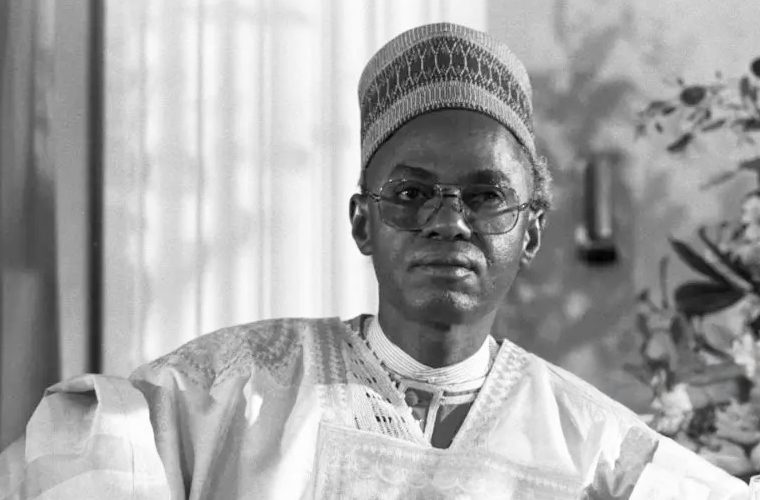

Nigeria’s First Executive President

Shehu Usman Aliyu Shagari (February 25, 1925 – December 28, 2018) was a Nigerian statesman, educator, and politician who became the country’s first democratically elected executive president, serving from 1979 to 1983 during the Second Republic. A devout Sunni Muslim from the Fulani ethnic group, Shagari was known for his mild-mannered demeanor, integrity, and commitment to national unity amid Nigeria’s ethnic and regional diversity. His tenure, marked by ambitious development projects fueled by oil revenues, was ultimately undermined by economic downturns, corruption scandals, and political instability, leading to his ouster in a military coup. Despite these challenges, Shagari is remembered as a bridge-builder in Nigerian politics, embodying humility and diligence in public service.

Born in the rural village of Shagari in what is now Sokoto State, northern Nigeria, Shagari hailed from a prominent Fulani family. The village itself was founded by his great-grandfather, Ahmadu Rufa’i, in the early 19th century. As the eleventh child in a polygamous household, Shagari grew up in modest circumstances. His father, Aliyu Shagari, served as the village head (Magajin Shagari), transitioning from farming, trading, and herding to traditional leadership. Aliyu passed away when Shehu was just five years old, leaving the young boy under the care of his elder brother Bello, who briefly succeeded as village head.

Shagari’s early education reflected the blend of Islamic and Western influences common in northern Nigeria. He began with Quranic studies before attending Yabo Elementary School from 1931 to 1935. He continued at Sokoto Middle School (1936–1940) and then Barewa College, a prestigious secondary institution in Zaria (1941–1944), where he honed his intellectual and leadership skills. From 1944 to 1952, Shagari trained as a teacher at the Teachers Training College in Zaria, Kaduna State. Upon graduation, he taught in Sokoto Province from 1953 to 1958 and served on the Federal Scholarship Board from 1954 to 1958, advocating for accessible education in underserved areas.

Shagari’s political awakening came during his teaching years. In 1945, at age 20, he founded the Youth Social Circle in Sokoto to foster anti-colonial activism, serving as its secretary until it merged into the Northern People’s Congress (NPC) in 1948—a party that championed northern interests. His outspokenness led to repercussions; in 1948, after attending a pivotal meeting with nationalist leader Nnamdi Azikiwe to protest the Richards Constitution, colonial authorities withheld his salary as punishment. Undeterred, Shagari penned anti-colonial writings, including a Hausa pamphlet titled Anti-Colonialist and an article for Azikiwe’s West African Pilot newspaper.

Elected to the Federal House of Representatives for Sokoto West in 1954, Shagari rose swiftly. He served as parliamentary secretary to Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (1958–1959) and held ministerial portfolios under Nigeria’s First Republic (1960–1966): Commerce and Industries (1959), Economic Development (1959–1960), where he oversaw the 1962–1968 national development plan and established the Niger Delta Development Board; Pensions (1960–1962), advancing the “Nigerianization” of the civil service; Internal Affairs (1962–1965); and Works (1965–1966), during which he commissioned major infrastructure like the Eko Bridge in Lagos and the Second Niger Bridge.

The 1966 military coup disrupted civilian rule, prompting Shagari’s temporary withdrawal from national politics. He focused on local education initiatives in Sokoto, serving as executive secretary of the Sokoto Province Education Development Fund in 1967 and building schools as commissioner for establishments in the North-Western State. Re-entering federal service under General Yakubu Gowon, he became federal commissioner for Economic Development, Rehabilitation, and Reconstruction (1970–1971), aiding post-Civil War reconciliation in the southeast. As finance commissioner (1971–1975), he introduced the naira currency, represented Nigeria at the World Bank and IMF, and established the Nigeria Trust Fund at the African Development Bank with an initial $100 million contribution. Shagari also mediated international tensions, such as averting the Uganda–Tanzania War by brokering talks between Julius Nyerere and Idi Amin.

A founding member of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) in 1978, Shagari emerged as its presidential candidate in the 1979 elections following the military regime’s transition to democracy under Olusegun Obasanjo. Narrowly defeating Chief Obafemi Awolowo, he secured victory with strong northern support and alliances with southern minorities.

Presidency (1979–1983)

Inaugurated on October 1, 1979, with Alex Ekwueme as vice president, Shagari’s administration capitalized on the oil boom to drive modernization. Key initiatives included the “Green Revolution” in agriculture, which distributed seeds and fertilizers to farmers and commissioned dams like Bakolori, Kafin Zaki, and the South Chad Irrigation Scheme. Industrial efforts saw the completion of the Kaduna Refinery (1980), the launch of the Ajaokuta Steel Mill, and the establishment of the Aluminium Smelter Company. Housing programs targeted 200,000 units annually, completing 32,000 by mid-1983, while transportation infrastructure expanded with highways (e.g., Badagry-Sokoto Expressway) and upgraded ports in Sapele and Port Harcourt.

Education received a major boost: secondary schools proliferated, a 1981 mass literacy campaign targeted adults, and the 6-3-3-3-5 education system was introduced in 1982. New universities of technology opened in states like Bauchi, Benue, and Imo, alongside polytechnics and the National Open University. Shagari promoted inclusivity by appointing women like Ebun Oyagbola as Minister of National Planning and youth like Pat Utomi as economic adviser. Military modernization included acquisitions of Alpha jets, C-130 Hercules aircraft, and the frigate NNS Aradu.

Foreign policy emphasized pan-Africanism: Shagari supported anti-apartheid struggles, pledged $15 million for Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, and bolstered ECOWAS. However, challenges mounted. The global oil price crash from 1981 triggered economic woes, prompting austerity measures like import curbs and IMF consultations, but these yielded limited success. Corruption and ethnic tensions simmered, exemplified by the 1980 Kano riots (over 4,000 deaths) and a 1983 deportation of two million undocumented immigrants, mostly Ghanaians. Amid 1983 election fraud allegations, Shagari launched anti-corruption drives like the Ethical Revolution, but his second-term cabinet retained only seven of 45 ministers.

Overthrow and Later Life

Re-elected in a contentious 1983 vote, Shagari’s government collapsed on December 31, 1983, in a bloodless coup led by Major General Muhammadu Buhari, who cited corruption and mismanagement. Shagari was arrested and detained until 1986, when he was cleared of personal wrongdoing and released, though banned from politics for life. Retiring to Sokoto, he authored several books, including his autobiography, Beckoned to Serve (2001), a poetry collection, Wakar Najeriya (“Song of Nigeria”), and works on leadership like Uthman Dan Fodio: The Theory and Practice of His Leadership.

In his later years, Shagari became an elder statesman, advising on national reconciliation. On his 90th birthday in 2015, he hosted five former presidents, including Goodluck Jonathan. Even Buhari, in his ouster, eulogized him as a “patriot who served Nigeria with humility, integrity, and diligence.”

Death and Legacy

Shagari died on December 28, 2018, at age 93 from a brief illness at the National Hospital in Abuja. He was buried in his hometown of Shagari, drawing dignitaries from across Nigeria. His legacy endures as a symbol of democratic transition and nation-building, though critiques persist over unfulfilled economic promises and graft under his watch. As Nigeria marked its centennial in 2025, reflections highlighted its role in laying the foundations for federalism and infrastructure that still shape the nation today. Shagari’s life, from village teacher to presidential pioneer, exemplifies the complexities of leading Africa’s most populous country through prosperity and peril.