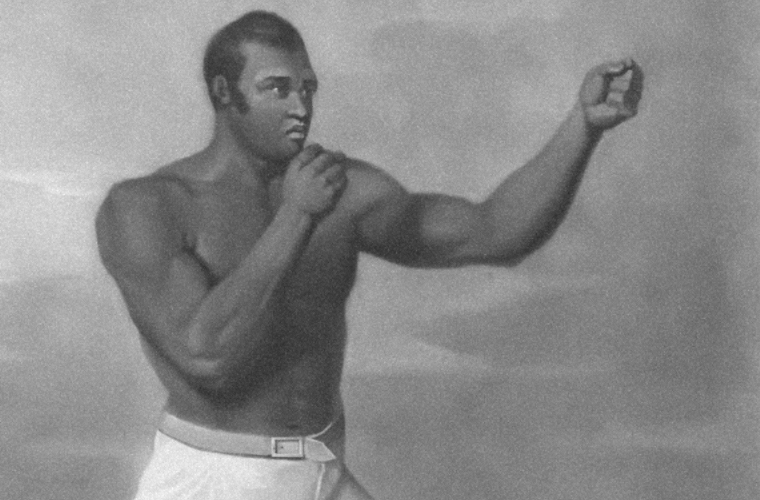

A new TG4 documentary tells of Tom Molineaux, who boxed his way to freedom from slavery before he died destitute in Ireland, writes Richard Fitzpatrick

In the grassy, hilltop graveyard in Mervue, close to Galway City, lie the remains of America’s first boxing star. His name was Tom Molineaux. He was buried there in 1818. His story is remarkable.

“There were just a few people who knew about him, really,” says Des Kilbane, co-director of Crossing the Black Atlantic, a documentary about the life of Molineaux. “Even in Virginia, where Molineaux grew up, when we were over there filming, only one historian heard about him. That was about it. More people knew about him in Galway than in Virginia.”

Kilbane had heard about Molineaux in despatches, while filming a previous boxing documentary, and was directed to the Galway bookseller, Tom Kenny, to find out more.

“I went to Tom Kenny and he said, ‘Oh, that’s the lad that’s buried up in Mervue.’ Then, he produced this three-volume book, called Pugilistica. The books were really old, well over 100 years old, and very rare. They were a history of British boxing in the nineteenth century. He showed me the chapter on Tom Molineaux. It gave a lot of information.

“I could see this really is a West of Ireland story, a local story with national and international aspects to it, which tied in the Galway families that were involved in the slave trade in the Caribbean. We took it from there.”

Molineaux was born on a plantation farm in Virginia, the tobacco capital of the world, in 1784. During the American War of Independence, when the colonies rose up against British rule, his father, Zachery, fought alongside his slave owner, the master of the Molineaux plantation farm.

Tom Molineaux took his surname from the plantation owner, as was practice for a child born into slavery. His father’s heroics in the War of Independence accorded his son a little status growing up, so young Tom became tight with the plantation owner’s son, Algernon Molineaux.

Molineaux earned his freedom after winning a boxing match against a slave from a rival plantation. There was a $400 purse on the fight, which was a huge sum. Molineaux drifted towards New York and eventually set sail for England, the center of the boxing universe, in 1809.

In 1810, he fought three boxing fights, winning the first two (one against a guy called ‘Tom Tough’), before he landed his money shot — about against Tom Cribb, the reigning British boxing champ. It was effectively a world-title fight, in an outdoors ring 30 miles outside London.

It was a bare-knuckle fight, as was customary. It was extraordinarily bloody. The two men battered each other so badly — a black man and a white man — that spectators were unable to tell them apart.

According to the boxing writers who covered the fight, including a legendary scribe, Pierce Egan, Molineaux was done out of it by foul means. Egan wrote: “it was the most dreadful affront to British sportsmanship ever witnessed”.

While Molineaux had Cribb in a headlock, fans stormed the ring and broke some of Molineaux’s fingers, so Cribb could release himself. A re-match was fixed, but Molineaux was easily beaten in it. He was a sucker for distractions out of the ring — chiefly drinking and womanizing — so he was out of shape.

His star went on the wane on the British boxing scene. In 1815, he moved to Ireland, where there was also a vibrant boxing scene, although the purses he earned were smaller. He mainly fought in fairs and exhibitions. He challenged Dan Donnelly, a renowned Dublin fighter, but Donnelly refused to take him on, maintaining he wouldn’t fight “a conquered man or a black man”.

“Molineaux accused Donnelly of being a racist, and maybe he was, but Molineaux wasn’t at his best by then,” says Kilbane. “There would have been no great gain for

Donnelly’s reputation to beat a man that was on the way out. Molineaux was 32. Donnelly took one look at him and said, ‘I’m not fighting you.’

“In Ireland, at the time, even though there were Irish planters involved in the slave trade — particularly out of Galway, Cork, Limerick, Dublin, and Belfast — Dublin had its black man-servants, and they were treated decently enough. In the early 1800s, it was a status symbol for the middle classes to have one.”

Molineaux slipped further and further down the social scale. His body withered from drinking and TB. His falling weight took from his boxing prowess.

He died in 1818, his last year or two spent in Galway, where he fought in Eyre Square and other market squares, alongside competing Sunday attractions like badger-baiting and cock-fighting.

Almost a century later, his career was summed up in that old boxing book, Pugilistica, which was published in 1905: “From Scotland, Molineaux went on a sparring tour to Ireland. At the later end of the year 1817, he was traveling over the northern parts of that country, teaching the stick-fighting natives the use of their fists… Molineaux was illiterate and ostentatious, but good-tempered, liberal, and generous to a fault.

Fond of gay clothes, gay life, and amorous to the extreme, he deluded himself with the idea that his strength of constitution was proof against excesses.”

George Washington — boxing coach?

It seems George Washington — one of the founding fathers of the United States and its first president — was a useful boxer. He had the build — he stood at 6ft 2in with a long reach, and according to Sports Illustrated he was also an accomplished wrestler who was “a master of the British style known as collar and elbow”.