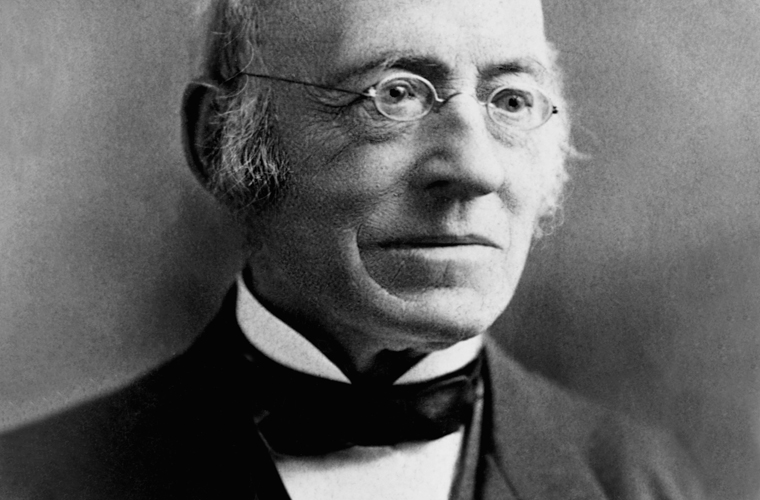

William Lloyd Garrison was an American journalistic crusader who helped lead the successful abolitionist campaign against slavery in the United States. William Lloyd Garrison was born December 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Massachusetts. In 1830 he started an abolitionist paper, The Liberator. In 1832 he helped form the New England Antislavery Society. When the Civil War broke out, he continued to blast the Constitution as a pro-slavery document. When the civil war ended, he, at last, saw the abolition of slavery.

He died May 24, 1879, in New York City

Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was born the son of a merchant sailor in Newburyport, Massachusetts on December 10, 1805. When Garrison was only three years old, his father Abijah abandoned the family. Garrison’s mother, a devout Baptist named Frances Maria, struggled to raise Garrison and his siblings in poverty. As a child, Garrison lived with a Baptist deacon for a time, where he received a rudimentary education. In 1814, he reunited with his mother and took an apprenticeship as a shoemaker, but the work proved too physically demanding for the young boy. A short stint at cabinetmaking was equally unsuccessful. In 1818, when Garrison was 13 years old, he was appointed to a seven-year apprenticeship as a writer and editor under Ephraim W. Allen, the editor of the Newburyport Herald. It was during this apprenticeship that Garrison would find his true calling. Through Garrison’s various newspaper jobs, he acquired the skills to run his own newspaper. After he finished his apprenticeship in 1826, when he was 20 years old, Garrison borrowed money from his former employer and purchased The Newburyport Essex Courant. Garrison renamed the paper the Newburyport Free Press and used it as a political instrument for expressing the sentiments of the old Federalist Party. In it, he would also publish John Greenleaf Whittier’s early poems. The two forged a friendship that would last a lifetime. Unfortunately, the Newburyport Free Press lacked similar staying power. Within six months, the Free Press went under due to subscribers’ objections to its staunch Federalist viewpoint.

When the Free Press folded in 1828, Garrison moved to Boston, where he landed a job as a journeyman printer and editor for the National Philanthropist, a newspaper dedicated to temperance andreformn

1828, while working for the National Philanthropist, Garrison took a meeting with Benjamin Lundy. The antislavery editor of the Genius of Emancipation brought the cause of abolition to Garrison’s attention. When Lundy offered Garrison an editor’s position at Genius of Emancipation in Vermont, Garrison eagerly accepted. The job marked Garrison’s initiation into the Abolitionist movement. By the time he was 25 years old, Garrison had joined the American Colonization Society. The society held the view that blacks should move to the west coast of Africa. Garrison at first believed that the society’s goal was to promote blacks’ freedom and well being. But Garrison grew disillusioned when he soon realized that their true objective was to minimize the number of free slaves in the United States. It became clear to Garrison that this strategy only served to further support the mechanism of slavery. In 1830 Garrison broke away from the American Colonization Society and started his own abolitionist paper, calling it The Liberator. As published in its first issue, The Liberator’s motto read, “Our country is the world—our countrymen are mankind.” The Liberator was responsible for initially building Garrison’s reputation as an abolitionist.

Garrison soon realized that the abolitionist movement needed to be better organized. In 1832 he helped form the New England Antislavery Society. After taking a short trip to England in 1833, Garrison founded the American Antislavery Society, a national organization dedicated to achieving abolition. However, Garrison’s unwillingness to take political action (rather than simply write or speak about the cause of abolition) caused many of his fellow abolitionist supporters to gradually desert the pacifist. Inadvertently, Garrison had created a fracture among members of the American Antislavery Society. By 1840, defectors formed their own rival organization, called the American Foreign and Antislavery Society.

In 1841, an even greater schism existed among members of the abolitionist movement. While many abolitionists were pro-Union, Garrison, who viewed the Constitution as pro-slavery, believed that the Union should be dissolved. He argued that Free states and slave states should, in fact, be made separate. Garrison was vehemently against the annexation of Texas and strongly objected to the Mexican American War. In August of 1847, Garrison and former slave Frederick Douglass made a series of 40 anti-Union speeches in the Alleghenies.

1854 proved a pivotal year in the Abolition Movement. The Kansas-Nebraska Act established the Kansas and Nebraska territories and repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had regulated the extension of slavery for the prior 30 years. Settlers in those areas where allowed to choose through Popular Sovereignty whether or not they would allow slavery there. The plan, which Garrison considered “a hollow bargain for the North,” backfired when slavery supporters and abolitionists alike rushed Kansas so they could vote on the fate of slavery there. Hostilities led to government corruption and violence. The events of the 1857 Dred Scott Decision further increased tensions among pro and anti-slavery advocates, as it established that Congress was powerless to ban slavery in the federal territories. Not only were blacks not protected by the Constitution, but according to it, they could never become U.S. citizens.

In 1861, as the American Civil War broke out, Garrison continued to criticize the U.S. Constitution in The Liberator, a process of resistance that Garrison had now practiced for nearly 20 years. Understandably, some found it surprising when the pacifist also used his journalism to support Abraham Lincoln and his war policies, even prior to the Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862. When the Civil War came to a close in 1865, Garrison, at last, saw his dream come to fruition: With the 13th Amendment, slavery was outlawed throughout the United States—in both the North and South.