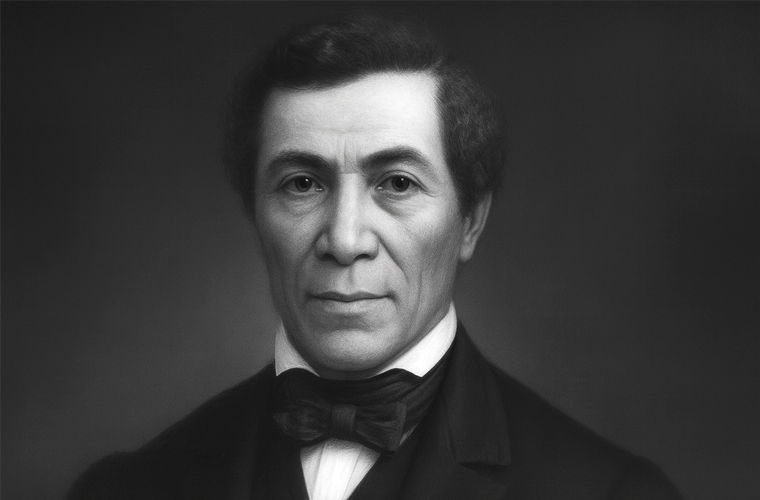

John Russwurm, born on October 1, 1799, in Jamaica, British West Indies, was the son of a Creole woman and a white American father. In 1807, his father returned to the United States, and young John was sent to Canada to receive an education. Later, his father’s new wife welcomed him into their home in Maine, ensuring he received a comprehensive education. This opportunity led him to Bowdoin College, where he graduated in 1826, becoming one of the first two Black individuals to earn a degree from an American college, a significant milestone in an era of widespread racial barriers.

In 1827, Russwurm embarked on a groundbreaking venture by co-editing Freedom’s Journal, the first newspaper published by and for Black people in the United States, alongside Samuel Cornish, another free Black man. Initially, the newspaper aligned with the views of many free Black intellectuals, opposing the American Colonization Society (ACS), which promoted the resettlement of Black Americans to Liberia. However, after Cornish’s departure, Russwurm’s perspective began to shift. By February 1829, he publicly endorsed colonization, a stance that alienated many of the paper’s Black subscribers. Their backlash, coupled with declining support, led to the newspaper’s collapse. Facing hostility, Russwurm chose to emigrate to Liberia later that year.

In Liberia, Russwurm quickly assumed significant roles. By 1830, he was appointed superintendent of schools and took on the editorship of the Liberia Herald, contributing to the colony’s intellectual and civic development. Elected as secretary of the colony by Liberian settlers, he served until 1836, when ACS officials in the United States dismissed him. Frustrated by this external interference and the denial of self-governance for Black settlers, Russwurm left Monrovia. He then became governor of Maryland-in-Liberia, a separate settlement backed by the Maryland Colonization Society, a position he held from 1836 until he died in 1851.

As governor, Russwurm demonstrated remarkable administrative skill and leadership. He governed with authority but also with wisdom, fostering peace with neighboring African communities, which was critical to the colony’s survival. He tackled complex challenges in finance, trade, agriculture, justice, and the establishment of representative government, while maintaining ties with American supporters. After Liberia declared independence in 1847, Russwurm worked to unify Maryland-in-Liberia with the larger Liberian republic. However, differences among settlers and their respective American sponsoring organizations prevented this unification during his lifetime.

Russwurm’s life was marked by intellectual achievement and a deep commitment to the advancement of the African race. He firmly believed in the equality of Black people and their right to self-governance, a conviction that shaped his decision to leave the United States, where he saw little hope for racial equality. His embrace of Black nationalism and his contributions to Liberia’s early development left a lasting legacy in African American and African history. Russwurm died on June 17, 1851, but his vision for self-determination and his efforts to build a thriving Black-led society in Africa endured, influencing future generations of Black leaders and thinkers.