Mental illness has a dark history in the United States—one too often clouded by stigma and ignorance. Now a UT researcher is uncovering the records of tens of thousands of African-American psychiatric patients so that, more than 100 years later, their forgotten stories can finally be told.

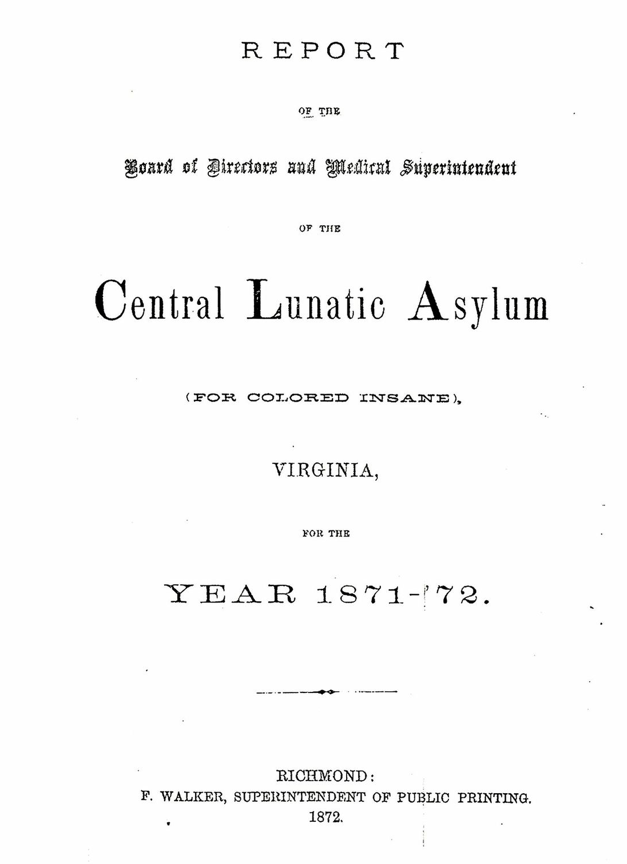

UT professor King Davis is leading a project to digitize and preserve records from the archive of the world’s first mental institution for African Americans. The Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane was founded in Petersburg, Va., in 1870 to serve African-Americans across the state. The hospital was renamed Central State Hospital, and it was the only mental institution for African-American patients in Virginia until it was integrated in 1970.

King, who directs UT’s Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis, got involved in the project when a colleague told him that a century’s worth of records from the hospital was about to be destroyed to free up storage space. He immediately knew he had a wealth of information on his hands.

“Every African-American person in the state who had a psychiatric illness ended up in this hospital,” Davis says. “So, what we have are the records of everybody. Whether they were a pauper or a dignitary, they were in this hospital.”

“Every African-American person in the state who had a psychiatric illness ended up in this hospital,” Davis says. “So, what we have are the records of everybody. Whether they were a pauper or a dignitary, they were in this hospital.”

The archive contains more than 800,000 documents, including photographs, annual reports, newspaper clippings, and half a million index cards that document every patient.

Annual reports from 1870-1970 document how many patients died, diagnoses of patients who were admitted, and involuntary commitment rates. They also note patients’ length of stay, which patients died and how, and more.

For Davis, whose research focuses on mental health policy, the data is a treasure trove.

“Most of the original African-American hospitals have been closed for years,” Davis says. “No one kept their records. This is the most complete set of records on African Americans and mental health in place in the world.”

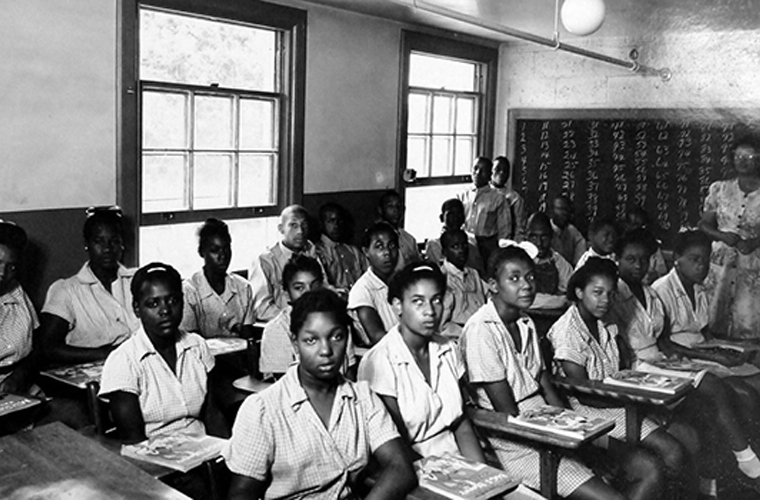

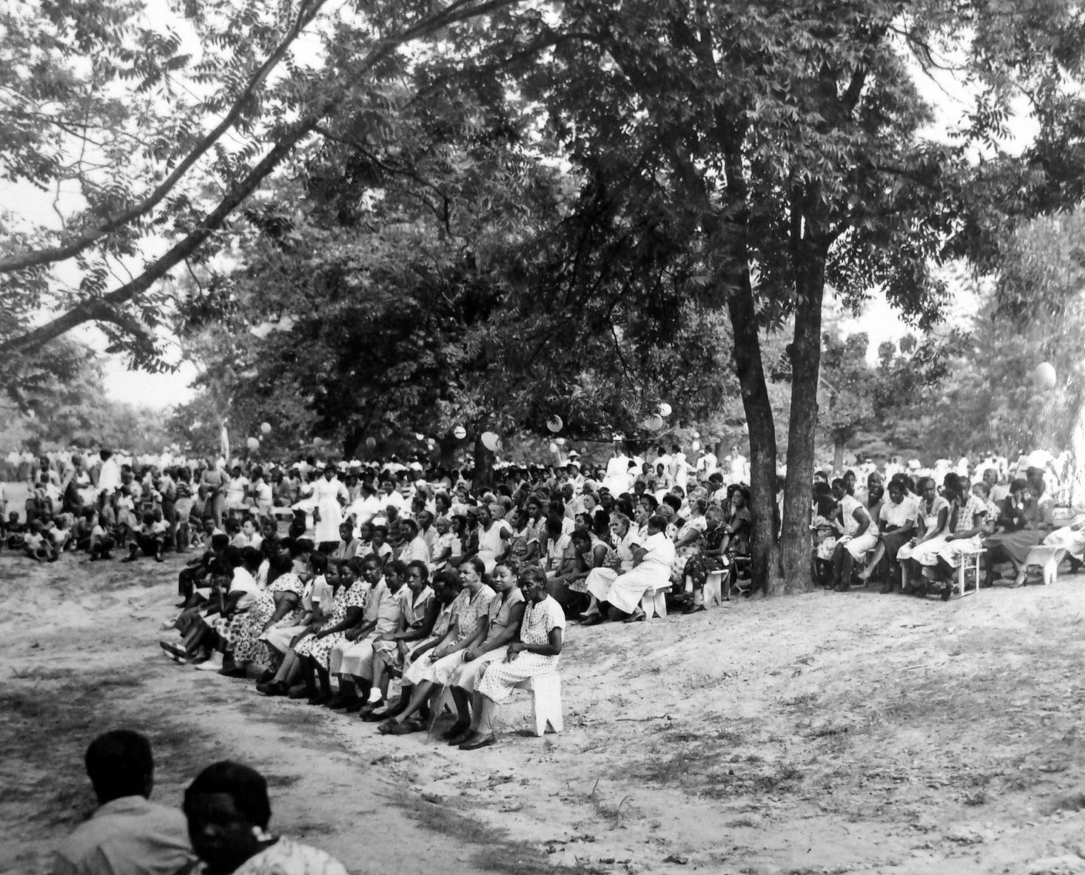

The records also offer a glimpse into day-to-day life at the hospital. Photographs show patients attending musical performances on the hospital grounds and nurses in training. They also show patients in the garden, tilling the rows.

“It was hard at times to distinguish between whether they were staff or whether they were patients. Was that work therapeutic, or were they taking on staff responsibilities to keep costs down?” Davis wonders.

Records show that patients performed janitorial work at nearby hospitals, which Davis says raises troubling questions today. The records also show that African Americans were often admitted to the hospital simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“They were admitted because they sassed a police officer, they were admitted because they didn’t get along with an employer, they were admitted because they were on the wrong street,” Davis says. “The first person admitted was a woman named Edith Smith, and she was admitted because she was old and had no place to go.”

While mental health care has improved dramatically in the intervening century, Davis says that African Americans are still diagnosed with severe mental illness more than any other demographic group.

“That was true in 1870, 1970, and 2010,” he says, “even to the point that the diagnosis is greater than one could accommodate statistically, so you know that probably it’s a false diagnosis.”

Now Davis is working to put all the records online so students and researchers around the globe can learn from them. Digitizing hundreds of thousands of artifacts is a daunting task, so King has teamed up with two digital experts at UT’s School of Information, Unmil Karadkar, and Patricia Galloway, along with graduate student Lorraine Dong, who cataloged the collection.

The team must balance access with privacy concerns. Karadkar is working with his students in the I-School to explore ways of assigning tiered access in the database. For example, a family member might be able to access family records, while an outside researcher would be able to see records such as the annual reports and photographs in the system.

The team must balance access with privacy concerns. Karadkar is working with his students in the I-School to explore ways of assigning tiered access in the database. For example, a family member might be able to access family records, while an outside researcher would be able to see records such as the annual reports and photographs in the system.

The searchable database could open new areas of interdisciplinary research. Data gleaned from these documents could be used to help health administrators shape policy for mental health patients to improve diagnosis and treatments. Armchair genealogists looking to learn about their ancestry could uncover new information, too.

Unfortunately, the project is mostly at a standstill right now. While funding from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors and Samsung has been helpful, other expected funding didn’t pan out. In the meantime, King feels the clock ticking.

“We ran out of money, and without that, we are worried about a lot of our materials, which are kept on hard drives in my closet and in an air-conditioned space at the I-School,” Davis says. “External hard drives fail about 50 percent of the time. We are really concerned that we need to get this on a server or a cloud so that the 150,000 [records] we’ve already scanned don’t disappear.”

Photos from top: A nurses’ training class at Central State Hospital; patients on an outing; the hospital’s first annual report, for 1871-72; and a gathering of patients listening to a musical performance.