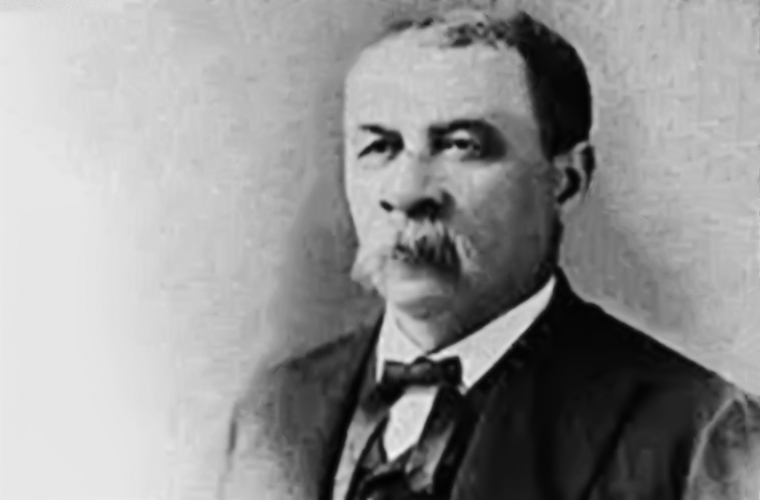

Born free in Baltimore, labor leader Isaac Myers was the son of poor workers. He attended Rev. John Fortie’s day school and at sixteen was apprenticed to James Jackson, a well-known African-American caulker in Baltimore’s shipyards. By the time the Civil War broke out, Myers had become an independent caulker.

In October 1865 white caulkers angered by black competition went on strike, demanding that black workers be excluded from waterfront work. Police joined in, and African Americans were driven from the shipyards. The unemployed black caulkers and waterfront men held a meeting. Myers suggested they form their own union, buy up a shipyard and railway line, and run their own business cooperatively. Baltimore blacks responded to Myers’s pleas for help by investing $10,000. Myers borrowed an additional $30,000 from a ship captain and set up a shipyard and railway. The cooperative called the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock opened in February 1866 and paid its three hundred workers an average of three dollars per day. Myers also organized the Colored Caulkers’ Trades Union and was named its first president. He expanded his union role to political activism, calling for civil rights and black suffrage.

The shipyard was successful almost immediately, and Myers and his partners were able to pay off their original debts within five years. The cooperative’s influence and example assured that white Baltimore workers did not exclude blacks from other fields. Soon it began hiring white workers, and Myers worked closely with the white caulkers’ union. From his collaboration, he dreamed of interracial activism on a large scale. In 1868 he was one of nine blacks invited to attend the convention of the National Labor Union (NLU), the largest white labor organization, in Philadelphia. Myers underlined the importance of interracial collaboration and asserted that blacks would be happy to work with whites for common goals.

His efforts met with white indifference, but he invited white delegates to a National Labor Convention that December in Washington, D.C. At the convention, the (black) National Labor Union was born. Myers helped write the union’s constitution and served as its president. He spent the next several months on a speaking tour, attempting unsuccessfully to draw support for the union. Myers reminded his audiences that labor could succeed only if both races united. That August he attended another NLU convention, but white and black delegates divided over blacks’ support of the Republican Party. The black NLU remained small and financially strapped. It dissolved before the end of 1871, and Myers left the labor movement.

In later life, Myers became a detective in the Post Office Department, opened an unsuccessful coal yard, and became a U.S. tax collector. He headed several black business organizations in Baltimore and was active in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, spending fifteen years as superintendent of Baltimore’s Bethel AME School and writing an unpublished sacred drama. A grand master of Maryland’s black Masons, he edited an issue of Mason’s Digest. He died in Baltimore in 1891 after a paralytic stroke.