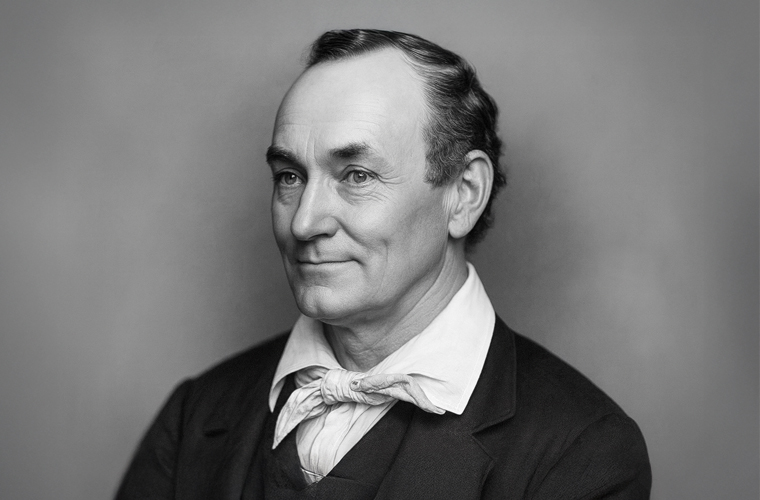

Thomas Dartmouth Rice, born on May 20, 1808, in New York City’s Lower East Side, was a product of the working-class theater scene in the early 19th century. Before achieving fame, Rice was a journeyman actor, playwright, and stagehand, performing in small theaters and traveling troupes. His early career involved a mix of comedic roles and low-budget productions, but he struggled to stand out in the competitive entertainment landscape of the time. It was during his travels, particularly in the American South, that Rice encountered the inspiration for what would become his most infamous creation: the “Jim Crow” character.

The origin story of “Jim Crow” is often tied to an anecdote from around 1828, when Rice, while in Louisville, Kentucky, reportedly observed an enslaved African American man (sometimes identified as an elderly stablehand) performing a distinctive song and dance. Rice adapted this into a theatrical routine called “Jump Jim Crow,” which he performed in blackface—a practice where white performers used burnt cork, greasepaint, or shoe polish to darken their skin and exaggerate facial features to caricature Black people. The act featured exaggerated gestures, tattered clothing, and a mock dialect that stereotyped African Americans as ignorant and subservient. While the veracity of this origin story is debated, it reflects the exploitative nature of minstrelsy, where white performers appropriated and distorted Black culture for profit.

Rice’s “Jump Jim Crow” routine debuted in the early 1830s and became an instant hit, transforming him into one of the most famous entertainers of his era. His performances, marked by physical comedy, catchy tunes, and racist humor, captivated white audiences in cities like New York, Philadelphia, and even London, where he toured in 1836. The popularity of the “Jim Crow” character not only elevated Rice’s career but also helped codify minstrelsy as a distinct and widely popular theatrical genre.

Minstrelsy, as popularized by Rice and his contemporaries, was a uniquely American form of entertainment that emerged in the 1820s and reached its peak in the mid-19th century. Minstrel shows typically featured white performers in blackface performing skits, songs, and dances that mocked African Americans, often portraying them as lazy, foolish, or overly jovial. These performances were structured in three acts: an opening with comedic banter and songs, a middle “olio” section with variety acts, and a final act often featuring a plantation-themed skit. The shows appealed to white audiences across class lines, from urban working-class theatergoers to middle-class families, by reinforcing racial hierarchies and providing a sense of cultural superiority during a time of social and economic upheaval.

Rice’s “Jim Crow” character was one of the earliest and most influential archetypes in minstrelsy, alongside other stock characters like the “Zip Coon” (a dandyish urban Black caricature) and the “Mammy” (a nurturing but subservient Black woman). His performances helped standardize the blackface aesthetic, which included exaggerated red lips, widened eyes, and tattered costumes meant to evoke plantation life. The “Jump Jim Crow” song itself, with its repetitive melody and lyrics like “Wheel about and turn about and do just so Every time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow,” became a cultural phenomenon, spawning countless imitations and adaptations.

Minstrelsy’s popularity extended beyond Rice, giving rise to professional troupes like the Virginia Minstrels and Christy’s Minstrels in the 1840s. These groups formalized the genre, but Rice’s role as a pioneer was undeniable. His success demonstrated the commercial potential of blackface performance, paving the way for a flood of imitators who further entrenched racist stereotypes in American popular culture.

The cultural impact of Rice’s performances and minstrelsy as a whole was profound and deeply harmful. By presenting caricatured depictions of African Americans, minstrel shows reinforced negative stereotypes that justified slavery, segregation, and racial discrimination. These performances portrayed Black people as inherently inferior, reducing their humanity to a series of comedic tropes. For white audiences, minstrelsy provided a distorted lens through which to view African Americans, shaping perceptions that persisted long after the shows faded from prominence.

The term “Jim Crow,” originally popularized by Rice’s character, took on a broader and more insidious meaning in the post-Civil War era. By the late 19th century, “Jim Crow” became synonymous with the system of legalized racial segregation in the United States, particularly in the South, where laws enforced separate facilities for Black and white people in schools, transportation, and public spaces. While Rice did not directly create these laws, his role in popularizing the term and its associated imagery contributed to a cultural environment that normalized racial hierarchy.

Minstrelsy also had a complex relationship with African American culture. While it exploited and mocked Black traditions, it inadvertently introduced elements of Black music, dance, and humor to wider audiences. For example, the banjo, an instrument with African origins, became a staple of minstrel performances, though its cultural significance was often stripped away or misrepresented. Some African American performers later entered the minstrel circuit, particularly after the Civil War, but they were forced to conform to the same degrading stereotypes, often performing in blackface themselves to meet audience expectations.

To understand Rice’s performances, it’s essential to place them within the historical context of the early 19th century. The United States was a deeply divided nation, grappling with the moral and economic tensions of slavery. Minstrelsy emerged during a period of rapid urbanization, immigration, and class conflict, particularly in Northern cities where white working-class audiences sought entertainment that affirmed their social status. By mocking African Americans, minstrel shows allowed white audiences—many of whom were immigrants or working-class laborers—to distance themselves from the lowest rungs of the social ladder.

At the time, Rice’s performances were not widely criticized for their racism, as such views were normalized in white society. However, even in the 19th century, some abolitionists and African American intellectuals condemned blackface and minstrelsy for their dehumanizing portrayals. Frederick Douglass, in an 1848 editorial in his newspaper The North Star, described blackface performers as “the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow-citizens.” Douglass’s critique highlights the exploitative nature of minstrelsy and its role in perpetuating systemic racism.

Thomas Dartmouth Rice’s legacy is a complicated and uncomfortable one. While he was a significant figure in the history of American theater, his work is now recognized as a cornerstone of a deeply racist tradition. Minstrelsy’s influence extended far beyond the 19th century, shaping early film, vaudeville, and even modern entertainment. The blackface aesthetic persisted in Hollywood films like The Jazz Singer (1927) and Birth of a Nation (1915), and traces of minstrel stereotypes can be seen in later media portrayals of African Americans.

Today, Rice and the minstrel tradition are studied as examples of how popular culture can perpetuate harmful ideologies. The history of blackface is a critical lens through which scholars and activists examine the roots of racial stereotypes and their enduring impact. In recent years, revelations about the use of blackface in historical and even modern contexts—such as by politicians or entertainers—have sparked renewed debates about its legacy and the need for accountability.

The term “Jim Crow” remains a powerful reminder of the systemic racism that defined much of American history. Discussions about Rice’s performances often serve as a starting point for exploring broader issues of representation, cultural appropriation, and the responsibility of artists to challenge rather than reinforce harmful stereotypes. Contemporary efforts to address this legacy include removing offensive imagery from media, renaming institutions associated with “Jim Crow,” and amplifying authentic Black voices in entertainment and culture.

Thomas Dartmouth Rice, through his creation of the “Jim Crow” character, played a pivotal role in shaping American popular culture, but his legacy is inseparable from the racism embedded in his work. His performances, while innovative for their time, contributed to a cultural framework that dehumanized African Americans and justified their oppression. Understanding Rice’s impact requires acknowledging both his historical significance and the harm caused by his art. By studying this history, we gain insight into the power of performance to shape societal attitudes and the ongoing need to confront and dismantle the legacies of racism in all its forms.