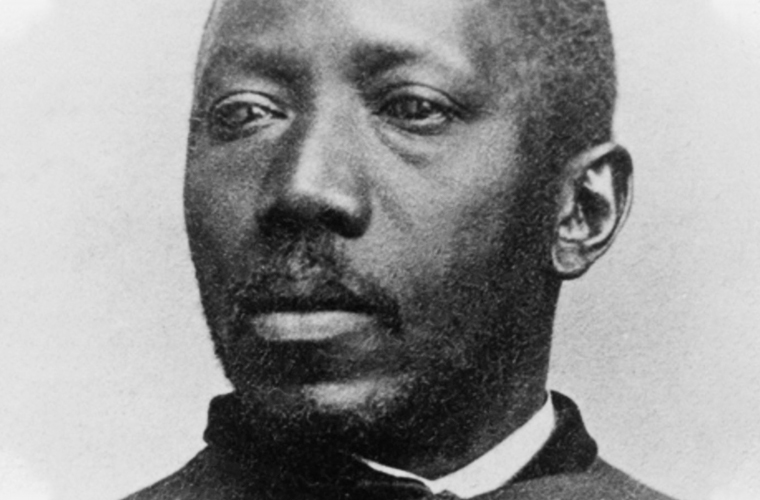

During the Civil War, Martin Robison Delany was a vigorous proponent of African American participation in the military defense of the nation, and he became the highest-ranking African American officer of a field regiment during the war in U.S. military history. Prior to this success, he broke color barriers through his academic studies, journalism, and his leadership in abolitionism.

Delany was born in Charles Town, Virginia, on May 6, 1812, to mother, Pati, a free-born African, and father, Samuel, an enslaved laborer. Although Virginia had begun to outlaw the education of blacks by the early 1820s, Pati was insistent on teaching her children how to read. When a white neighbor overheard Martin and his siblings reading and reciting the alphabet, Pati was forced to uproot her family and move to Pennsylvania in 1822 to allow her children educational opportunities. Samuel was unable to join his family in Pennsylvania for nearly a year until he bought his freedom.

At 19, Delany set out on his own for Pittsburgh to attend the free school for Blacks at Bethel Church. The oldest black congregation in Pittsburgh, Bethel had opened a school for its members under the pastorate of Reverend Lewis Woodson, funded by the African Education Society.

Delany was increasingly involved in the abolitionist and civil rights causes, attending Negro conventions, leading the Vigilance committee that helped fugitive slaves move and settle, and helping form the Young Men’s Literary and Moral Reform Society, which eventually turned into the Philanthropic Society as its activism increased.

In the late 1830s, Delany took part in defending the black community of Pittsburgh from white mob attacks when he joined Mayor McClintock in an integrated militia. He was one of the signers of a resolution defending the suffrage of African American men in Pennsylvania in 1837 that was defeated by a suit that effectively stripped the voting rights from blacks until 1871. He traveled down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, Texas, and then Arkansas where he visited the Choctaw Nation and was enlightened on the plight of African Americans in terms of free lands to settle and inspired to write the novel Blake: Or the Huts of America.

In 1843 he married Catherine Richards, daughter of Charles Richards, an affluent meat provisioner, and landowner. After having 11 children, he began to study medicine again and founded the Mystery newspaper. It was the first African American paper published west of the Allegheny Mountains, and it helped spread the word of the abolitionist cause.

After reporting the Pittsburgh fire of 1845, Delany was sued for libel by an African American named Fiddler Johnson. Delany was found guilty of libel in reporting that Johnson was implicit in helping slave catchers in Pittsburgh. Delany’s colleagues in the abolitionist community and journalism profession helped pay the fine of $650, but the resulting damage meant Delany had to sell The Mystery sheet to the African Methodist Episcopal Church where it was published as the Christian Recorder. In 1847, Delany joined Frederick Douglass in his newspaper The North Star, but due to differences in opinion on the way blacks were being treated, Delany left the paper five years later.

Delany enrolled at Harvard College Medical School in 1850 but within a few months was asked to leave following a petition presented by his fellow white students that demanded his expulsion. The following year he was back in Pittsburgh facing the black flight due to the Fugitive Slave Act, which forced abolitionists to consider new strategies for African Americans. The Fugitive Slave Act was a provision of the Compromise of 1850 to appease Southern slaveholders. Delany turned to emigration ideas, chairing the National Emigration Convention, and became a central figure in the effort to establish African American settlement in Canada, West Africa, and the Caribbean.

Delany resumed his writing, and in 1852 he published The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States Politically Considered, a treatise on the subject of emigration. The book was reviewed in William Howard Day’s The Alien American newspaper in 1853. He also published a sheet called The Origin and Objects of Ancient Freemasonry; Its Introduction into the United States and Legitimacy Among Colored Men.

In the mid-1850s Delany left Pittsburgh for Canada, met with John Brown in Chatham in 1858, and left for Nigeria to negotiate land for African American emigrants. Only the Civil War brought Delany back to America, and he joined others in proposing the use of African Americans in the Union Army. He recruited Blacks for the cause, even enlisting his son Toussaint L’Ouverture in the Massachusetts 54th regiment.

In February 1865, he met with President Lincoln at the White House to discuss African American officers commanding African American troops. He was commissioned a Major in the 104th regiment of the United States Colored Troops and served until the end of the war, making him the highest-ranking African American officer in U.S. history.

After the war, Delany worked for the Freedmen’s Bureau and Liberian Exodus Joint Stock Exchange Company. By 1879, he had published Principia of Ethnology: The Origin of Races and Color with an Archeological Compendium and Egyptian Civilization from Years of Careful Examination and Enquiry in Philadelphia. He returned to Wilberforce, Ohio, with his family where he died on January 24, 1885.