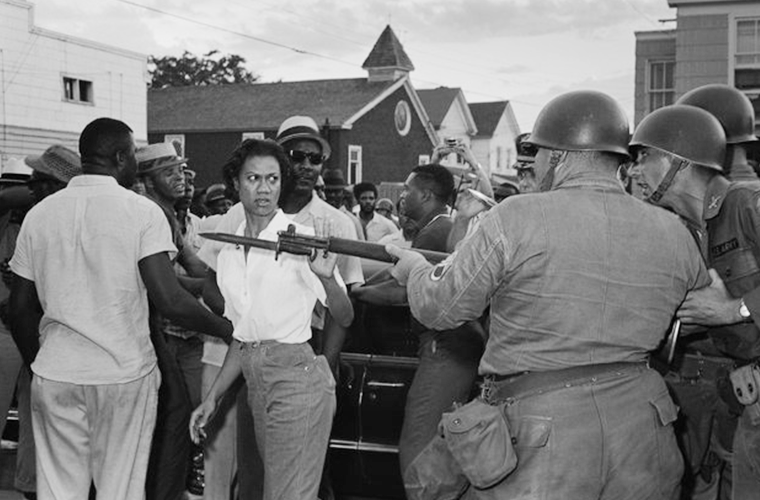

She speaks to many of us — a black woman, dressed in a buttoned shirt and jeans, pushing aside a National Guardsman’s bayonet as though to say ‘I ain’t got time for this shit.’ But who was she? Her name is Gloria Richardson and at the time of the photo, she was a 41-year-old housewife-turned-activist fighting for civil rights in her town of Cambridge, Maryland.

Born into an affluent black family Richardson attended Howard University and graduated in 1942 with a degree in sociology. Despite her education, she had a difficult time finding work due to hiring discrimination and eventually settled into life as a mother and housewife. Richardson’s situation was not uncommon. In 1961 black unemployment in Cambridge was 40% — 4 times that of whites — in large part because two large factories in town agreed to hire whites only in exchange for the workers not unionizing.

“In Cambridge, all lunch counters, cafes, churches and entertainment venues were either separated with white and Black sections or had race-specific days. Schools were segregated and Black children received half the funding of white children. Residents of the Second Ward were forced to travel two hours by car to Baltimore if they wanted to visit a hospital because the local Cambridge hospital would not admit them.”

Richardson had learned early that her affluence could not protect her from cruel discrimination, as she told the BBC in a 2015 interview.

“My uncle got typhoid fever and died and he could not go to the hospital. My father 20 years later was in the same position as a heart attack. He could not get any help from the heart specialist in Cambridge. I think that both my uncle and my father, had there been different kinds of medical treatment available, would have been alive. We were supposed to be one of the top families that white folks approved of and even with that we did not have those services available.”

When the civil rights movement began to spread across the country Richardson and her high-school-aged daughter Donna got involved. Donna joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and, in 1962, Richardson helped create its first non-student affiliate, the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee. Richardson was asked to lead the group due to her education and speaking ability.

“The men in Cambridge asked me to be the spokesperson and I considered that I guess like soldiers in the army, this is something you’re supposed to do.”

In spring 1963 the CNAC drew up a list of demands including the desegregation of jobs, schools, and housing as a path to socioeconomic parity. This was considered radical at the time because most civil rights campaigns were focused on voting rights. Having already received that right, blacks in Cambridge focused on dismantling the socioeconomic racism of their community. The Cambridge movement, as it was called, was the first wide-scale push for civil rights outside of the Deep South.

“We drew up a survey. Out of that, they wanted better housing, they wanted the schools desegregated they wanted access to better jobs and they wanted the hospital desegregated… I guess in retrospect we were more radical and certainly, I think they thought we were crazy.”

The city flat-out refused to negotiate with Richardson and the CNAC, leading to months of rallies and sit-ins, but the protests turned violent when white cops beat a group of black teens at Cambridge’s local theater. Black citizens violently clashed with whites, in part because Richardson did not embrace a pacifist philosophy.

“My position on violence and non-violence; I always thought that if they come to where you live then defend yourself. I always believed if they came and attacked you you had a right to respond.”

“It was actually like civil war, and I say civil war because the blacks and whites were fighting hand to hand. The whites were tough, the blacks were tough, and people were just at everybody’s throats. And I guess all of that pent-up fury came out… It was like living in a war zone. The shooting at night, it would be at least an hour or two of shooting. When the sun broke through at 5 or 6 a.m. it was like clouds of smoke from gunfire.”

In June 1963, after weeks of fighting Governor J. Millard Tawes imposed martial law on Cambridge and the town’s mayor called in 800 National Guardsmen. An 8 o’clock curfew was imposed. The Cambridge movement began to draw national attention and it was at this time that a press photographer took the iconic image of Richardson.

“This soldier proceeded to put his bayonet in a position like he was gonna charge me and that’s when I — I don’t remember, I mean the picture says I did — but I don’t remember making up my mind ‘Oh, he’s gonna stab me and I’m going to push this bayonet, especially because I don’t like sharp things.’ But in any event, I pushed the bayonet away.”

Despite mounting pressure, an agreement with the city was hard to come by. A treaty meeting the CNAC’s demands was drawn up, but eventually dissolved via referendum according to LiberationSchool.org;

“On July 23, the Treaty of Cambridge was signed between city officials, civil rights organizations, and the Justice Department. The agreement called for immediate desegregation of schools and hospitals, the construction of low-rent public housing, the Maryland Department of Employment Security and the Post Office hiring Black workers, the appointment of a human relations commission, and an amendment to the city charter to desegregate public spaces. This Treaty, a victory won through the organization and militant fight-back of Second Ward residents, unraveled when segregationist politicians and businessmen forced it to a referendum. Richardson took the controversial

“The legacy of Cambridge is that people found out that they could fight city hall and win, that they may have to give up almost their lives to do it, and that things will change if you fight hard enough for them.”step of calling for a boycott of the referendum—even though the civil rights side may have been able to win—arguing that, “A first-class citizen does not plead to the white power structure to give him something that the whites have no power to give or take away. Human rights are human rights, not white rights.” She further emphasized that the Treaty’s focus on segregation obscured the demands for housing and economic equality. Richardson’s move alienated many of the larger established civil rights groups but made her a pole of attraction to the next generation of young Black militants developing in the direction of Black Power. Cambridge, Maryland further polarized, causing the government to take aggressive steps to improve conditions and prevent full-scale “civil war,” which Richardson warned could come.”

“The legacy of Cambridge is that people found out that they could fight city hall and win, that they may have to give up almost their lives to do it and that things will change if you fight hard enough for them.”