American musician John Lee Hooker (1917-2001) was an influential blues artist who played a role in the development of the genre from the late 1940s through the 1990s. Playing both electric and acoustic guitar, Hooker’s distinctive vocal and instrumental style also shaped the development of rock and folk music during the 1960s and 1970s.

John Lee Hooker was born on August 22, 1917 (some sources say 1920), in Clarksdale, Mississippi, the fourth of 11 children born to William and Minnie Hooker. Hooker’s father was a sharecropper and Baptist minister who did not like the blues, referring to it as the “devil’s music.” Hooker’s parents separated when he was five and divorced when he was 11 years old. While Hooker received a limited formal education, music was an important component of his life. He first became exposed to it at church and constructed his first instrument out of a piece of string and an inner tube. Soon after her divorce, Hooker’s mother was remarried to William Moore, a blues musician. Hooker credited Moore with mentoring him as a musician.

Moore taught Hooker how to play guitar, showing the boy his minimalist but the very rhythmic style of playing. Soon Moore and Hooker were playing together at house parties and dances near their hometown. Though Hooker enjoyed playing with his stepfather he was unhappy living in Mississippi and when he was 14 years old he ran away from home.

Hooker first tried to join the U.S. Army, in part because during World War II a young man in uniform would attract the attention of women. He made it through basic training and after three months was stationed in Detroit before it was discovered that he was underage and he was kicked out. Hooker then moved to Memphis, Tennessee. Supporting himself with day jobs such as movie theater usher, Hooker also worked as a musician at house parties because he could not get into clubs. Among the musician, he played with was Robert Lockwood.

In his late teens, Hooker moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he continued to work menial day jobs as a dishwasher and steel mill worker while establishing his music career at night. Because he was still a minor, Hooker could only play the blues at house parties. However, he also sang in gospel quartets like the Delta Big Four, Fairfield Four, and the Big Six. By working frequently in front of a crowd, Hooker learned the ropes of performing on stage and entertaining an audience.

In 1943 Hooker moved to Detroit, where jobs were plentiful because so many men were overseas fighting in World War II. He held day jobs washing dishes and working as a janitor in a Chrysler automobile plant until 1951. Now a legal adult, Hooker was now able to perform at the many blues clubs located near Detroit’s Hastings Street.

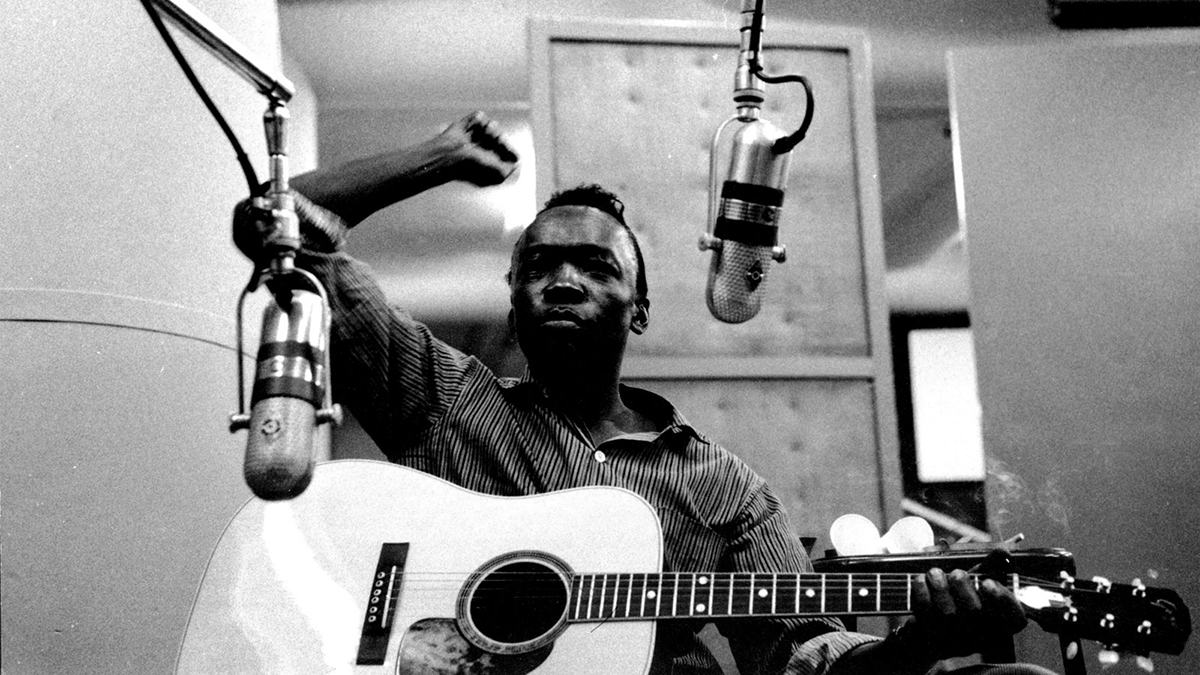

While living in Detroit Hooker’s style changed: from the country/rural folk-type blues played primarily on an acoustic guitar, he shifted to a more urban style played on an electric guitar. Part of the change was due to his encounter with Elmer Barber, a local record-store owner. Barber had heard Hooker perform and he made several primitive recordings of the young musician in the makeshift studio located in the back of his store.

Barber’s recordings soon found their way to Bernie Besman, owner of a small record label, Sensation Records. It was Besman who suggested that Hooker should switch to electric guitar and include faster-paced material in his gigs at local clubs. Taking this advice, Hooker soon became one of the leading musicians in Motor City, which at this time was witnessing a booming economy due to the men and women living there who had become wealthy due to the rise in wartime manufacturing.

Hooker made his first single for Besman in 1948. “Boogie Chillen,” recorded in a basement in Detroit, features only Hooker’s vocals, his electric guitar, and the sound of his foot tapping the beat. When “Boogie Chillen” was released on Sensation it sold so well that the small label could not handle the demand. The single was then released on Modern Records and quickly climbed to the number-one spot on 1949’s prototype R & B charts, selling a million copies.

Although Hooker did not receive the royalties he was entitled to for this and future songs, his success with “Boogie Chillen” came as a surprise to him. In 1949 he followed up his first single with ten other top-ten songs. Many of these early recordings feature only Hooker and his guitar, although fellow guitarist Eddie Kirkland sometimes appeared on recordings with him.

One reason that Hooker often recorded alone was that his beat was hard for accompanying musicians to follow. By recording alone, it was easier to achieve a clean take, and the recording session took less time. Describing his sound, Hooker once told John Collis of the Independent, “I don’t like no fancy chords. Just the boogie. The drive. The feeling. A lot of people play fancy but they don’t have no style. It’s a deep feeling—you just can’t stop listening to that sad blues sound. My sound.”

Despite becoming involved in conflicts regarding royalty issues, Hooker continued to record for Modern in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and some of his hits of the period include “Rock House Boogie,” “Crawling King Snake,” and “In the Mood.” One of his most popular recordings of the period, “In the Mood” was released in 1951 and sold a million copies. To ensure that he would earn enough to support his family, Hooker recorded and released material under several other names for over two dozen other labels. Some of his pseudonyms included John Lee Booker, which he used for Chess recordings, Johnny Lee, used for DeLuxe, and Texas Slim and John Lee Cooker, which he used on his recordings for the King label.

Many of Hooker’s early releases influenced other bluesmen such as Buddy Guy and are considered to be early precursors to rock and roll. His blues songs incorporated the traditional blues sound with jump and jazz rhythms. Although Hooker recorded his music with little backup, he also performed with a live band at clubs in Detroit and beyond. Due to his talent, hard work, and determination, Hooker was a success on the R & B circuit throughout the 1950s.

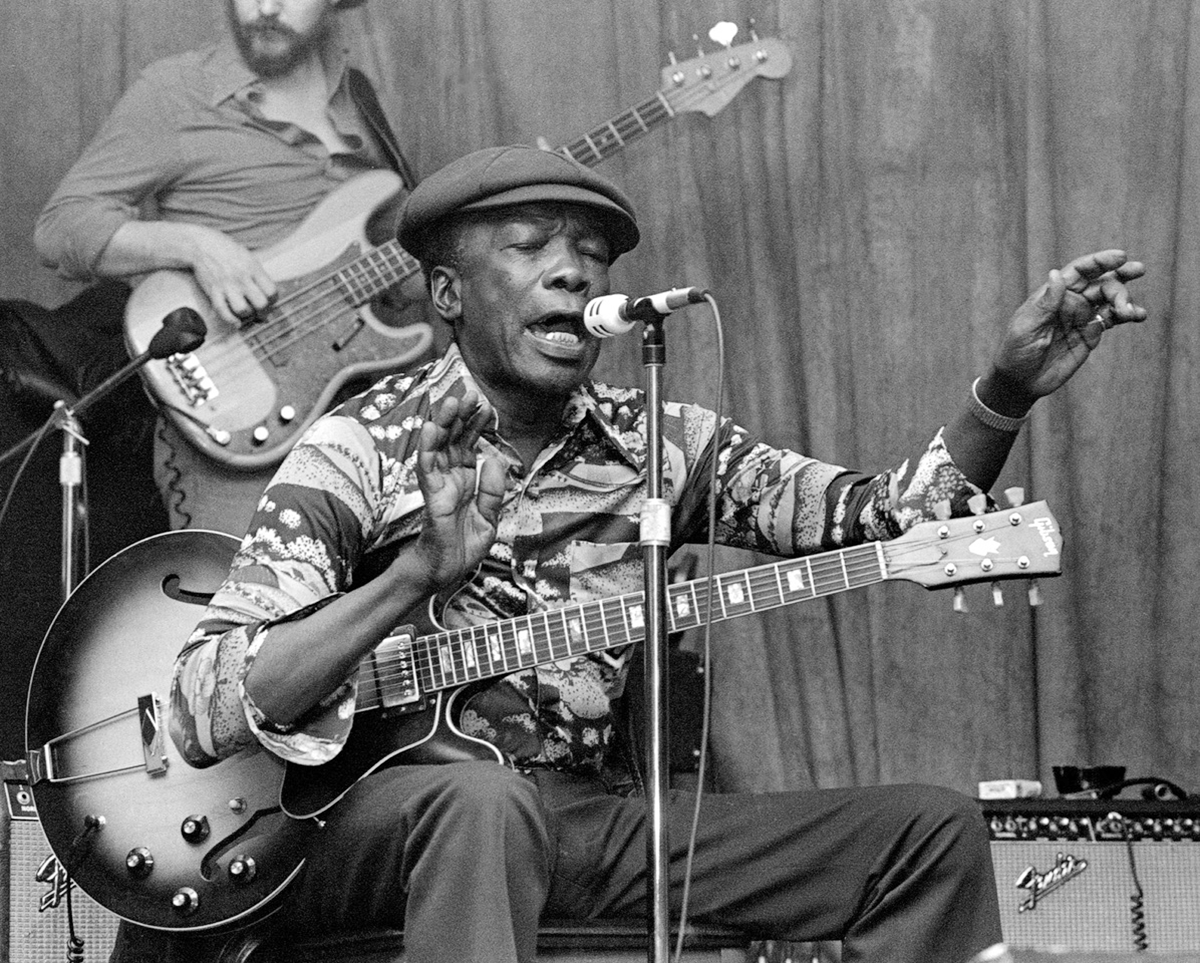

In 1955 Hooker signed on with VeeJay Records of Chicago. For this label he changed his recording style, his subsequent recordings becoming a better reflection of his live show. Because solo blues performance was waning in popularity, Hooker started recording with a band, producing such hits as “Dimples” and “Boom Boom.”

Even though Hooker found success performing on electric guitar, he discovered a new audience for his acoustic blues during the late 1950s. Folk music was now undergoing a revival of interest, and groups like the Weavers and blues singers like Odetta were increasingly becoming popular among young white college students. Hooker began appearing in folk clubs, coffeehouses, on college campuses, and at folk festivals as a solo artist and did several recordings accompanying himself with the acoustic guitar. Many of his songs written and recorded during this period reflect his background in Mississippi.

In 1959 Hooker released his first record album, I’m John Lee Hooker, on Riverside Records, his new label. This new turn in the career of the 42-year-old bluesman earned him an even wider audience, not just among white folk fans but in international markets where his records were also released.

Hooker once discussed his change from electronic band to solo folk music with Peter Watrous, telling the New York Times interviewer: “I played solo for a long time, so I know how to tap my feet so it sounds like a drum. It wasn’t any problem to start playing the coffeehouses. I can switch to any style, you have to be versatile as a musician. I knew the white audience was out there but I didn’t know how to get it. As the years go by, things changed and to me, they were just people. I had no thought that British singers would start singing my songs, I had no idea what would come with that. People got more civilized.”

In the 1960s Hooker began touring internationally, and the popularity of his music spread throughout the world, particularly among the more sophisticated audience. His songs also influenced emerging British rock bands such as the Rolling Stones and the Animals. Hooker continued to record on VeeJay, although he did not end his practice of laying down tracks for other labels as well.

By the mid-to-late 1960s Hooker once again moved away from performing acoustic solo blues when the trend toward electric blues prompted him to put together a new band. In 1965 he recorded an album with British group John Mayall and the Groundhogs. Many of Hooker’s recordings during the late 1960s were albums rather than singles, and many were recorded in collaboration with bands composed of younger musicians. While many of these recording sessions produced mixed results due to Hooker’s unique rhythmic stylings, his sessions with the group Canned Heat are considered one of the best. The resulting album, 1971’s Hooker ‘n’ Heat, was a hit.

Though Hooker continued to record a little and play a lot during the late 1970s and 1980s, the blues had declined in popularity, and demand for his music had declined. He still toured as a way to pay the mortgage on the house he owned in San Francisco, often performing with his Coast-to-Coast Blues Band and sometimes coming under fire for letting other musicians carry him musically. Many of his early recordings were also repackaged and released for blues collectors.

Considered one of the top blues performers in the United States, Hooker was given a small role in the blockbuster movie The Blues Brothers in 1980. That same year he was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame. In the late 1980s and 1990s, his songs regained popularity, even appearing as part of film soundtracks. In the 1990s, Hooker himself began appearing in ads for Lee Jeans, Pepsi, various brands of liquor, and other products.

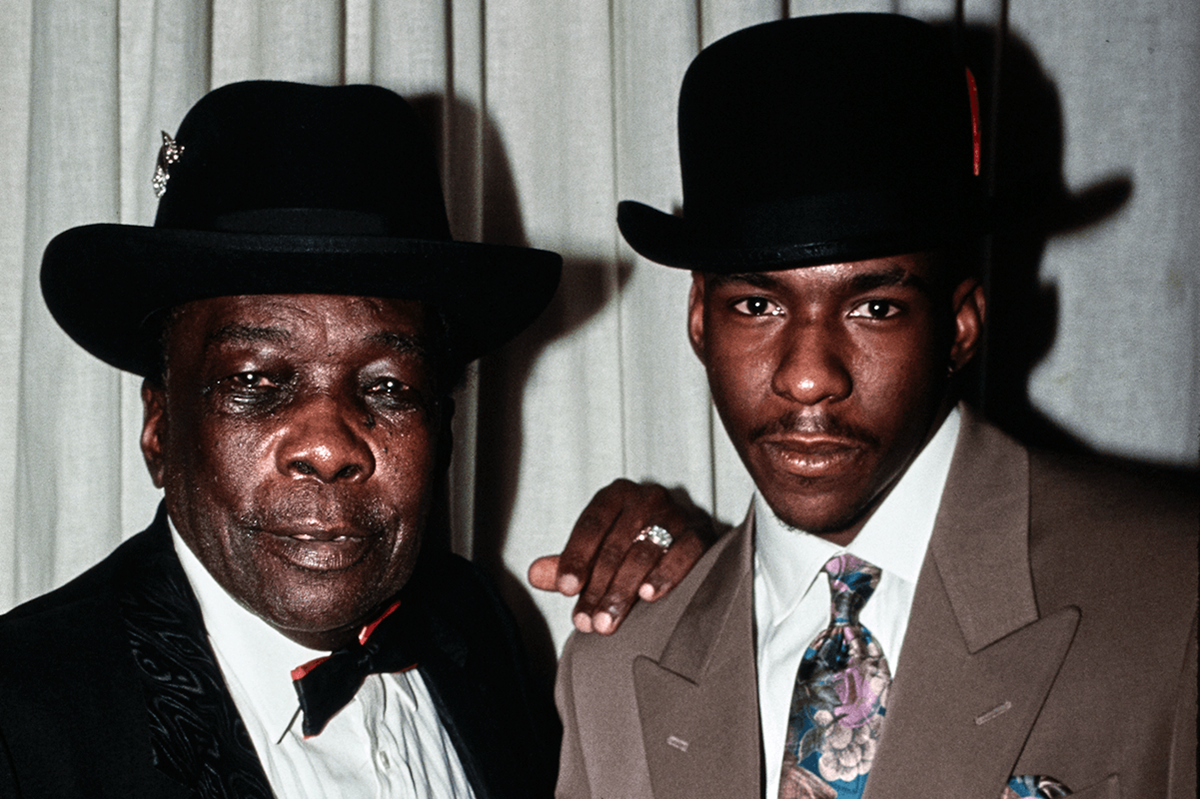

In 1989 Hooker returned to the studio after a decade’s absence and recorded The Healer. He was joined by several contemporary blues artists, including Bonnie Raitt and Robert Cray, as well as Latin artists Los Lobos and Carlos Santana. Produced by Hooker’s former guitarist Roy Rogers, The Healer became one of the biggest-selling blues records of all time, selling 1.5 million copies. Hooker also won a Grammy Award for the song “I’m in the Mood,” which he performs on the album with Raitt.

Hooker was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990 and was the focus of a tribute concert at Madison Square Garden that same year. With the success of The Healer, he started recording again, again in collaboration with other blues artists. His 1991 recording Mr. Lucky was a hit on the album charts in the United Kingdom. Among the musicians he worked with on this recording were Johnny Winter, Keith Richards, Van Morrison, and Santana.

Hooker continued to perform and record into his late 70s and early 80s and found himself even more popular now than he had been earlier in his career. He continued to perform live with the Coast-to-Coast Blues Band into the 1990s but had the added security of royalty income to rely on. Unlike many other blues and R & B artists of his generation, Hooker continued to earn royalties from his early recordings because he had wisely saved his contracts and, with the proper legal advice, went to court to ensure that recording companies continued to honor them.

After a hernia operation in 1994 made it painful for Hooker to perform, he slowed down. After the release of Chill Out in 1995, he retired from performing on a regular basis, although he still made occasional appearances on stage. In 1997 he opened a blues club in San Francisco called John Lee Hooker’s Boom Boom Room. One of his final releases was the album Don’t Look Back (1997), which features a cover of Jimi Hendrix’s “Red House.”

Hooker died in his sleep of natural causes on June 21, 2001, at his home in Los Altos, California. He had performed five days earlier and was making plans to return to the recording studio. At his death he had recorded more than 500 tracks, making him one of the most recorded blues musicians of all time. Married and divorced four times, Hooker was survived by eight children. Late in his life, he had contemplated his eventual passing, telling Ben Wener of Tulsa World: “We all got to go one day. We live out this life as long as we can and try to make the best of it. Simple as that. That’s what I’ve done. All my life, just try to make the best of it.”