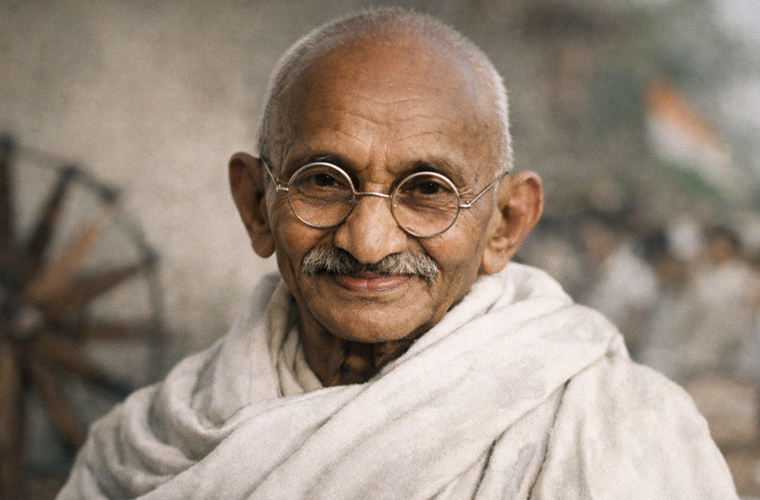

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, revered as the “Mahatma” (Great Soul) and the Father of the Indian Nation, was a transformative leader whose philosophy of nonviolent resistance, or satyagraha, inspired global movements for justice and independence. Born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Gujarat, Gandhi trained as a lawyer in London before facing the harsh realities of racial discrimination in South Africa, which ignited his lifelong commitment to civil rights. Returning to India in 1915, he spearheaded the Indian National Congress’s push for swaraj (self-rule), orchestrating iconic campaigns like the 1930 Salt March and the 1942 Quit India Movement. His advocacy for ahimsa (nonviolence), religious harmony, and social reforms—such as eradicating untouchability and promoting women’s rights—mobilized millions against British colonial rule, culminating in India’s independence on August 15, 1947. Gandhi’s influence extended far beyond India, shaping leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. Yet, his legacy is not unblemished. In recent years, protests in South Africa, Ghana, and the United States have spotlighted allegations of racism in his early writings and actions, particularly during his two decades in South Africa (1893–1914). These revelations challenge the hagiographic portrait, urging a reckoning with a man who, while evolving toward universal equality, began his activism by reinforcing racial hierarchies.

The Making of a Satyagrahi: Early Life and Arrival in South Africa

Gandhi’s journey to activism began humbly. After a brief, unsuccessful stint in legal practice in India, he arrived in Durban, South Africa, in 1893 at the age of 24, representing an Indian firm. Almost immediately, he encountered the sting of colonial racism: ejected from a first-class train compartment despite a valid ticket, an incident that crystallized his resolve. This experience fueled his founding of the Natal Indian Congress in 1894, a platform to fight discriminatory laws targeting Indians, such as poll taxes and pass requirements. Over the next two decades, Gandhi organized strikes, boycotts, and peaceful protests, refining satyagraha as a tool of moral persuasion. He volunteered Indian stretcher-bearers in the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) and the Bambatha Rebellion (1906), earning respect from British authorities while building alliances within the Indian diaspora. His newspaper, *Indian Opinion*, became a voice for self-reliance and ethical living, drawing from influences like Leo Tolstoy and the Bhagavad Gita. By 1914, his efforts had secured concessions for Indians, paving the way for his return to India as a seasoned strategist.

Yet, beneath this narrative of principled resistance lies a troubling undercurrent. Gandhi’s early activism was narrowly focused on elevating Indians within the colonial racial order, often at the expense of Black Africans, whom he derogatorily termed “Kaffirs“—a slur evoking savagery and inferiority. Influenced by Victorian-era racial theories and his own Hindu cultural lens, he viewed Indians as a civilized “middle class” between whites (with whom he sought “Aryan brotherhood“) and Africans, whom he portrayed as primitive and incapable of self-governance.

Unpacking the Racism: Quotes and Actions That Stain the Record

Gandhi’s writings from this period, collected in The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, reveal attitudes that today read as overtly racist. In a 1893 petition to the Natal parliament, he lamented that Indians were perceived as “a little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa,” positioning them as marginally superior but still degraded by association. This framing wasn’t mere rhetoric; it informed his entire campaign strategy. During the 1904 Johannesburg plague outbreak, Gandhi urged health officials to “withdraw Kaffirs” from the “Coolie Location,” a slum shared by Indians and Africans, confessing he felt “most strongly” about their “mixing.” He contrasted Indians favorably, noting they had “no war-dances, nor does he drink Kaffir beer,” implying Africans’ cultural practices rendered them unclean and disruptive.

These sentiments echoed in his advocacy for segregation. In 1896, Gandhi penned a pamphlet arguing that Indians, as a “civilized nation,” should not be lumped with “barbarous” Africans under the same racial laws, suggesting separate facilities like post offices to maintain this distinction. He supported a whites-only volunteer corps during the Boer War, excluding Africans, and turned a blind eye to the brutal suppression of Black communities in the Bambatha Rebellion, even as he treated some African patients in his clinic. Critics like historians Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed argue this made Gandhi a “junior partner” in white supremacy, accepting minority rule and higher taxes on impoverished Africans while prioritizing Indian validation. In an open letter to colonial authorities, he invoked shared “Indo-Aryan” roots with Europeans to demand better treatment for Indians over “savages,” explicitly reinforcing a hierarchy where Africans languished at the bottom.

Such views weren’t isolated slips but reflective of a broader strategy: carving out Indian exceptionalism in a system designed to divide and conquer. Gandhi’s early Indian Opinion editorials often erased African history, portraying them as interlopers rather than the land’s indigenous stewards, an erasure that aligned with imperial narratives.

From Prejudice to Pan-Humanism: Gandhi’s Evolution

To his credit, Gandhi was not static. By the late 1900s, exposure to broader injustices—through his 1906 vow of nonviolence and the establishment of Tolstoy Farm in 1910—began shifting his perspective. His newspaper started critiquing African dispossession, and the 1913 Great March, involving 2,000 Indian miners (including women), indirectly bolstered anti-pass campaigns that benefited Black workers. By 1914, Gandhi articulated demands for “universal equality and dignity,” foreshadowing his later embrace of non-racial solidarity. Biographers like Ramachandra Guha note that comprehensive anti-racism was “premature” in early 20th-century South Africa, where even progressive whites held similar biases; Gandhi, they argue, was “more radical than most contemporaries.” In India, his philosophy matured into a call for interfaith harmony and upliftment of the marginalized, influencing global anti-colonialism.

Defenders, including his grandson Rajmohan Gandhi, portray him as an “imperfect human” whose Indian struggles laid the groundwork for Black rights, evolving from ignorance to enlightenment. Yet, as Al Jazeera columnist Arundhati Roy-like voices contend, this evolution doesn’t absolve the harm; it demands we confront how his early racism perpetuated hierarchies that outlived him.

Modern Reckonings: Statues Toppled, Conversations Ignited

Gandhi’s racial blind spots have fueled contemporary backlash. In 2015, South African students at the University of Cape Town daubed his statue with “Racist Gandhi must fall,” citing his role in entrenching apartheid’s foundations. Similar protests erupted in Ghana (2018) and California (2021), where activists argued venerating Gandhi without context whitewashes colonialism’s intersections with anti-Blackness. These movements echo broader calls, as in Desai and Vahed’s The South African Gandhi, to “write Africans back into history” rather than sanitize icons.

| Key Controversies | Examples | Modern Response |

|---|---|---|

| Derogatory Language | Use of "Kaffir" for Africans equates them to "savages." | Petitions to remove statues in Ghana, South Africa |

Segregation Advocacy | Separate facilities for Indians to avoid "mixing" with Africans | Student protests labeling him "architect of apartheid" |

| Alliance with Colonizers | Boer War service; ignoring African brutalization | Critiques in U.S. Black Lives Matter contexts |

| Evolutionary Defense | Later non-racial campaigns; global influence | Calls for "complicated legacy" plaques on monuments |

.

Mahatma Gandhi remains a colossus of moral courage, his nonviolence a beacon against oppression. But highlighting his racism isn’t iconoclasm—it’s essential to honoring the complexity of change. As a young man in South Africa, he internalized and amplified colonial prejudices, viewing Black Africans through a lens of superiority that betrayed his later universalism. This duality reminds us: heroes are forged in fire, but their flaws endure as warnings. In an era of resurgent nationalism and racial reckonings, Gandhi’s story compels us to celebrate progress while dismantling the pedestals built on partial truths. True satyagraha begins with unflinching honesty about our pasts—Gandhi’s included.