The number of European and American merchants, shipbuilders, and investors directly involved in the transatlantic slave trade over a period of more than 350 years was immense. The system they designed in collusion with African coastal traders and those involved in auxiliary trades in Europe, Africa, and the Americas created far-reaching and ever-shifting tentacles of exchange that swept African individuals from their villages into international commerce that placed them in new worlds as commodities. Through creativity, resilience, and faith, survivors of the Middle Passage and their descendants forged meaningful lives circumscribed by the oppressive societies in which they found themselves.

It is difficult to imagine that a system that once treated human beings as commodities—with price tags—was not only legal, but was considered to be ethical and a major source of wealth, influence, and respectability for many. By the early seventeenth century, however, the transatlantic slave trade was a sophisticated commercial system that hinged on the availability of captives transported to the coast by African traders deep in the interior of the continent. Some African captives were sold multiple times and detained for months in markets or barracoons along interior slave routes before encountering European slave ships on the coast. Only after an already perilous passage from the interior were survivors exchanged for a combination of textiles, weapons, alcohol, or other European trade goods and loaded aboard large canoes that took them to slave ships anchored off the coast.

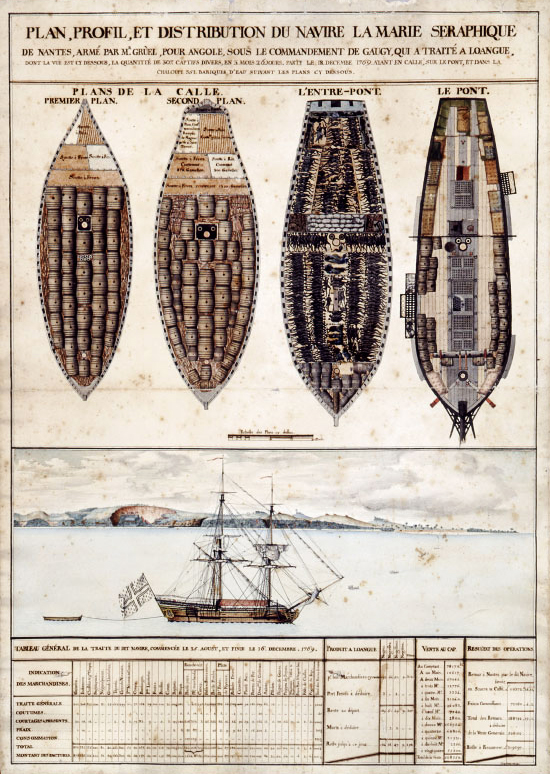

A slave voyage was always a risky financial venture for the owners and investors. Though they planned for all eventualities, everything could be thrown into turmoil by bad weather, poor navigation, slave uprisings, and other physical dangers. Also, the nature of trade along the African coast was ever-changing, as the desirability and value of particular textile designs and colors, for example, varied month by month and from region to region. Moreover, exposure to tropical diseases invariably reduced the European crewmen’s numbers on the coast and at sea. For these investors, the most serious of all was the loss of captains, surgeons, experienced sailors, and the human “cargo.” The ship captains drafted both experienced and inexperienced sailors, which created risks for the ship owners and investors. Slave ships were, then, dangerous, violent, and disease-ridden.

Despite the risks, slave voyages proved to be greatly profitable for their investors. The ship captain faced a paradox because it was in the crew’s interest to ensure that as many African captives survived as possible in order to be sold to the highest bidder in the Americas. The slavers’ and their investors’ aim was to sell the men, women, and children for the best prices, not to kill or disable them, but the crew often resorted to violence to control and demoralize the captives.

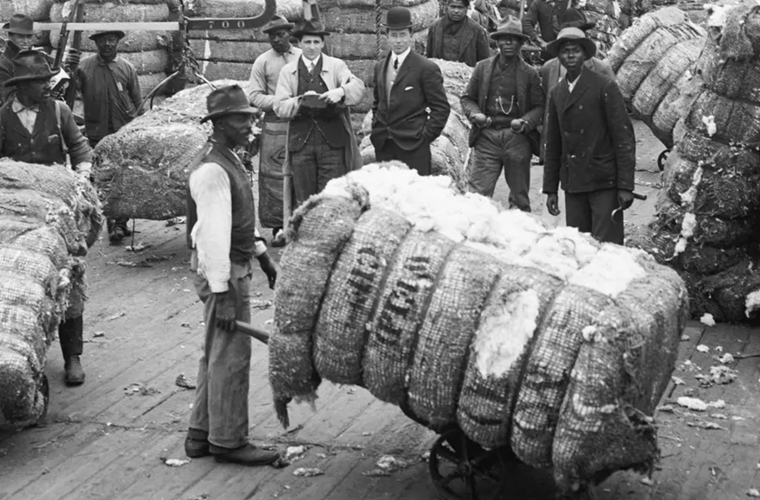

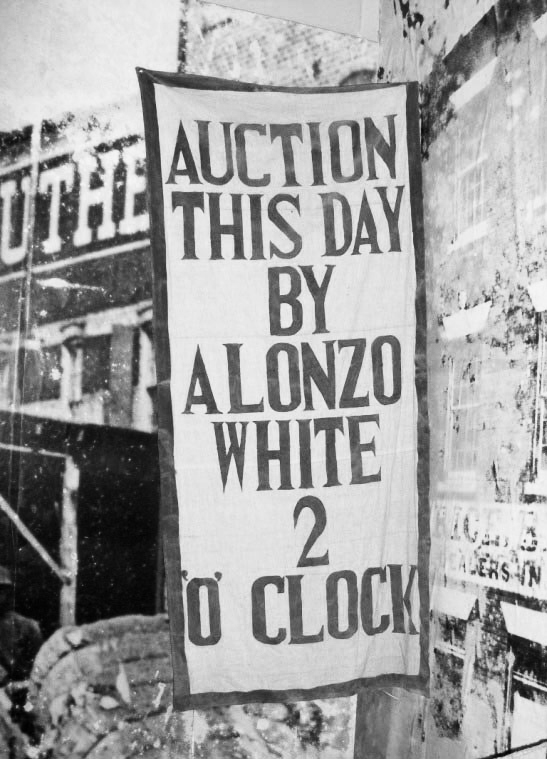

Sighting land in the Americas was a relief for the captain and crew but must have brought new uncertainty and fear to those who had survived the Middle Passage. After the captain landed the ship in a port, African survivors were inventoried, fed, scrubbed, and oiled to create a healthier appearance. The crew used a variety of methods to disguise the physical bruises and wounds on the African captives’ bodies, in order to hide their ailments and yield the highest prices possible.

Slave traders sold enslaved people in a variety of ways. Some traders delivered Africans directly to merchants who had placed orders with the shippers. Other Africans were sold on auction blocks to the highest bidders in major ports like Port-au-Prince, Bridgetown, or Salvador de Bahia. For many Africans, the terrifying ordeal was the “scramble,” where purchasers raced among the assembled captives, grabbing and claiming the ones they wanted.

Arrival in the Americas did not mean the end of an enslaved person’s journey. The Caribbean islands were typically the first landing for many Africans before the ship captains sent them off on another voyage, to the slave markets on the mainland of North, South, or Central America. In this way, an extensive inter-coastal American slave trade existed, linking the business and shipping interests of Caribbean merchants with those in North, South, and Central America.

In Brazil, for example, newly-arrived Africans faced re-sale, followed by an onward march to distant settlements and plantations. In the Caribbean as well, slave ship captains often shipped Africans to other islands, including Spanish colonies in Central and South America and even slave markets along the Pacific coast.

When their maritime journeys ended, Africans were moved on, yet again. African survivors who arrived in Jamaica and Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), were marched deep into the mountainous and wooded interior to develop new properties or replace enslaved people who had died from harsh labor and living conditions. In North America, local slave traders marched Africans over land, to be sold to property owners in the developing backcountry of the Carolinas. In the nineteenth century, their descendants were to be uprooted and moved yet again to the new cotton and sugar frontiers of the southern United States.

From capture in Africa to their final sale in the Americas, enslaved people experienced loss, terror, and abuse that challenged even the strongest-willed and most resilient among them. At every point of this horrific journey, the business of the slave trade and the enslaved individual’s role as a commodity was present. Exchange, trade, and profits were the engines of the transatlantic slave trade—a trade that yielded profits and bounty for western Europeans and American colonists on a remarkable scale for nearly four centuries.