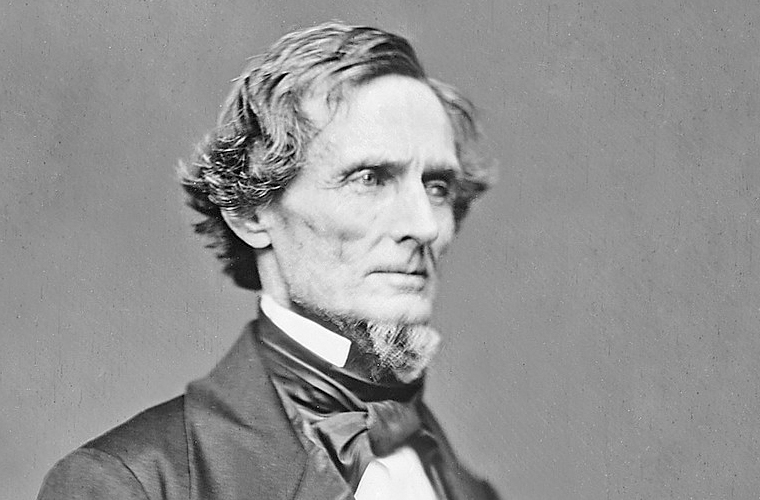

After a distinguished military career, Jefferson Davis served as a U.S. senator and as secretary of war under Franklin Pierce before his election as the president of the secessionist Confederate States of America. He was later indicted for treason, though never tried, and remained a symbol of Southern pride until his death in 1889. Jefferson Finis Davis was born on June 3, 1808, in Christian County, Kentucky (now called Fairview). One of 10 children born into a military family, his birth took place just 100 miles from and eight months earlier than President Abraham Lincoln’s. Davis’ father and uncles were soldiers in the American Revolutionary War, and three of his older brothers fought in the War of 1812.

Though born in Kentucky, Davis primarily grew up on the Rosemont Plantation near Woodville, Mississippi, eventually returning to Kentucky to attend boarding school in Bardstown. After completing his boarding school education, Davis enrolled at Jefferson College in Mississippi, later transferring to Transylvania University in Kentucky. In 1824, President James Monroe appointed Davis to a cadetship at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. One of Davis’ fellow cadets later described the burgeoning young leader as “distinguished in his corps for manly bearing and high-toned and lofty character.” In 1828, Davis graduated from West Point, the 23rd in his class.

Upon graduating from West Point, Davis was assigned to the post of second lieutenant of the First Infantry. From 1828 to 1833, he carried out his first active service with the U.S. Army. Davis fought with his regiment in the Blackhawk War of 1831, during which they captured Chief Blackhawk himself. The Indian chief was placed under Davis’ care, with Davis winning Blackhawk over through his kind treatment of the prisoner.

In March 1833, Davis was promoted to first lieutenant and transferred to the First Dragoons, a newly formed regiment. He also served as the unit’s staff officer. Until the summer of 1835, Davis continued his service on the battlefield against Indian tribes, including the Comanche and Pawnees. In June 1835, Davis married his commanding officer’s daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor. Because his commanding officer, none other than future president Zachary Taylor, was opposed to the marriage, Davis abruptly resigned from his military post to take up civic duties prior to the wedding. Sadly, Sarah died of malaria just a few months later, in September 1835.

After leaving the military, Davis became a cotton farmer while preparing for a career in politics as a Democrat. In 1843, he participated in the gubernatorial campaign and served as a delegate at the Democratic National Convention. His powerful speeches there placed him in high demand. One year later, he became an elector for Polk and Dallas, taking the stance of state protection against federal interference and supporting Texas’ annexation in the process.

In December 1845, Davis won an election to the U.S. House of Representatives and claimed a seat in Congress, which caused him to gain more public attention. Additionally, he remarried, this time to a woman named Varina Howell. The marriage helped further forge his connection with Mississippi planters, as Varina’s family was of that class. As a congressman, Davis was known for his passionate and charismatic speeches, and he quickly became actively involved in debates about Texas, Oregon, and tariffs. Davis’ congressional accomplishments include orchestrating the conversion of forts into military training schools. Throughout his congressional term, his support of states’ rights remained unwavering.

In June 1846, Jefferson Davis resigned from his position in Congress to lead the First Regiment of the Mississippi Riflemen in the Mexican-American War. He held the rank of colonel under his former father-in-law, General Taylor. During the Mexican-American War, Davis fought in the Battles of Monterrey and Buena Vista, in 1846 and 1847, respectively. At the Battle of Monterrey, he led his men to victory in an assault at Fort Teneria. He was injured at the Battle of Buena Vista when he blocked a charge of Mexican swords — an incident that earned him nationwide acclaim. So impressed was General Taylor that he admitted he had formerly misjudged Davis’ character. “My daughter, the sir, was a better judge of man than I was,” Taylor reportedly conceded.

In 1847, following Davis’ heroic feat, Taylor appointed him U.S. senator from Mississippi — a seat that had opened as a result of Senator Jesse Speight’s death. After serving the rest of Speight’s term, from December to January of 1847, Davis was re-elected for an additional term. As a senator, Davis advocated for slavery and states’ rights and opposed the admission of California to the Union as a free state — such a hot-button issue at the time that members of the House of Representatives sometimes broke into fistfights. Davis held his Senate seat until 1851 and went on to run for the Mississippi governorship, but lost the election.

Explaining the way his position on the Union had evolved during his time in the Senate, Davis once stated, “My devotion to the Union of our fathers had been so often and so publicly declared; I had on the floor of the Senate so defiantly challenged any question of my fidelity to it; my services, civil and military, had now extended through so long a period and were so generally known, that I felt quite assured that no whisperings of envy or ill-will could lead the people of Mississippi to believe that I had dishonored their trust by using the power they had conferred on me to destroy the government to which I was accredited. Then, as afterward, I regarded the separation of the states as a great, though not the greater evil.”

In 1853, Davis was appointed secretary of war by President Pierce. He served in that position until 1857 when he returned to the Senate. Although opposed to secession, while back in the Senate, he continued to defend the rights of Southern slave states. Davis remained in the Senate until January 1861, resigning when Mississippi left the Union. In conjunction with the formation of the Confederacy, Davis was named president of the Confederate States of America on February 18, 1861. On May 10, 1865, he was captured by Union forces near Irwinville, Georgia, and charged with treason. Davis was imprisoned at Fort Monroe in Virginia from May 22, 1865, to May 13, 1867, before being released on bail paid partly by abolitionist Horace Greeley.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Following his term as president of the Confederacy, Davis traveled overseas on business. He was offered a job as president of what became Texas A&M University but declined. He was also urged to make another run for the Senate, though he would have required approval from both the Senate and the House to hold office again, under the terms of the 14th Amendment.

In 1881, he wrote The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government in an effort to defend his political stance. Davis lived out his retirement years at an estate called Beauvoir in Mississippi. Around 1 a.m. on December 6, 1889, Davis died of acute bronchitis in New Orleans, Louisiana. His body was temporarily interred at New Orleans’s Metairie Cemetery. It was later relocated to a specially constructed memorial at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

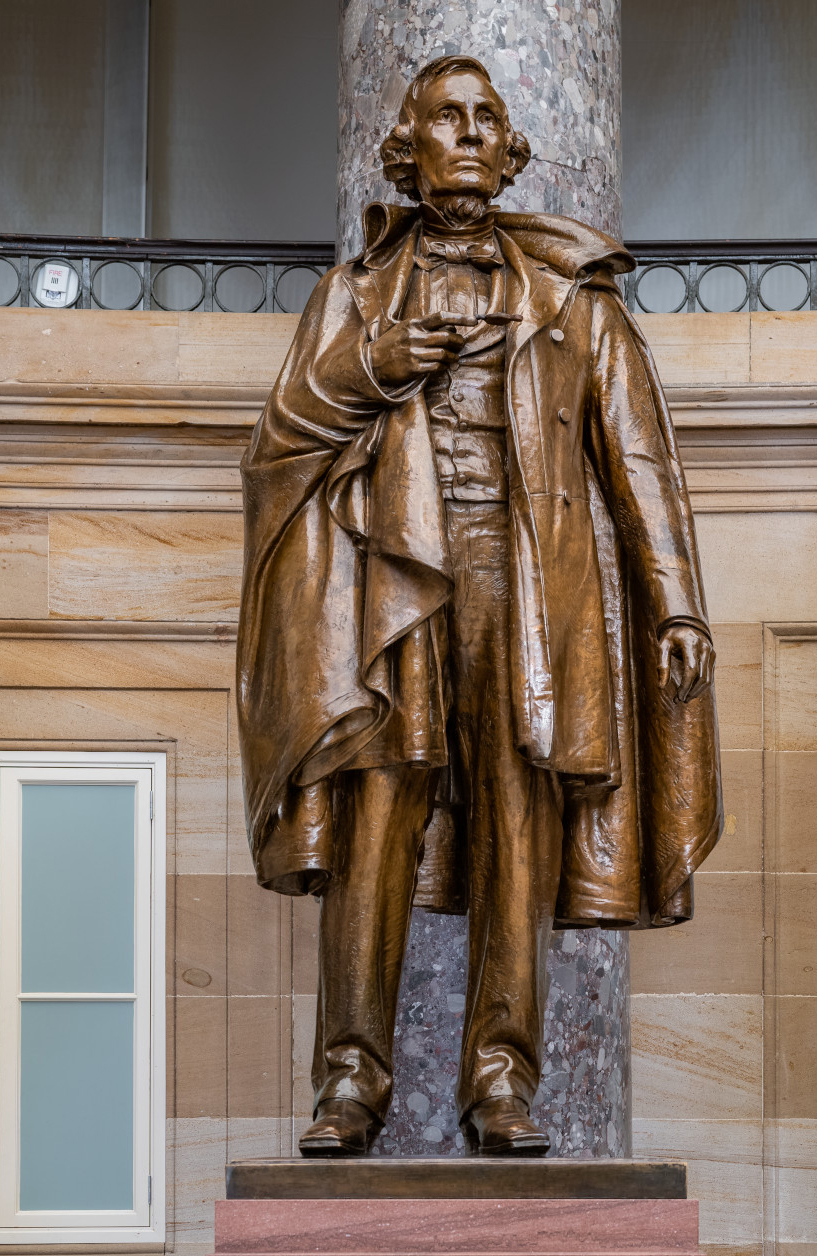

A powerful and influential statesman, Davis left behind a legacy that is similar in some ways to other U.S. presidents. His birthday is celebrated in several Southern states, and his presidential library opened in Mississippi in 1998. In 1978, his U.S. citizenship was posthumously restored. As with other Confederate leaders, public monuments to Davis have generated considerable controversy in recent years. In December 2017, following a heated legal battle, residents of Memphis, Tennessee, managed to have a statue of Davis removed from a park.

In the summer of 2017, Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney announced the formation of a commission to recommend “how to best tell the real story” of the Confederate-era statues on tourist-packed Monument Avenue. In a report released the following July, the commission suggested the removal of a 111-year-old bronze statue of Davis, a move that would require legal action to change state law. Other recommendations included designing more elaborate exhibits to provide context for the statues of Generals Robert Lee and Stonewall Jackson, as well as creating a memorial to slaves and to soldiers of the United States Colored Troops who fought in the Civil War.