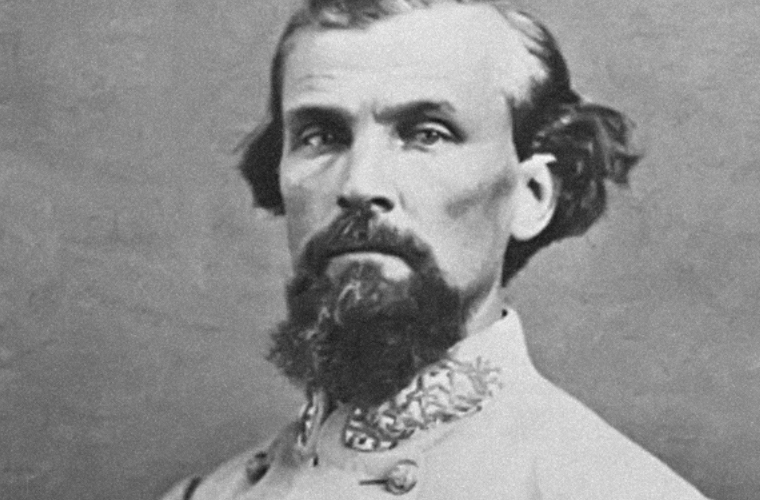

Nathan Bedford Forrest, (born July 13, 1821, near Chapel Hill, Tennessee, U.S.—died October 29, 1877, Memphis, Tennessee), was a Confederate cavalry commander in the American Civil War (1861–65) who was often described as a “born military genius.” His rule of action, “Get there first with the most men,” became one of the most often quoted statements of the war. Forrest is also one of the most controversial figures from the Civil War era. His command was responsible for the massacre of African American Union troops stationed at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, in April 1864, and he served as the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan in the early years of Reconstruction. Forrest was born into a poor family and spent his formative years in rural Tennessee and Mississippi.

His hardscrabble background contributed to the development of an aggressive and sometimes violent disposition. With the untimely death of his father, Forrest became his family’s sole provider while still a teenager. Despite his nearly nonexistent formal education, he was able to secure a measure of financial stability for his family, and, when his mother remarried, he embarked on his own ventures. In 1845 Forrest married Mary Ann Montgomery. The two would have two children, only one of whom would survive to adulthood. Forrest eventually became a millionaire, having made a fortune trading livestock, brokering real estate, planting cotton, and especially selling slaves. By the outbreak of the Civil War, he was one of the richest men in Tennessee, if not all of the South.

Shortly after the start of the war, Forrest enlisted as a private in the Confederate army, but soon thereafter, at the behest of Tennessee’s governor, he raised and supplied a cavalry unit, earning a commission as a lieutenant colonel. In the war’s early months he earned a reputation as a doggedly if sometimes brutally, determined commander who exercised a natural acumen for battlefield tactics. Forrest took part in the defense of Fort Donelson, Tennessee (February 1862), from which he and the majority of his command escaped, refusing to capitulate with the rest of the Confederate forces when the fort‘s massive garrison surrendered. Having been promoted to colonel, Forrest fought with distinction at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862), during the retreat from which he received the first of his multiple wartime wounds.

After leading a new command to a dramatic victory over Union forces at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in July, Forrest was promoted to brigadier general. After his promotion, Forrest began acting as a semi-independent cavalry commander. His command conducted raids against Union supply and communication lines, depots, and garrisons in many states in the war’s Western theatre. Forrest’s campaigns were especially detrimental to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. Some contemporaries and historians have argued that Forrest forestalled Vicksburg’s fall by several months.

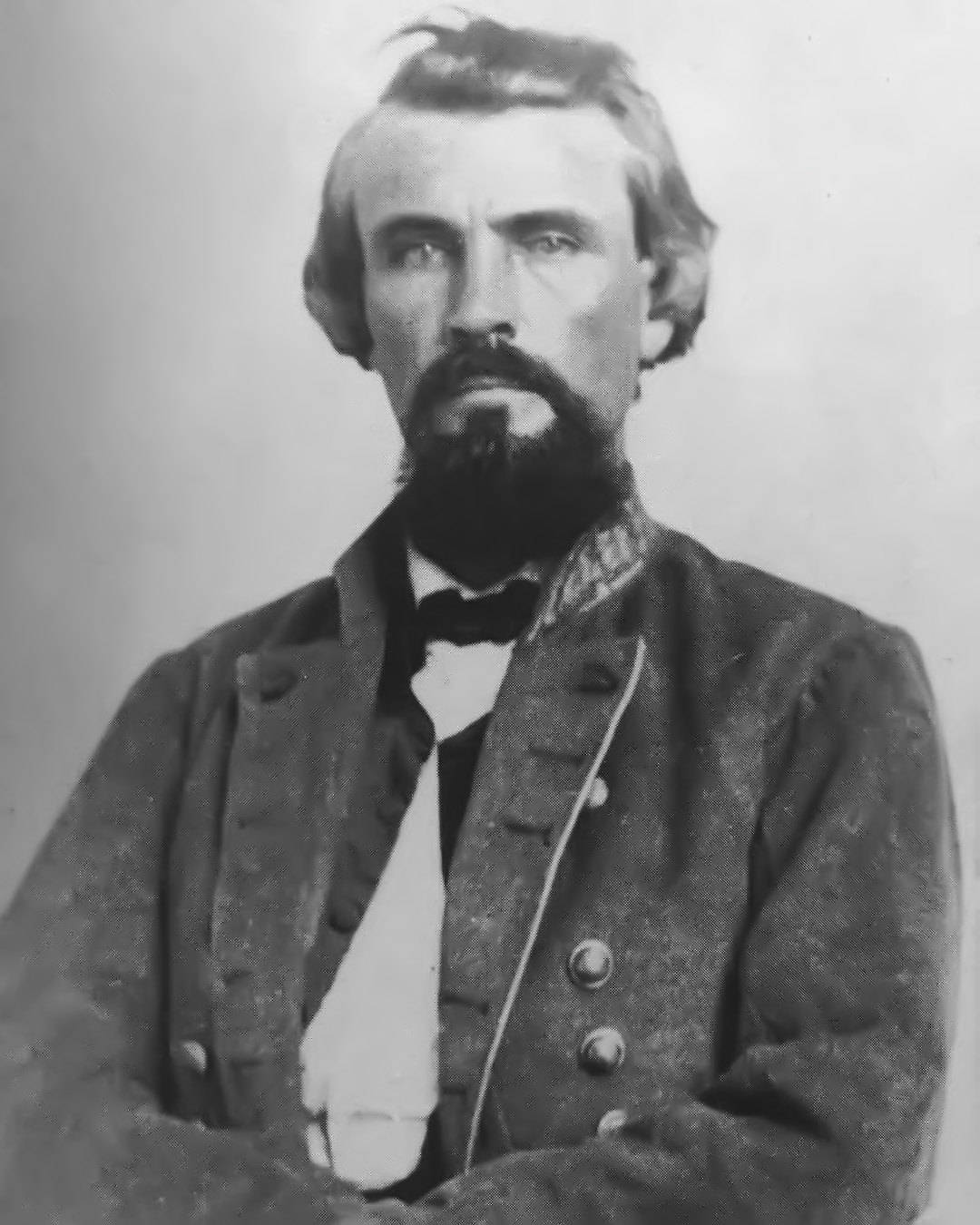

In May 1863 Forrest foiled Union Col. Abel D. Streight’s attempt to cut the Western and Atlantic Railroad, a vital supply line for the Confederacy’s Army of Tennessee. Later, Forrest joined that army in time to take part in the Battle of Chickamauga (September 19–20, 1863), where his command held the army’s right flank before pursuing the retreating Union forces. Following the battle Gen. Braxton Bragg, the Army of Tennessee’s commander, stripped Forrest of his command because the two had argued—one of numerous such acrimonious encounters Forrest had with superior officers during the war. Although Forrest had threatened Bragg’s life, Bragg, realizing Forrest’s importance to the Confederate war effort, never reported the incident. Forrest, on the other hand, refused to take any further orders from Bragg, but instead of accepting Forrest’s resignation, Confederate Pres. Jefferson Davis promoted him to major general.

Chickamauga Creek, Battle of Site of the second day of battle along the banks of Chickamauga Creek, near Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Forrest was tasked with raising, equipping, and training a new cavalry command to, again, operate semi-independently. With his fresh—if relatively untried—division, Forrest resumed his raids against Union forces. Soon he found himself embroiled in one of the war’s most controversial, and brutal, episodes. On April 12, 1864, Forrest’s command surrounded Fort Pillow, a small Union installation on the Mississippi River about 40 miles (65 km) north of Memphis. After failing to negotiate the fort’s surrender, Forrest ordered his men to take the outnumbered garrison (which was made up of African Americans, southern unionists, and Confederate deserters) by force.

The battle that ensued was characterized by close-quarters combat, chaos, and the almost total breakdown of command and control. Despite contradictory evidence regarding Forrest’s orders and response to the actions of his troops, it is clear that in many instances Forrest’s men killed African American soldiers who were attempting to surrender. During the battle and subsequent massacre, between 277 and 295 Union troops—most of whom were black—were killed. Although it was conducted by two Republicans (one of whom was a leading Radical Republican) and had clear propagandistic purposes, a congressional investigation committee verified the slaughter. Their report enraged the Northern populace, and “Remember Fort Pillow!” became a rallying cry for African American Union troops. Forrest achieved his most tactically impressive victory when he decisively defeated a numerically superior Union force at Brice’s Cross Roads, Mississippi (June 10, 1864).

Although this victory was strategically indecisive, it proved invaluable in cementing Forrest’s reputation, and throughout the year he conducted other successful raids in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama. After these expeditions, he rejoined the main Confederate Army of Tennessee—now commanded by John Bell Hood—in November to take part in its last major action, the Franklin-Nashville campaign (September 18–December 27, 1864). This campaign was a disaster for the Confederacy, and following the Battle of Nashville (December 15–16), Forrest fought a stubborn rearguard action to cover the retreat of the broken army.

This, in turn, led to Forrest’s being promoted to lieutenant general. Nevertheless, he found himself in command of fewer men, who were equipped with inferior horses and poorly supplied. His final task of the war was to prevent the incursion of Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson’s Union cavalry into northern Alabama. In this, he failed, and Forrest was defeated by Wilson at the Battle of Selma, Alabama (April 2, 1865). He surrendered his entire command in May. Forrest’s postwar business career was not as lucrative as his antebellum ventures. He had exhausted his fortune during the war, and with the abolition of slavery, he lost one of his most valuable avenues for making money. After serving as the president of the Selma, Marion, and Memphis Railroad, he settled on managing a plantation manned by convict labor.

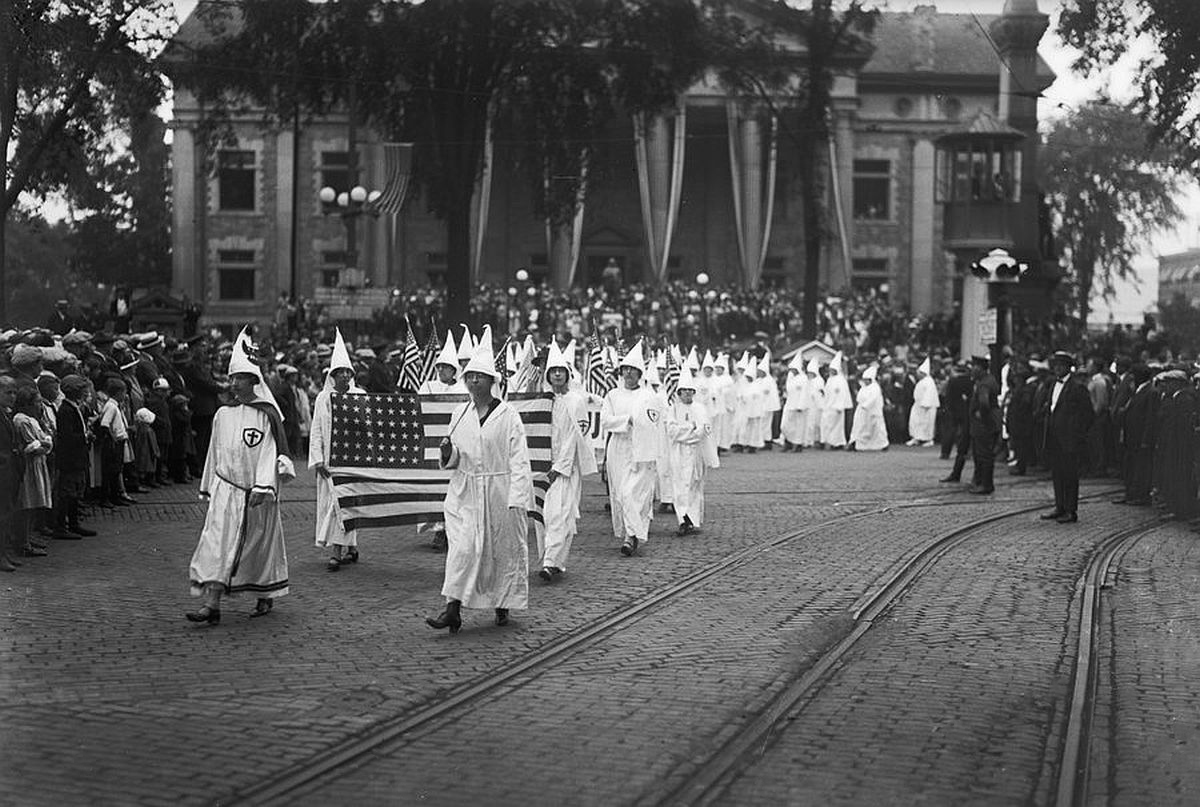

Forrest’s notoriety only increased when, in 1867, he became the first grand wizard of the original Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a secret hate organization that employed terror in pursuit of its white supremacist agenda. Although the extent of Forrest’s influence in the KKK is disputed, at the very least his prestige served to expand membership rolls. The KKK embarked upon a campaign of intimidation and violence against Southern blacks and Republicans until Forrest ordered the organization disbanded in 1869. Nevertheless, local chapters of the KKK continued to be active, and Forrest was ordered to appear before a congressional hearing in 1871. In his sometimes contradictory testimony, he denied membership in the organization. A combination of age, exhaustion, and conversion to Christianity seems to have caused Forrest’s fiery temper and racial attitudes to moderate in his later years.

Forrest has proved to be one of the Civil War’s most controversial figures. Unsurprisingly, given his culpability in the Fort Pillow Massacre and the formation of the KKK, Forrest and his image have come under attack by many sectors, especially African Americans. On the other hand, many white Southerners continue to admire Forrest for his wartime record, common-man origins, and masculine bearing. In recent decades Forrest has come to rival the less-controversial Robert E. Lee and Thomas (“Stonewall”) Jackson as the foremost human symbol of Confederate identity. Consequently, debates have emerged wherever Forrest has been commemorated. Schools, streets, and buildings named in the general’s honor have sometimes been renamed, and Health Sciences (formerly Nathan Bedford Forrest) Park in Memphis—the location of the general’s grave and a large equestrian statue of him—has been the focus of both KKK and civil rights demonstrations.