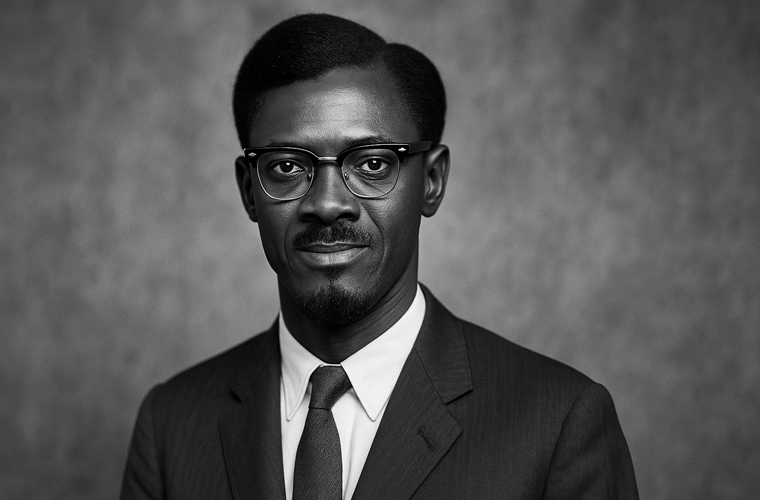

Patrice Émery Lumumba (1925–1961) was a towering figure in the struggle for African independence, serving as the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) after its liberation from Belgian colonial rule. Born into a modest family in the heart of the Belgian Congo, Lumumba rose from a postal clerk to a charismatic nationalist leader whose vision of pan-African unity and anti-imperialism inspired millions. His brief tenure in office, marked by bold reforms and fierce opposition to neocolonial interference, ended in tragedy amid the chaos of the Congo Crisis. Lumumba’s assassination cemented his status as a martyr for decolonization, though his legacy remains a flashpoint in Congolese and global history.

Patrice Émery Lumumba was born on July 2, 1925, in the village of Onalua in the Katakokombe region of Kasai province, Belgian Congo (now Sankuru province, DRC). Christened Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa at birth, he belonged to the Tetela ethnic group and was the eldest of five children to parents Julienne Wamato Lomendja and François Tolenga Otetshima, a farmer. His original surname, derived from Tetela words meaning “heir of the cursed,” reflected the family’s humble origins, but Lumumba later adopted a name symbolizing resilience and leadership.

Raised in a Catholic household, Lumumba attended a Protestant primary school before transferring to a Catholic missionary school and completing a one-year course at a government post office training school with distinction. Known for his precocious intellect and outspoken nature—he often corrected his teachers—he mastered multiple languages, including Tetela, French, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba. Lumumba drew intellectual nourishment from Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire, as well as French literary giants such as Molière and Victor Hugo. He penned anti-imperialist poetry in his youth, channeling a growing awareness of colonial injustices.

After leaving school, Lumumba worked as a traveling beer salesman in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) and as a postal clerk in Stanleyville (now Kisangani) for over a decade. His personal life was equally dynamic: he married three times, first to Henriette Maletaua and then Hortense Sombosia (both ending in divorce in 1947), before marrying Pauline Opangu in 1951. The couple had five children, including a son, François, born to Pauline Kie in an earlier relationship. These early experiences honed Lumumba’s organizational skills and exposed him to the vast disparities of colonial life, fueling his commitment to social justice.

Lumumba’s political awakening coincided with the post-World War II push for decolonization across Africa. In 1952, he served as a personal assistant to French sociologist Pierre Clément during a study of Stanleyville’s social dynamics. That same year, he co-founded and led a local chapter of the Association des Anciens élèves des pères de Scheut (ADAPÉS). This alumni network doubled as a platform for Congolese intellectuals. By 1955, he had become regional head of the Cercles of Stanleyville, a cultural association, and joined the Liberal Party of Belgium, editing and distributing its literature to advocate for gradual reforms.

A pivotal 1956 study tour in Belgium exposed Lumumba to European political debates, inspiring him to pen an unfinished autobiography (published posthumously in 1962 as Congo, My Country). However, his activism drew colonial scrutiny: in 1957, he was arrested for embezzling $2,500 from the post office, a charge many contemporaries viewed as politically motivated. Convicted and sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment plus a fine, Lumumba served his time while reading voraciously and refining his nationalist ideology.

Released in 1958, Lumumba co-founded the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), a pan-tribal party that championed immediate independence, Africanization of the civil service, state-led economic development, and foreign policy neutrality. Unlike ethnically focused rivals, the MNC appealed to a broad base of urban workers, intellectuals, and rural folk, earning Lumumba widespread popularity. That December, he represented the MNC at the All-African Peoples’ Conference in Accra, Ghana, hosted by Kwame Nkrumah, where his impassioned speeches elevated his profile as a pan-Africanist leader.

Tensions escalated in 1959 amid riots in Stanleyville, where Lumumba was arrested for inciting violence that killed 30 people. Sentenced to six months, his trial overlapped with the historic Brussels Round Table Conference, a negotiation between Congolese leaders and Belgian authorities. Despite imprisonment, the MNC secured a majority in the December 1959 local elections, prompting his release under international pressure. Freed, Lumumba joined the conference, helping secure independence for June 30, 1960. Internal MNC divisions led to a split that year, with Lumumba leading the more centralized MNC-Lumumba faction.

Elections in May 1960 delivered a plurality for the MNC, positioning Lumumba as the frontrunner for prime minister. Amid fractious negotiations, Belgian officials appointed him formateur on June 21 to assemble a national unity government. By June 23, Lumumba had formed a 37-member cabinet drawn from diverse ethnic, class, and ideological backgrounds, including Deputy Prime Minister Antoine Gizenga. Sworn in on June 24 as Prime Minister and Minister of National Defense, Lumumba delivered a defiant independence day speech on June 30, rebuking King Baudouin’s paternalistic address and vowing to build a united, sovereign Congo free from exploitation.

Lumumba’s 10-week tenure was a whirlwind of ambition and adversity. He pushed for rapid Africanization of the administration to replace Belgian officials, proposed amnesties for political prisoners, and nationalized key assets like the Belga news agency. A general amnesty was declared on July 3, though implementation lagged. His most urgent challenge erupted on July 5: a mutiny in the Force Publique (the colonial army) over unpaid wages and racial inequalities. Dismissing Belgian commander Émile Janssens, Lumumba promoted Congolese officers, renamed the force the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC), and appointed Victor Lundula as commander-in-chief and Joseph Mobutu as chief of staff.

The mutiny spiraled into the Congo Crisis, with Belgian paratroopers landing on July 10 to “protect” expatriates, only to back the secession of mineral-rich Katanga province under Moïse Tshombe on July 11. Lumumba protested vehemently, securing UN Security Council Resolution 143 for a Belgian withdrawal and the deployment of the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC). He broke diplomatic ties with Belgium on July 14, appealed to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev for airlifts, and toured the U.S. (July 22–29) and West African states to rally support, signing a secret pact with Nkrumah for an African union.

Declaring a state of emergency on August 9, Lumumba suppressed the South Kasai rebellion but faced accusations of ethnic massacres. An August conference of African leaders in Léopoldville yielded little aid, as Lumumba’s pleas for UN action against Katanga went unheeded.

Fractures within the government boiled over on September 5, 1960, when President Joseph Kasa-Vubu dismissed Lumumba, citing his handling of the crisis and Soviet ties. Lumumba countered by dismissing Kasa-Vubu, but parliament backed him with a vote of confidence. On September 13, lawmakers granted him emergency powers. The next day, Mobutu staged a coup, suspending institutions and confining Lumumba to his residence.

Undeterred, Lumumba fled to Stanleyville on November 27 to rally eastern support. Captured en route on December 1 while crossing the Sankuru River—with his wife and child also seized—he was imprisoned at Thysville military camp alongside allies Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito. Under pressure from Belgian and Katangese interests, Lumumba was transferred to Élisabethville (now Lubumbashi) on January 17, 1961. That night, he was beaten, tortured, and executed by a Katangese firing squad, commanded by Belgian officer Julien Gat, in the presence of Tshombe and others. His body was dismembered and dissolved in sulfuric acid to erase evidence; his death was announced on February 13 as a “popular uprising.”

Lumumba’s murder, widely attributed to a confluence of Belgian, American, and local interests fearing his neutralism, ignited global outrage and deepened the Congo Crisis, paving the way for Mobutu’s decades-long dictatorship. Yet it immortalized him as a symbol of resistance: pan-Africanists hail “Lumumbism,” his doctrine of nationalism, nonalignment, and social progressivism. Statues, streets, and banknotes bear his name across the DRC and Africa; artists like Franco Luambo and Miriam Makeba have eulogized him in song.

In 2002, Belgium formally apologized for its “moral responsibility” in his death, returning a gold tooth—his sole relic—to his family in 2022. Films like Raoul Peck’s Lumumba (2000) and books such as his autobiography keep his fire alive, reminding the world of a leader who dared to dream of a truly free Congo. Though his vision of unity faltered amid Cold War machinations, Lumumba endures as the unyielding voice of decolonization.