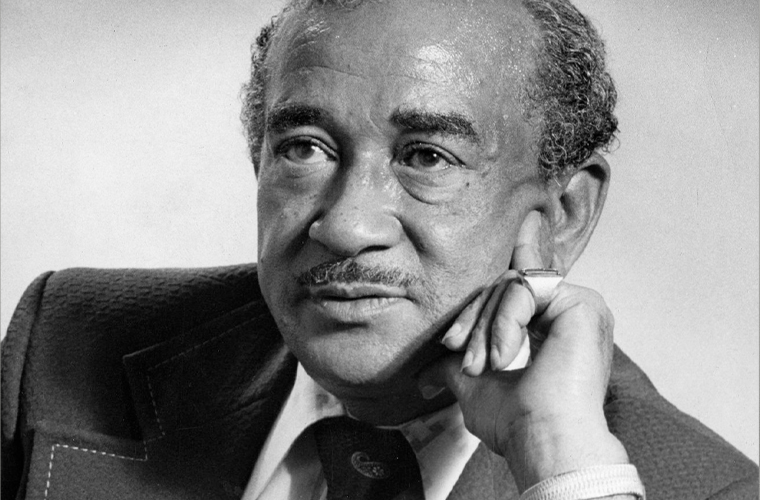

Cecil B. Moore was a defense attorney and civil rights activist in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Through pickets and other protests, he helped to integrate construction sites, post office jobs, and schools. He headed the Philadelphia chapter of the NAACP from 1963 to ’67, though his tenure was marked by conflict with those who disagreed with his bold approach. The outspoken Moore was often at odds with anyone he believed to be too moderate and accepting of incremental progress, making him a controversial figure in civil rights.

Cecil Bassett Moore was born in Dryfork Hollow, West Virginia, on April 2, 1915, to a doctor father, and teacher mother. Growing up in West Virginia, Moore’s family was targeted by the Ku Klux Klan at one point because they thought his father, a light-skinned Black man, was actually a white man living with a Black woman. Moore graduated from Bluefield State College, a historically Black college, though he took classes at several other schools. He worked as a traveling insurance salesman before signing up for the Marine Corps.

In 1942, Moore joined the Marine Corps, where he was known for his willingness to speak out against discrimination. During World War II, Moore fought in the Pacific theater. In 1947, he was transferred to Fort Mifflin, near Philadelphia. In 1949, while still in the Marines, Moore began attending night classes at Temple Law School. He also worked as a liquor wholesaler to pay for his classes.

Though President Harry Truman had ordered integration within the armed services, Moore still encountered discriminatory treatment. He opted to leave the service and in 1951 received an honorable discharge at the rank of sergeant. Moore’s military experiences contributed to his desire for equal rights. He once said, “After nine years in the Marine Corps, I don’t intend to take another order from any son of a bitch that walks.” After graduating in 1953, Moore became an in-demand defense attorney. He often represented poor clients for free or for reduced fees.

Moore was a driven civil rights activist in Philadelphia. He held voter registration drives and encouraged Black people to vote. He arranged pickets to integrate construction sites. He also held protests at workplaces — such as Greyhound and the U.S. Postal Service — that exhibited bias toward Black employees. Thanks to Moore’s actions, in 1964 Philadelphia stopped using blackface in the city’s Mummers (New Year’s Day) parade. In 1965, Moore used pickets to push for the integration of Girard College, a Philadelphia boarding school that only admitted white boys. The school was desegregated in 1968.

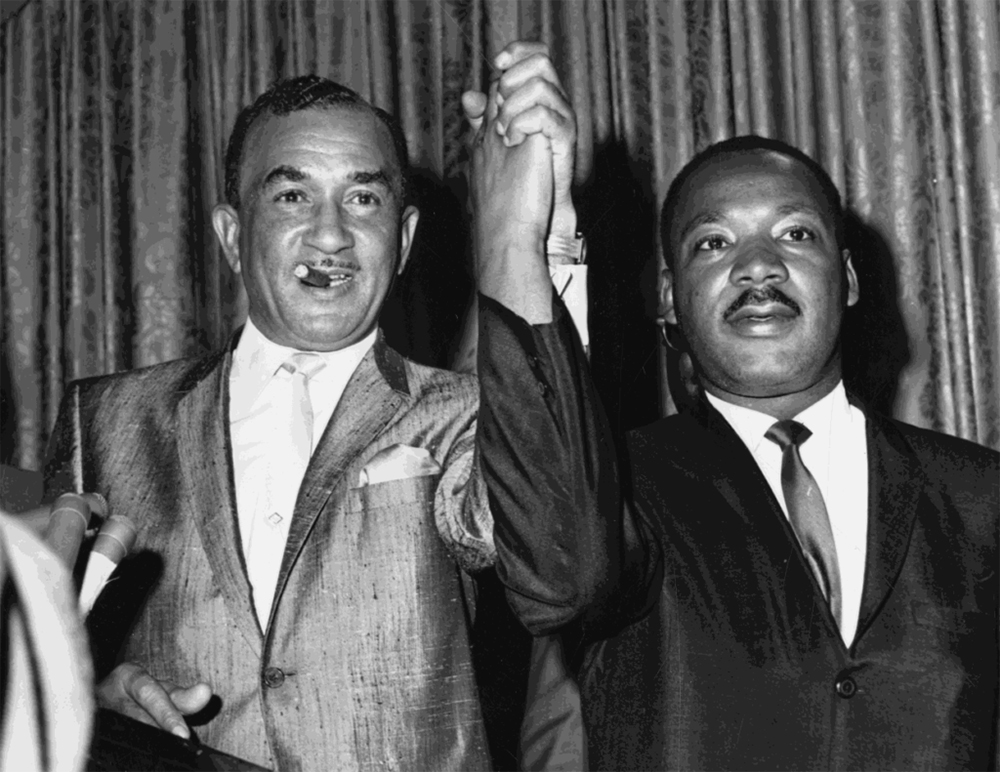

Yet Moore could be a divisive figure. He reportedly objected when Martin Luther King Jr. came to Philadelphia and didn’t coordinate with him. Moore also disdained many middle-class Black professionals in Philadelphia, whom he viewed as willing to content themselves with piecemeal advances when it came to civil rights.

Though Moore was described as militant and even fanatical, he was an effective leader who was able to forge a connection with working-class Black people. He clearly shared his philosophy in a quote from 1974: “I said to hell with the club, let’s fight the damn system. I don’t want no more than the white man got, but I won’t take no less.”

Moore brought his views on the best way to fight for civil rights to the NAACP. He was elected president of the Philadelphia branch of the organization in 1962. In his inaugural speech in January of the next year, Moore declared, “We are serving notice that no longer will the plantation system of white men appointing our leaders exist in Philadelphia.”

The NAACP found it difficult to work with Moore. He tripled membership in his chapter to 25,000 but also criticized national leaders for being weak and alienated churches, the Black middle class, and white liberals in the organization. Moore baldly stated, “I run a grass-roots group, not a cocktail-party, tea-sipping, fashion-show-attending group of exhibitionists.”

In 1964, aggrieved members of his chapter accused Moore of the improper use of funds. He managed to clear his name of financial malfeasance and win re-election as chapter president in 1965. Yet conflicts with NAACP leaders remained. In 1966, the national organization decided to divide the Philadelphia NAACP into smaller branches. This reduced Moore to heading a North Philadelphia chapter until he left his leadership role in 1967.

Moore made unsuccessful runs for Congress in 1958 and became mayor of Philadelphia in 1967. He was elected to Philadelphia’s City Council in 1975 and served from 1976 to ’79.

On February 13, 1979, a 63-year-old Moore passed away in Philadelphia after suffering a heart attack.

In 1987, the city of Philadelphia renamed Columbia Avenue Cecil B. Moore Avenue in Moore’s honor. A local public transportation stop was named after Moore in 1995. The city is also home to a public library bearing Moore’s name.

Moore married Theresa Wyche Lee Moore in 1946. They had three daughters. Theresa Wyche Lee Moore passed away in 1970. In 1972, Moore wed Helen Golden Boyer.