Nearly 450 enslaved African-Americans were jammed into stalls at a horse track outside Savannah, to be sold to the highest bidder as part of the nation’s largest slave auction. It lasted two days. People in Atlanta and Savannah will gather today and Friday to memorialize “The Weeping Time.” Here, we’re reposting an AJC story about the 1859 sale. Details about Friday’s Atlanta commemoration are at the end of this story.

In the mid-1800s, brothers Pierce and John Butler had what was then a fortune, about $700,000, $20 million in today’s dollars. They loved the high life it afforded. For a costume ball, John Butler had a steel suit of armor made just for the occasion. Never wore it again. Pierce Butler was addicted to gambling.

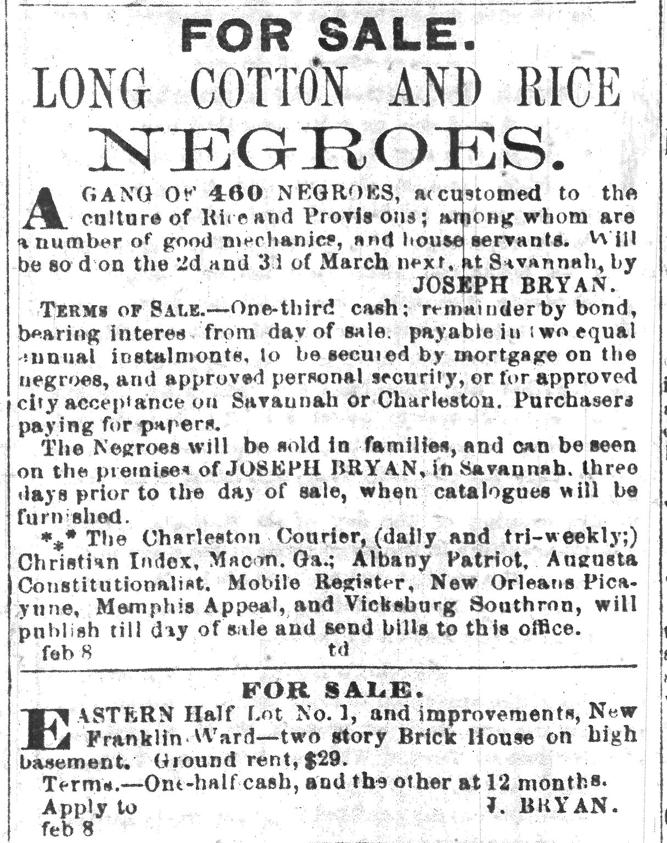

Original newspaper advertisement for “The Weeping Time” sale of slaves owned by Pierce M. Butler.

Original newspaper advertisement for “The Weeping Time” sale of slaves owned by Pierce M. Butler.

Facing bankruptcy after years of lavish spending, Pierce Butler, owner of plantations on Butler and St. Simons islands, cashed in his remaining assets. Over two rainy days in March 1859, and with great fanfare, his estate held what amounted to a liquidation sale. Here is part of the lot he sold:

Fielding, 21; cotton,

prime, young man Abel, 19; cotton,

prime young man Sold for $1,295 each

Anson, 49; rice—rupture, one-eyed Violet, 55, rice hand Sold for $250 each

Dorcas, 17; cotton, prime woman

Joe, 3 months Sold for $1,200 each

In all, Pierce M. Butler sold 436 human beings. They’d made his family a fortune, one even trustee of his estate couldn’t keep him and his brother from squandering.

“The Weeping Time,” as it came to be known, was the largest single sale of slaves in the nation’s history.

Over the past several months, as Georgia debated the legacy of the Confederacy — which landmarks should stay, which should go, which should be revered, which should be reviled — the significance of slavery often went unmentioned. Typically the South has honored the legacy of the Confederate and ignored the legacy of the enslaved. As a consequence, “the Weeping Time” has largely been forgotten.

The Butler family built its fortune off the labor of hundreds of slaves who grew cotton and rice on the family’s Sea Island plantations. It was this group of men, women, and children who were kept in holding pens at the Ten Broeck Race Course outside Savannah for a week to allow potential buyers to inspect them like cattle before bidding on them.

The eyewitness accounts of the sale are searing: Buyers pulled the slaves’ mouths open to looking at their teeth, made them perform rudimentary exercises to assess agility, and in the case of the women, asked if they were still able to breed.

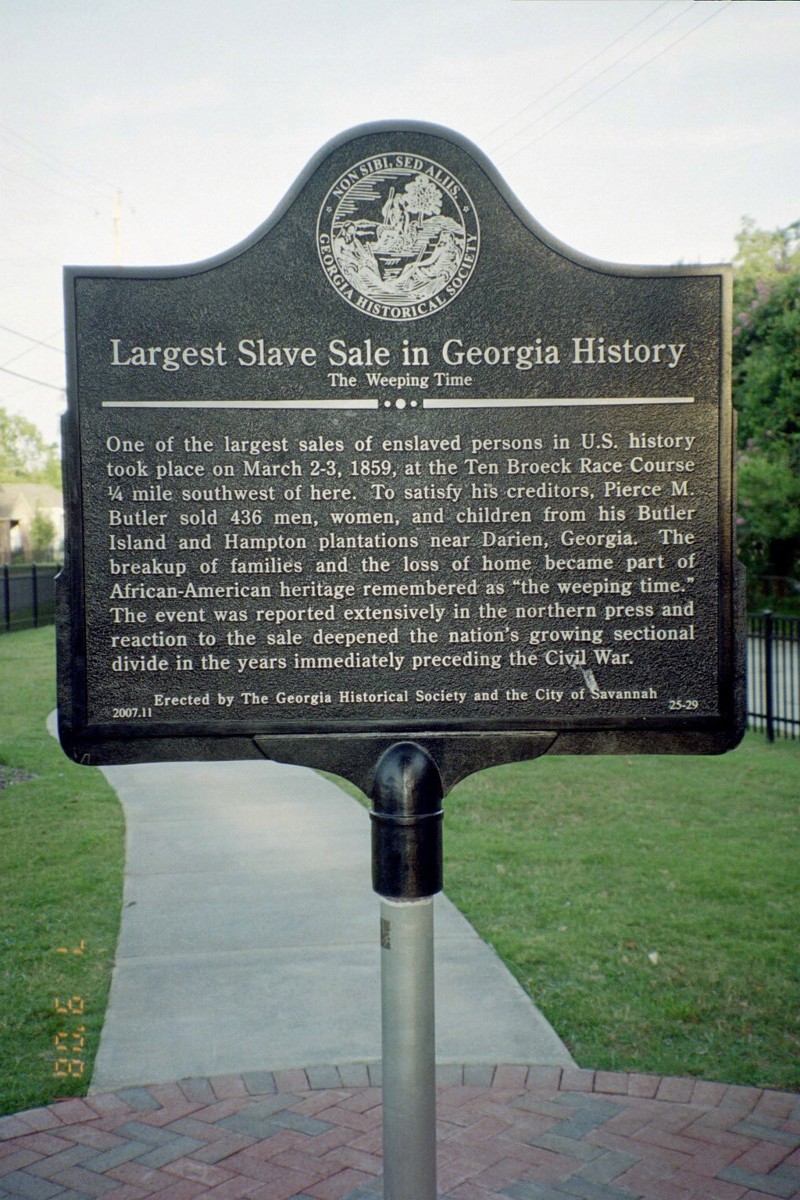

A marker commemorating “The Weeping Time” in West Savannah

A marker commemorating “The Weeping Time” in West Savannah

The only monument to this piece of state history is a steel marker a few miles outside Savannah, erected by the city and the Georgia Historical Society in 2007. The marker stands not at the actual site of the sale, which is now a lumber company next to an elementary school, but a quarter mile away in a tiny park. A person could visit Savannah’s main tourist district and never see the marker or hear the story behind it.

Kwesi DeGraft-Hanson, an Atlanta landscape architect and Emory University scholar, spent the last decade researching and mapping the sale site. Last fall he and two other researchers held a conference in Savannah to commemorate the sale and begin a near-impossible task of finding the descendants of those sold. The conference, in part, was sponsored through grants from the Georgia Humanities Council and the state General Assembly. DeGraff-Hanson is among a handful of Georgia scholars and historians who have pushed for greater state recognition of the Weeping Time.

“These places should be sacred to all of us,” said DeGraff-Hanson. “If I go to Auschwitz, I do not desecrate it. These places should be the same. The disrespect is to disregard this history.”

Stand in the middle of Savannah’s Johnson Square and look at all the surrounding banks. If there is one square in Savannah most appropriate for a monument to the Weeping Time it would be this one. Before the Civil War, the streets surrounding Johnson Square were the center of commerce that included slave brokerages, said Stan Deaton, senior historian for the Georgia Historical Society.

“This square played an important role in the economics of slavery; it financed it,” Deaton said. “Just like now, when you open a business you have to get capital to do it. So you would buy slaves in huge numbers using someone else’s capital. It’s like building a house; you would then sell it to people who paid cash or got it on credit. But the whole thing was propped up by banking institutions. And an enormous amount of capital was tied up in slave labor, which is what made it so valuable.”

The brokerage that arranged the sale of Butler’s slaves was along with this leafy common, one of Savannah’s oldest. Today no plaques signal which building housed brokerages, but local historians such as Vaughnette Goode-Walker, who give walking tours of the city, point them out easily.

The trustees of Butler’s estate arranged the sale with Joseph Bryan’s slave-trading house to settle Butler’s debts. Butler’s legacy in the trade was long. His grandfather, Pierce Butler, one of the nation’s Founding Fathers, wrote the Fugitive Slave Clause into the Constitution. In an interview with PBS, William Dusinberre, author of “Them Dark Days: Slavery in American Rice Swamps,” addressed the extraordinary wealth the Butlers had amassed and lost. He used that suit of armor as an example.

“He (John Butler) spent on that (costume) something like $400 or $500,” Dusinberre told PBS. “It cost him about $12 a year to feed and clothe a slave. So he was spending something like 40 times that amount of money for one appearance at a ball. … His brother (Pierce Butler) was wasting money on cards. … This young man, even though he was getting this huge income, was so irresponsible with his money he had to auction off all of his slaves.”

The auction was advertised for weeks in papers throughout the South and drew unprecedented attention. Mortimer Thomson, then a reporter for the New York Tribune, came to Savannah to cover the auction.

This rendering shows the footprint of the Ten Broeck Race Course, where the largest sale of human beings in the U.S. took place, superimposed over a satellite image of West Savannah.

Abolitionists saw it as an opportunity to “change hearts and show what was happening to enslaved people,” said Leslie Harris, an Emory University professor who has written extensively about the U.S. slave trade. “The connection between slaves and masters was an economic one. The fact remains that they were a property that was vulnerable to the economic whims and needs of their owners.”

Even now, Thomson’s account, written under the pen name Q.K. Philander Doesticks, is chilling in its depiction of what happened at the Ten Broeck Race Course grandstand. The sale began on March 2 in driving rain.

“The wind howled outside, and through the open side of the building the driving rain came pouring in; the bar downstairs ceased for a short time its brisk trade; the buyers lit fresh cigars, got ready their catalogs and pencils, and the first lot of human chattels was led up the stand,” Thomson wrote.

The constant rain and the tears of the slaves eventually led to the name, “the Weeping Time.”

In most cases, the slaves were sold as families, including a mother and her 15-day-old baby. Extended families and whatever community they had on the Butler plantations were destroyed. The 436 people sold over those two days went to plantations throughout the South. There’s little trace of what became of them.

DeGraff-Hanson became obsessed with finding the track after learning about the slave sale while doing research for his doctorate. He combed archives at Georgia State, Emory, and the University of Georgia for clues to the site. He finally found plat maps at the Georgia Historical Society and the Chatham County Department of Engineering from 1892 that showed where the old grandstand stood. From there the landscape architect used current aerial maps and superimposed the dimensions of the racetrack and grandstand onto the maps where both once were.

Today there are virtually no clues that the track was ever there.

Beyond a marker, “we need to commemorate these places,” said DeGraff-Hanson. “These men, women, boys, and girls should not go unrecognized.”

As we talk about how the South’s troubling history should be publicly remembered, the Weeping Time “has to be part of an honest reckoning with our past,” said Emory’s Harris. While we don’t know what happened to the descendants of the 436 sold, we do know this: in selling them, Pierce Butler made $303,850, just under $8.4 million in today’s dollars. He gave many of the slaves a dollar before they were taken off to points unknown. Afterward, Pierce Butler reportedly celebrated his windfall with bottles of champagne paid for by Bryan, the slave broker.