A Life at the Center of History

Rodney Glen King was born on April 2, 1965, in Sacramento, California, to Ronald and Odessa King. The second of five children, King grew up in Altadena, a suburb of Pasadena, where his family faced economic hardship. His parents worked as cleaners, and his father, Ronald, struggled with alcoholism, often involving young Rodney and his brothers in his nightly janitorial jobs. Ronald King died in 1984 at age 42 from pneumonia, leaving a profound impact on Rodney’s life. King attended John Muir High School, where he was inspired by his social science teacher, Robert E. Jones, but struggled academically. Functionally literate and placed in special education classes, he dropped out of school in 1984. As a young adult, King worked intermittently in construction and later as a taxi driver, but his life was marked by personal struggles, including issues with alcohol and drugs.

In November 1989, at age 24, King robbed a store in Monterey Park, California, threatening the owner with a tire iron, striking him, and stealing $200. He was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison, serving one year before being paroled. This incident foreshadowed the challenges King would face with the law, which culminated in the event that would define his legacy.

On the night of March 3, 1991, King’s life changed irrevocably. After drinking with friends and watching a basketball game, he was driving on the 210 Freeway in Los Angeles when California Highway Patrol officers Tim and Melanie Singer attempted to pull him over for speeding. Fearing a DUI charge would violate his parole, King led police on an eight-mile high-speed chase, reaching speeds up to 117 mph. When he finally stopped near Hansen Dam Park, LAPD officers, including Sergeant Stacey Koon, Officers Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno, surrounded him. What followed was a brutal beating, captured on video by bystander George Holliday. The footage showed officers striking King over 50 times with batons, kicking him, and using a Taser while he lay on the ground. King suffered a fractured cheekbone, a broken right ankle, multiple facial fractures, and numerous bruises and contusions. The video, broadcast by KTLA and later CNN, sparked global outrage and ignited a national debate on police brutality and racial injustice.

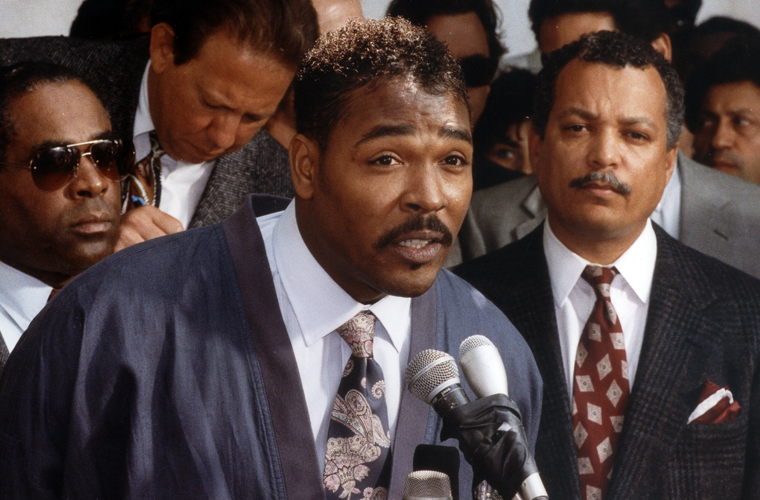

The four officers were charged with assault with a deadly weapon and excessive use of force, with Koon and Powell also facing charges for filing false reports. The trial was moved to Simi Valley in Ventura County to avoid bias, but the predominantly white jury acquitted all four officers on April 29, 1992, except for one assault charge against Powell, which resulted in a hung jury. The verdict shocked the nation and triggered the Los Angeles riots, a six-day uprising fueled by longstanding racial and economic tensions. The riots resulted in 63 deaths, over 2,000 injuries, more than 7,000 fires, and nearly $1 billion in property damage. On the third day of the riots, King made a public plea for peace, delivering his now-iconic words: “People, I just want to say, can we all get along? Can we get along?” Though mocked by some for its simplicity, the phrase became a cultural touchstone, reflecting King’s desire for reconciliation.

In a subsequent federal civil rights trial in 1993, Koon and Powell were convicted of violating King’s civil rights and sentenced to 30 months in prison, while Wind and Briseno were acquitted. King was awarded $3.8 million in a civil suit against the City of Los Angeles for his injuries. The incident led to significant reforms, including the resignation of LAPD Chief Daryl Gates, whose tenure was criticized for institutional racism. The Christopher Commission, established by Mayor Tom Bradley, investigated LAPD practices and recommended changes, leading to a shift toward community policing.

King’s life after the incident was tumultuous. He struggled with addiction, faced multiple arrests for DUI, drug infractions, and domestic violence, and appeared on reality shows like Celebrity Rehab and Sober House. He married twice, to Danetta Lyles and Crystal Waters, and had three daughters: one with Carmen Simpson from his teenage years, and one each from his marriages. In 2010, he became engaged to Cynthia Kelley, a juror in his civil suit against Los Angeles. King spent much of his settlement money on legal fees, cars, and a rap music label, Straight Alta-Pazz, which failed. Despite his struggles, he expressed forgiveness for the officers who beat him, stating in a 2012 CNN interview, “Yes, I have forgiven them because I have been forgiven so many times.” He also believed his ordeal contributed to social change, telling The Los Angeles Times that it “made the world a better place” and paved the way for figures like Barack Obama.

King found solace in fishing and poetry, and was known for his kindness and generosity within his community. In April 2012, he published a memoir, The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption, expressing pride in sharing his story despite his limited literacy. Tragically, on June 17, 2012, King was found dead by his fiancée, Cynthia Kelley, at the bottom of his swimming pool in Rialto, California. An autopsy determined his death was an accidental drowning, with alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana in his system as contributing factors. He was 47.

King’s legacy endures through his daughter Lora King’s work with the Rodney King Foundation, which promotes community-police relations and social justice. While King never sought to be a symbol, his beating and the subsequent riots forced America to confront issues of police brutality and systemic racism. His story remains a powerful reminder of the ongoing struggle for justice and equality, encapsulated in his heartfelt plea for unity.