Daviess County sheriff Florence Thompson had held the position for only a few months when the Rainey Bethea case landed on her desk. Bethea had confessed to the rape and murder of 70-year-old Lischia Edwards — a capital crime under Kentucky law, and one that fell upon the local sheriff to punish. “I could appoint the deputy sheriff or deputize any citizen to spring the trap,” Thompson told reporters as she stoically resigned herself to the role, “but to do that would inflict an unpleasant job … upon someone else.” She would be the country’s first female executioner, and the press ate it up.

By then most states had long since abandoned the practice of public executions. But this “hangman in skirts” had aroused in readers a deep curiosity, like some medieval muscle memory of a time when grotesque civic entertainment was customary. Bethea’s guilt, let alone the ethics of public execution, hardly came into question for the dozens of newspaper articles leading up to the August 14 hanging.

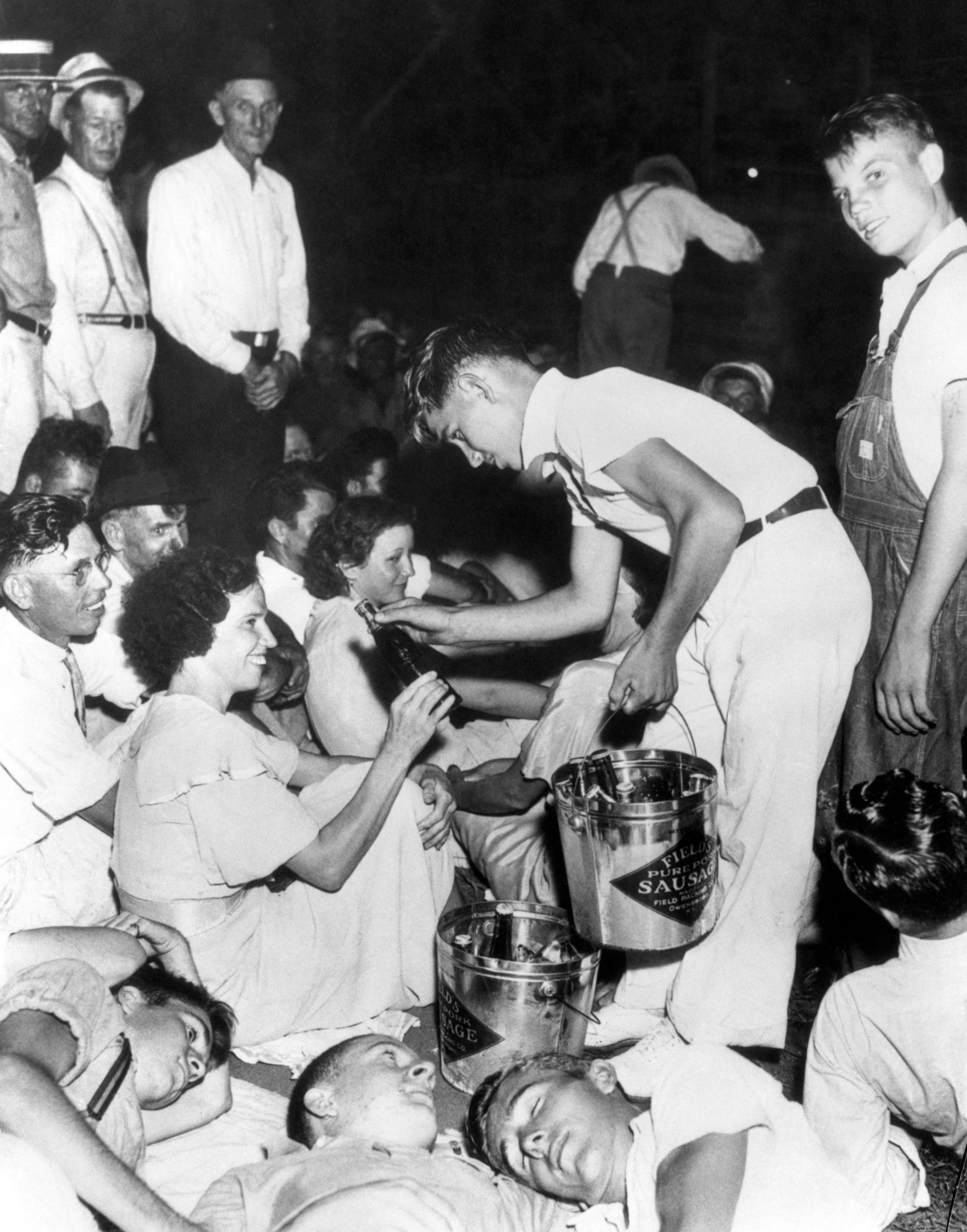

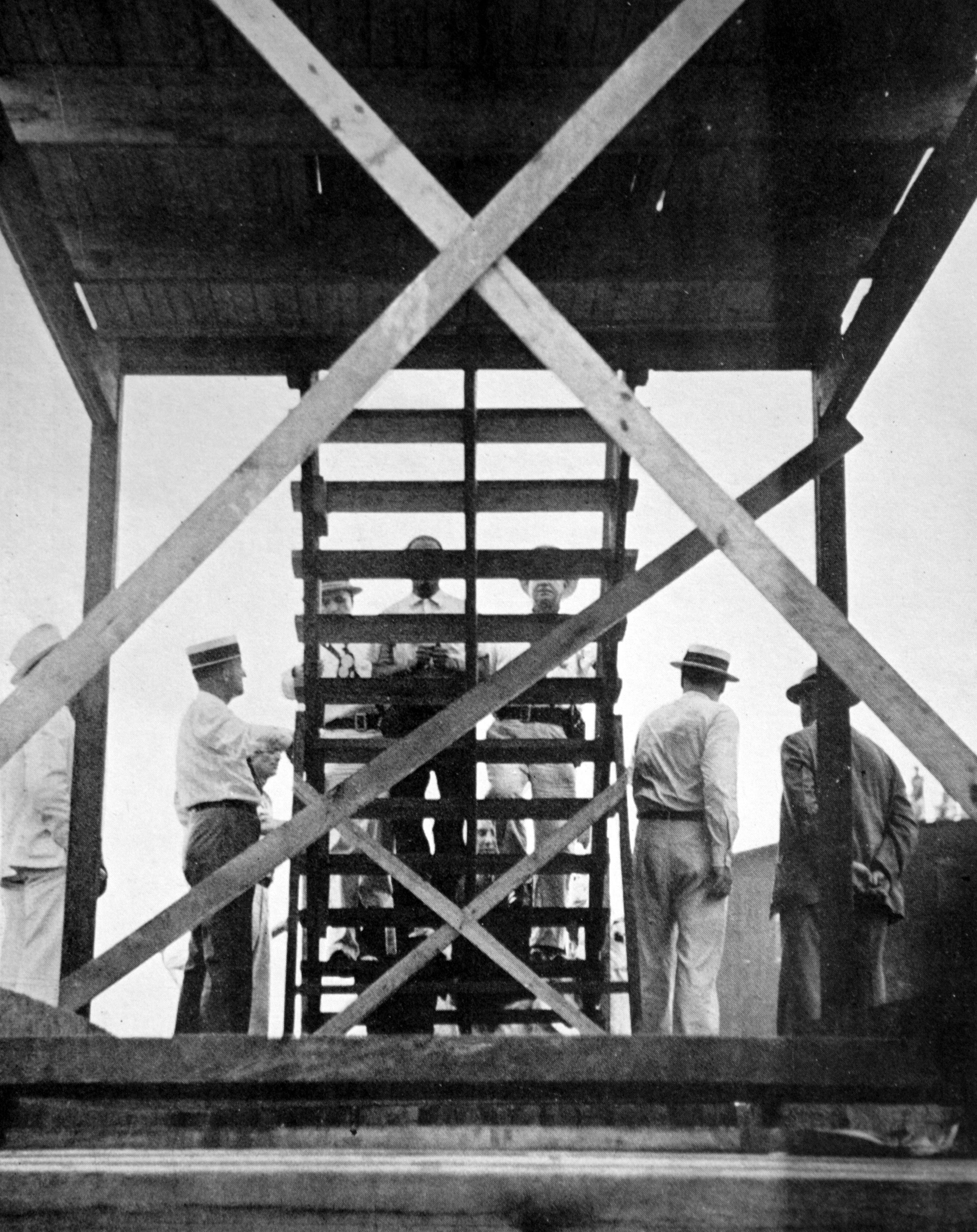

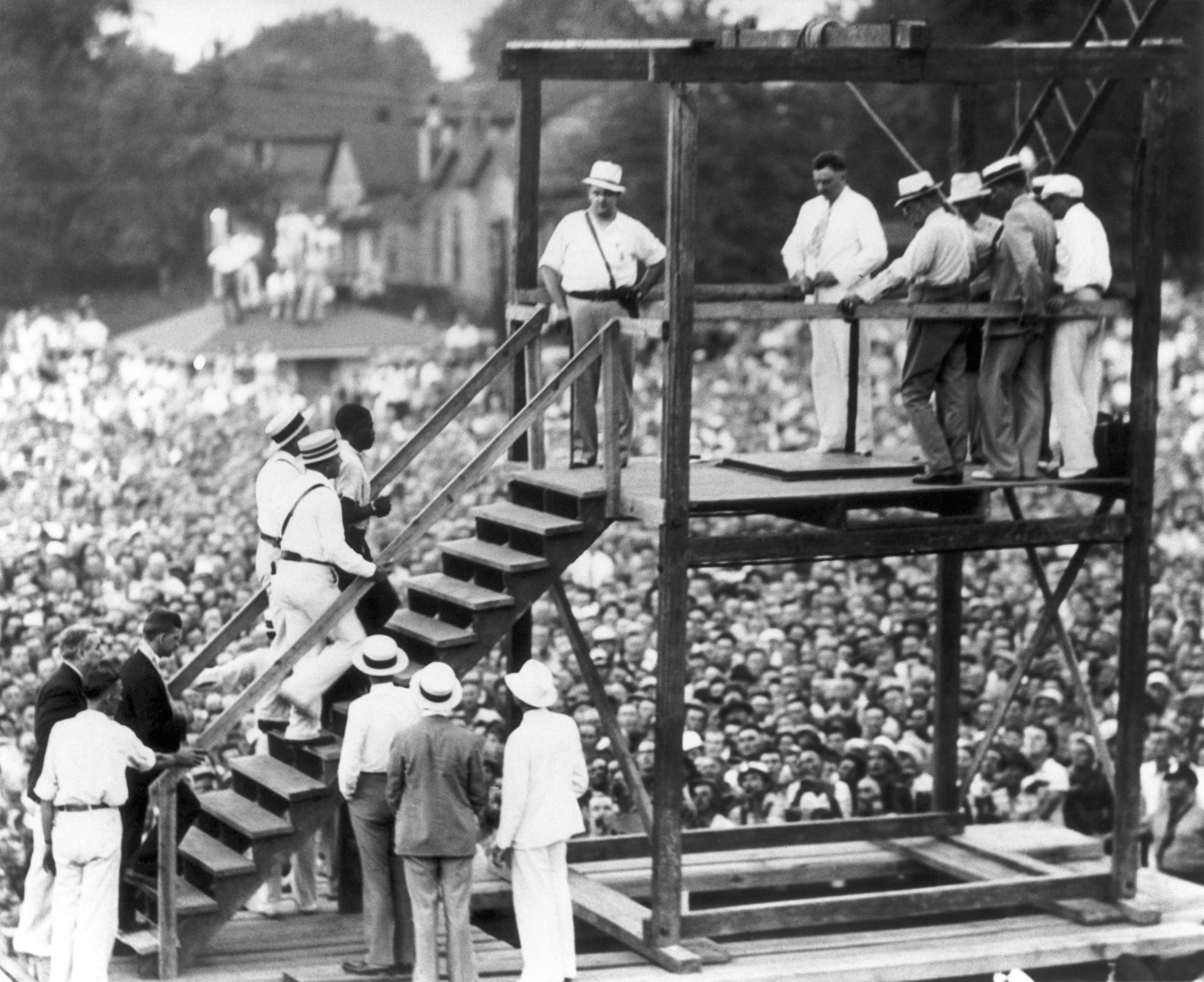

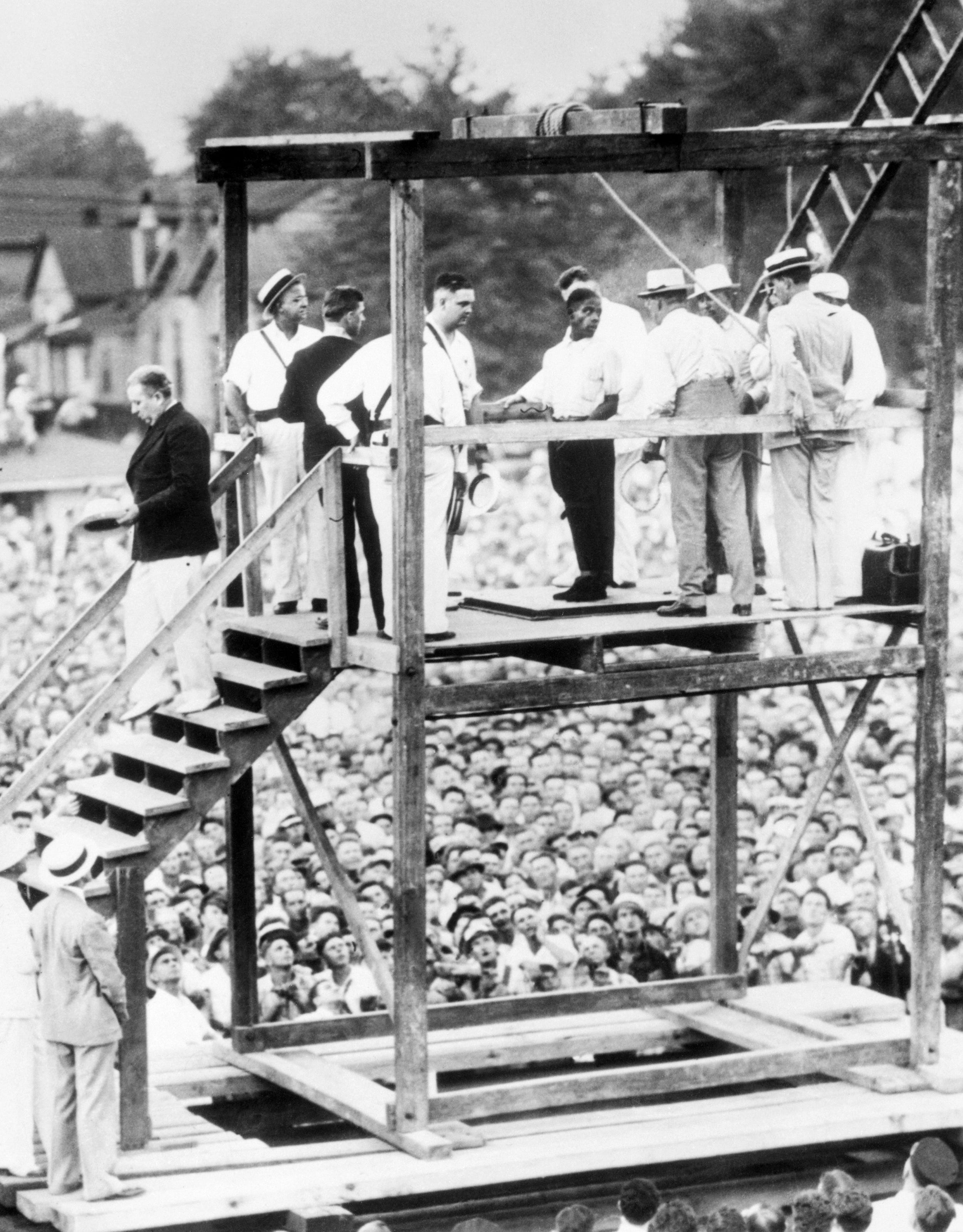

Upwards of 20,000 people were in attendance as Bethea ascended the gallows. To their surprise, Thompson didn’t go through with it. Instead, a pair of eager volunteer hangmen were chosen for the grim task of setting the noose and “pulling the trap.” Robbed of their story, a legion of newsmen took instead to descriptions of the rapacious onlookers, many of whom had camped out overnight, intent on an unobstructed view of Bethea’s end. Inflating the grim attraction of another man’s agony, the Santa Rosa Press Democrat described a “carnival atmosphere” of spectators “who munched hot dogs and sipped lemonade as Bethea dropped through the trap.” Other papers reported on the “all-night ‘hanging parties’” hosted by locals. Hotels were full to capacity.

For all its hype and uncertainty, the Bethea case illustrates a fascinating confluence of mores and morals surrounding death, punishment, race, and gender roles in interwar America. Surely, the intensity of press covering Bethea’s hanging came to bear on Kentucky’s decision 18 months later to abolish public executions. Sheriff Thompson, who, wittingly or not, opened the door for that attention, catalyzed a situation that led to blanket coverage of the hanging, in turn exposing to a national audience the morbidity of a spectacle already seen by many as outdated. Nary a reporter praised what he saw in Owensboro that summer and the world soon had a clear, impassioned picture of mob voyeurism at its worst.