Among the most potent weapons in the rhetorical arsenal of abolitionism was the charge that slaves were physically mutilated by branding, “like sheep or cattle”. This was, according to author Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846), an ignominious “mark of property,” which served to debase enslaved people and split them off from the humanity of the master class. In recent decades, however, historians have taken little notice of branding, either with regard to its prevalence, purposes, or impact on bond people.

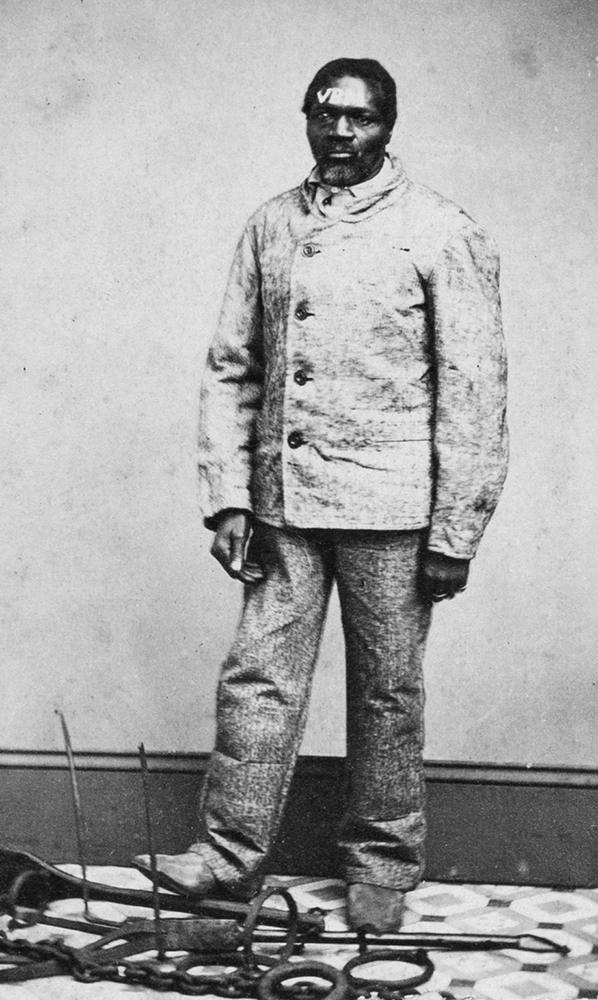

In the early twentieth century, even conservative scholars such as Ulrich Phillips (1877–1934) and Charles Sydnor (b. 1898) admitted that “negroes were sometimes branded on the chest or face,” though their research in newspapers and plantation and legal records argued that, by the antebellum period, such treatment was reserved for those considered as slave criminals—runaways, thieves, and recalcitrants (Sydnor 1933, p. 89). Under English law, branding was applied most commonly as punishment for theft or flight by indentured servants and apprentices from the Elizabethan period onward, and colonial and state governments in the South carried the practice down to secession on whites and blacks alike.

In South Carolina, for example, branding robbers in the hand, or marking fugitives with the letter R (for runaway) went hand in hand in the legal code from 1690 with such other barbarities as slitting noses and carving off ears. By the early nineteenth century, however, branding as a punishment for crime largely fell into disuse, not least because of the widespread adoption of whipping as an educative mechanism of social discipline. For historians searching out the origins of paternalist slave management strategies, this shift seems crucial.

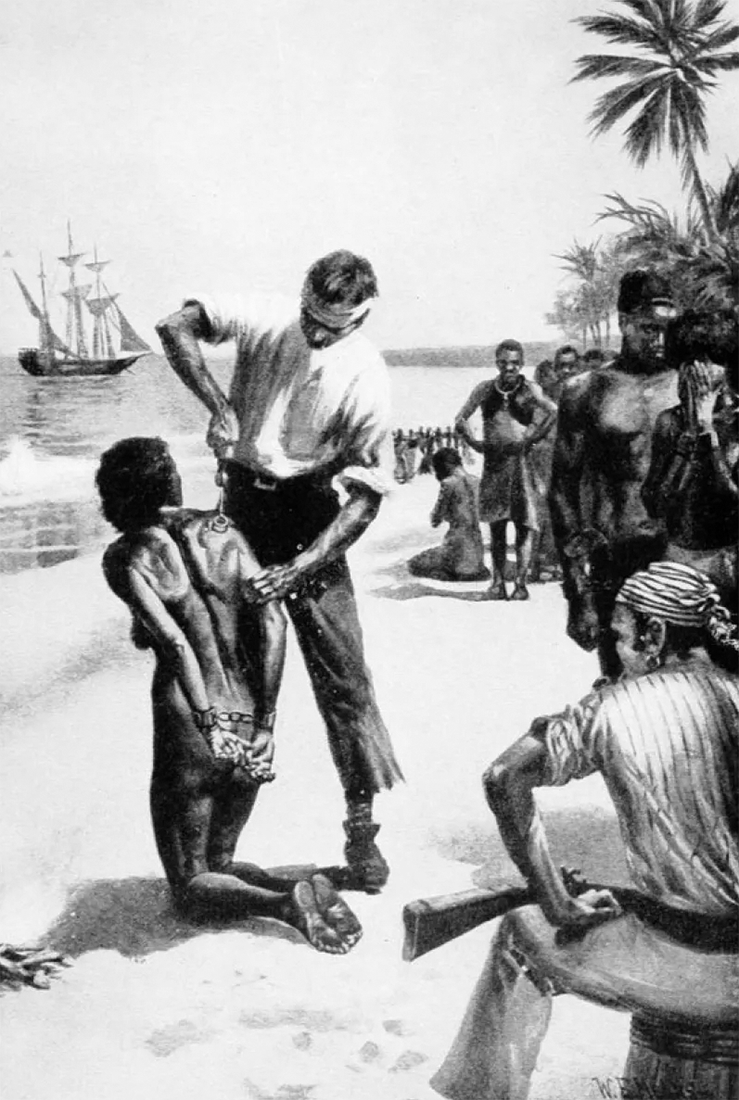

Originally, however, branding seems to have served a commercial purpose on the African coast. It marked blacks as the living property of another and conferred upon them an ineradicable identity with their owner. In 1744, geographer Joseph Randal reported that merchants engaged in the Guinea slave trade marked their purchases with hot irons to distinguish them from one another prior to making the Middle Passage. Because the human chattels of various traders were lumped together in coastal pens and on shipboard, branding allowed for easy sorting as well as commodification. Two generations later, Samuel Hopkins (1721–1803) described the practice as universal. “All that is passed as fit for sale,” he noted “are branded with a hot iron in some part of their body, with the buyer’s mark”

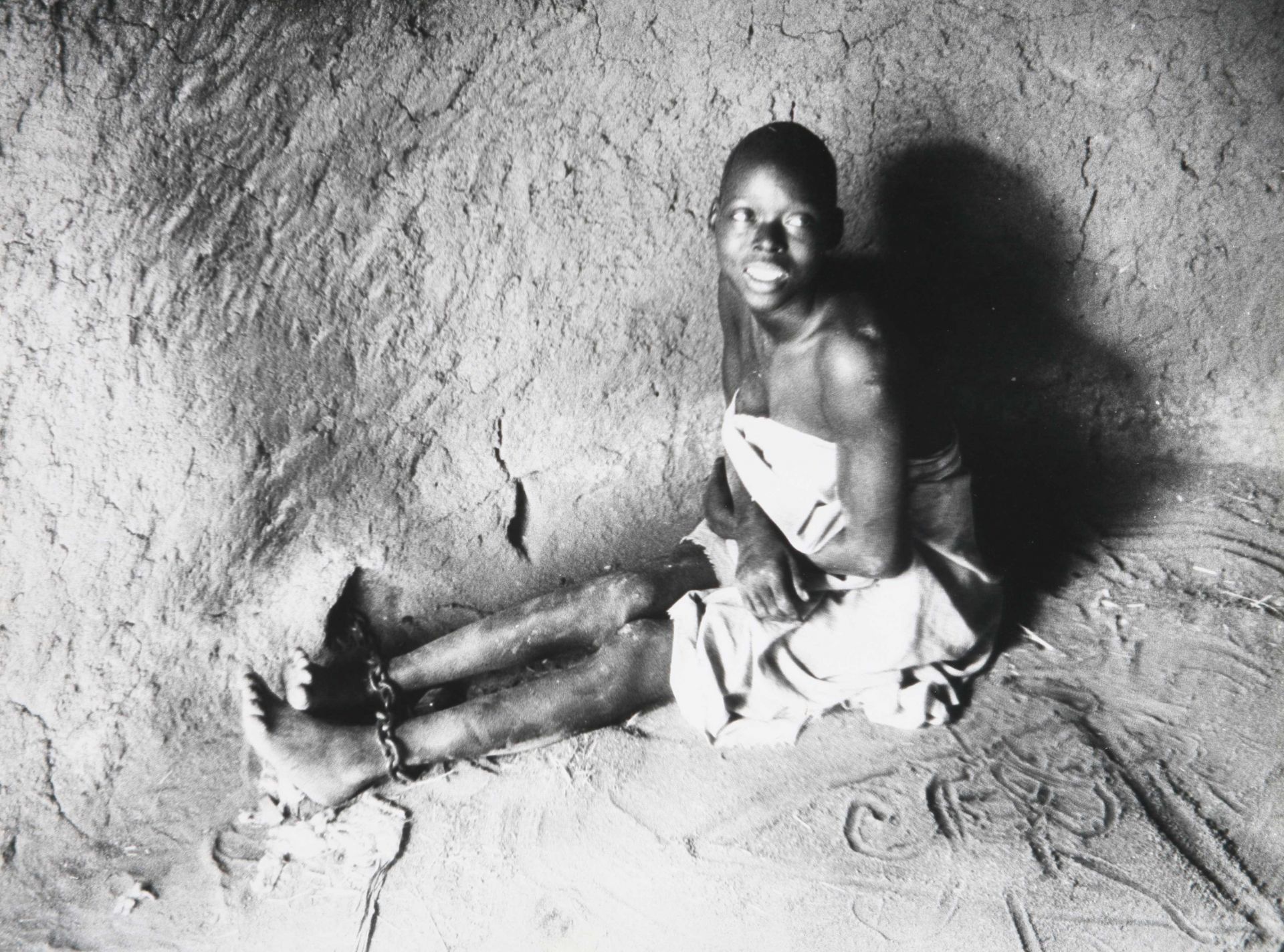

In British colonial slave regimes, branding served both to identify bondmen and women with particular owners and to differentiate them from free blacks. “I take not the cruel, though common precautions to prevent their running away,” announced one Jamaican master, “by branding their flesh with the letters of my name, or the marks of my plantations”. Such individual choices, however, made the task of social control more difficult. Where a wandering black was taken up bearing no brand mark, establishing his social identity could make abundant trouble for authorities.

By the early nineteenth century, however, much of the social uncertainty of individual black identity, which gave branding its raison d’être, had fallen away, as the social networks of southern communities increased in range and complexity. Imprinting ownership of black bodies became an impediment to ready sale at market prices. Physical mutilation now served only as a marker of diminished commercial value. Most masters learned to resist the temptation to mark troublemaking slaves as such before carrying them to the auction block. Caveat emptor was warning enough, and it paid better, besides.

Even as the practice of branding subsided, however, it grew in cultural and political importance across the antebellum era. Coupled with a growing cultural fascination with sentiment and the senses, and a new ideology of possessive individualism, branding came to embody all that was most appalling to romantic minds. John Riland recollected seeing “a newly purchased set of Negroes of both sexes, and of various ages” branded during his boyhood in Jamaica. “One of the parties, a boy of fourteen, shrieked and twisted himself in such a fearful way, and, at the same time, looked so piteously at me, that I began to feel frightened and sick, and left the place in haste”.

Increasingly antislavery orators learned to win their point—and pack in audiences—by parading “the gashes of whips and branding”. Both fascinated and disgusted, bourgeois crowds with few apparent ties to the abolitionist cause found commitment through the generation of such feelings of sympathy and revulsion. Graphic descriptions of “branding the flesh with red-hot irons” only redoubled their power by mingling high-minded reform with sadomasochistic prurience. Branding and slavery here became part of the Victorian encounter with pornography, and middle-class whites rallied to its eradication, even as they were titillated by the “indelible ignominy” of it all. That southern masters and proslavery ideologues denied having anything to do with branding—that they deplored the few miscreants who still marked their bond people as chattel—was quite beside the point.

American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, authored by abolitionist Theodore Weld (1803–1895), offered only three references to branding. But in pointing up what masters had the power to do, such abolitionist propaganda hinted at the deepest lusts for domination and debasement within every heart. Originally interpreted as a legal and commercial measure, branding gained its greatest strength as a moral discourse of antislavery activism.