For this, his story didn’t need to be true. No story of any cop killing a black man, child, woman, or trans person needs to be true. But like any convincing piece of fantastic fiction, it must at least engage with some level of world-building, pulling from an already established mythos that defines how the world works.

Lucky for Wilson, stories of the “Negro Beast”, the “Big Black Brute”, and the “Superpredator” already proliferate in the white supremacist, capitalist mythos and prove useful for reactionaries in enforcing and imagining political ends. Rekia Boyd, Tamir Rice, Shereese Francis, Trayvon Martin, and Jordan Edwards are but a few of the countless whose skin, presence, demeanor, and even mental illness provoked a fear that is entirely “plausible” within the stories we are told and re-told about race. Right-wing and liberal commentary on “black on black crime” and “the poverty of black culture” reads like a mere refinement of Lovecraft’s racist intonations about “patterns of primitive half-ape savagery” and “shocking and primordial tradition.” The essential message of black depravity and lowliness remains firmly intact in both.

This isn’t to suggest that Darren Wilson is a specifically Lovecraftian storyteller, but to show how the weight of fantastic imagery can and has been violently deployed against people of color. Lovecraft was a writer who breathed life into the reactionary anxieties and racist horrors of shifting social and global paradigms, including those of “race relations,” war, revolution, and class struggle. He was not only the “modern pope of horror” but also its grand wizard.

Lovecraft didn’t write himself out of his mythical universe, nor did he separate that universe from the real world unfolding before him. He was both an active product of his time as well as an elaborator of specific historical fears about “the decline of the West.” While he succeeded in shocking the mind out of the mundane and shattering conceptions of rationality and reason that were trying desperately to hold in the early 20th century, he couldn’t face the horrors that bled into his own psyche.